![]()

p.21

1 The features of the bank structural problem and its structural attribute

The bank structural problem is at the centre of current world wide regulatory reform. For example, the EC adopted the BSR proposal for structural measures in January 2014. Other major economies are all making similar progress, including the US, the UK and Germany.1 The TBTF bank structural problem refers to the ineffectiveness in the supervision and regulation of banks with the universal banking model.2 The co-existence of various activities within the same entity acted as a destabilising factor in the run up to the GFC. The bank structural problem is basically one of the major reasons why the banking sector has become too complex to manage, to supervise, and to fail. Thus, the reform to deal with the TBTF bank structural problem is a significant and indispensable part of the current post-crisis comprehensive financial reform.3

1 Bank structural problem in the EU

The structural problem came about within the context of global lax monetary policy, financial liberalisation, and the encouragement of financial innovation both from policy-makers and the financial industry.4 Financial innovation was at the forefront of the global financial liberalisation; it reflected the inception and key features of the TBTF structural problem.

