![]()

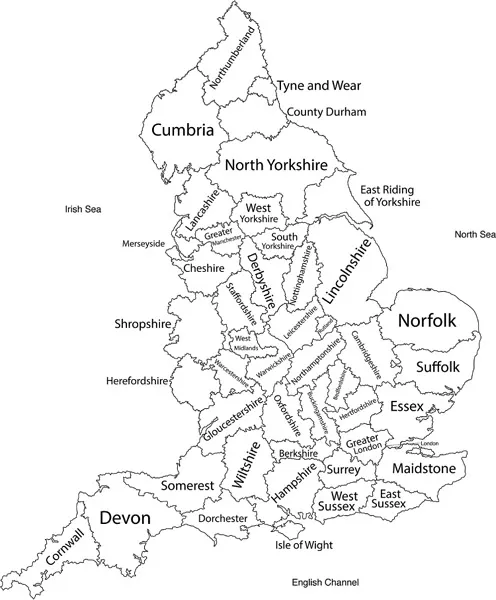

Figure 1.1 Map of England. Used under license from Shutterstock.com.

1 How the Other Half Lives

Rural Women Encounter England’s Land Rights Revolution

During the sixteenth century, most rural women and men lived in commons-based, male-led village communities that legitimized male land claims, but also guaranteed women’s rights of access to a kitchen garden. In the centuries to come, they experienced an irreversible land rights revolution (enclosure) that privatized common lands, compelled them to abandon their farms, gardens, and communities, and compete as individuals in a labor market. Enclosure reformers and contemporary theorists claimed—wrongly—that radical tenure transformation was required because peasants were utterly backward and subjugated by their “medieval” communities. Laws of coverture eliminated women’s rights to land ownership. In the 1980s, researchers documented significant evidence of rural innovation that occurred before enclosure. Rural resistance—with women frequently in the forefront—ensured that the enclosure process would take 300 years to complete. The economic and labor history of rural women before or during enclosure has yet to be written.

Throughout English history, rural men and women enjoyed many unearned advantages—among them, relatively fertile land, a temperate climate, and freedom from foreign invasion (in contrast to Russia and Kenya). As we shall see, reformers frequently attributed their economic success to the wisdom of their policies and programs; they did not place a great deal of emphasis on England’s extraordinary natural and historical advantages over many other nations. In our cases, economic success and failure were not simply a matter of making rational economic choices. In contrast to our other cases, the English were not confronted by severe ecological constraints, repeated foreign invasions, or colonial conquest.

On the Eve

During the seventeenth century, the acceleration of tenure transformations imposed from above forced millions of rural men and women to remake their economic and noneconomic lives. However, when our England story begins, most of England’s population lived as tenants on estates created over the centuries by kings, nobles, and clergy who appropriated their land and awarded themselves extraordinary rights to control and manage the labor of the rural men and women who were living on it. From the outset, their efforts were contested by peasants mobilized for resistance by their village rural community institutions. During the seventeenth century, male-run village councils (juries) acknowledged multiple, overlapping, long- and short-term land claims, universal land access for men and for women, and common lands open to all. Some of these land arrangements were uniquely English, but as we shall see, many appear in our other cases.

Although Englishmen of privilege possessed immense powers to constrain and control the activity of their social inferiors, it is significant that before enclosure they nevertheless acknowledged peasant land claims based on occupancy and the investment of labor, as well as principles of universal land access for all members of the community. Tenants were obliged to pay rent to landlords in exchange for access to designated amounts of farmland, woods, and pasture held in common. While land legally belonged to the estate-owner, it was property of a peculiar sort—available to local commoners but not to the general public. Within this framework, peasant communities acknowledged temporary, long-term, permanent, individual, household, and communal tenure arrangements. Distinctions between rights of ownership and use were neither fixed nor permanent.

Where Are the Women?

For centuries, the gender-biased assumptions of contemporary data gatherers severely limited our understanding of land rights revolution. By creating rural databases that omitted the female population, they left future researchers with a historical record that was sorely deficient and demographically unbalanced. Despite the excellent efforts of England scholars over the past three decades, a highly gendered, male-centered database remains a barrier to the creation of a more inclusive (and more accurate) historical narrative. The empirical gaps that complicate research on women’s labor history are far greater for England than for our other cases. Although research obstacles of this sort plague many scholars who seek to establish the specifics of women’s economic decision-making on garden plots and commons, or the rules governing how garden or commons produce was appropriated or sold, the English database may well represent the greatest research challenge.1

This study suggests that filling in some of these data gaps is crucial not only to understanding enclosure, but also to our grasp of core features of economic development past and present. Over 20 years ago, Anne Lawrence called for a reversal in conventional research priorities, calling for a greater emphasis on what rural women were able to do, rather than the more familiar topic of what they were prevented from doing.2 To the extent that evidence permits, the research presented here builds on the ground-breaking work of contemporary scholars like Jane Whittle and Joanne Bailey, and Andy Wood’s exemplary model of broadly inclusive rural history. To the time-honored assumption that men were England’s primary economic actors, Bailey asks us to consider the evidence that the material survival of husbands was probably as dependent on women as their wives were dependent on them, particularly in the areas of domestic economy, household management, and child care.3 Women were the household’s primary food producers. Nevertheless, according to Nicola Verdon, writing in 2003, “a holistic and systematic analysis of the whole range of tasks undertaken by peasant women is not [yet] possible.”4 In 2014, historian Jane Whittle observed: “Scattered research on women’s contribution to agriculture needs to be expanded into something a great deal more systematic.”5

The Complexity and Power of Rural Communities

Long before the seventeenth century, village communities were responsible for enforcing the economic and noneconomic demands made by landlords, clergy, and monarchs who appropriated peasant land. At the same time, they were among the few institutions capable of re-interpreting, adjusting, and mitigating these impositions. In practice, landowners rarely intervened directly in day-to-day farming practices on their estates. On a village level, male village councils (juries) set the economic and noneconomic rules of the village game. They apportioned land to adult male household heads, established the size and location of women’s gardens, and regulated access to cultivated fields, pasture lands, and common lands. Although men dominated English rural society, it is remarkable that all-male juries nevertheless guaranteed women exclusive rights to use kitchen gardens that ranged up to 10 acres in size. Due to the scarcity of data and prevalence of negative assumptions about peasant communities, we know relatively little about their role as local guarantors of women’s land access. It is equally difficult to know the specifics of women’s labor or economic acumen in these or other venues. As a consequence, it is not yet possible to make a grounded empirical comparison between the economic history of enclosure-era Englishwomen and the histories of their rural counterparts elsewhere.

In seventeenth-century England, community rules for member land use were flexible—at times, long-term, short-term, or temporary—but rarely permanent. Before enclosure, juries determined the right of member households to own and cultivate specific land allotments, and set the rules for village use of commonly held resources. Like their counterparts in Imperial Russia, they periodically readjusted allotment size in keeping with demographic changes in the community, natural catastrophe, and other unforeseen circumstances.6 In both cases, village councils organized strip cultivation—a risk-spreading practice devised to ensure that no household monopolized the best land.7 Typically, they divided the communities’ arable land into scattered strips of land, designating a certain number of strips as an allotment to each household. This farming method required a common routine of sowing, reaping, and harvesting.

At planting time, one might see long lines of men, women, and children from one household at work on a land-strip alongside another household engaged in precisely the same kind of labor. Although this was clearly an inefficient mode of cultivation, the virtues of efficiency frequently paled in comparison with the economic insecurity experienced by peasants who lived at the edge of subsistence. Because few rural households regularly produced a surplus, peasants were in general unwilling to assume that they could survive independently of one another. Before enclosure, peasants in possession of community-guaranteed land allotments would have found it difficult to comprehend Jurist William Blackstone’s eighteenth-century claim that land ownership was “that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the rights of any other individual in the universe.”8 To Blackstone, multi-tenured land claims were not property; they were primitive chaos.

In many parts of rural England (and in Imperial Russia), an open-field system governed the rhythms of the agricultural year. After harvest, juries organized the practice of “throwing open” cultivated land to all members of the community. During this period, household allotments became common land. After harvest, women—led by a “Queen of the Gleaners”—organized the gathering of grain that remained in the fields. In some parts of the country, gleaning was a major source of a woman’s contribution to the household budget. Particularly in times of scarcity, it provided a vital safety net for widow-headed households.9

Open-field communities were neither collectivist nor egalitarian. They guaranteed individual and separable rights to personal property to both men and women. As in many other historical settings, some households—through hard work, luck, corrupt dealings, or by chance—became far wealthier than their neighbors. The open-field system was far from universal, and was virtually unknown in East Anglia, Kent, and many parts of the north and west of England. Nevertheless, it was a significan...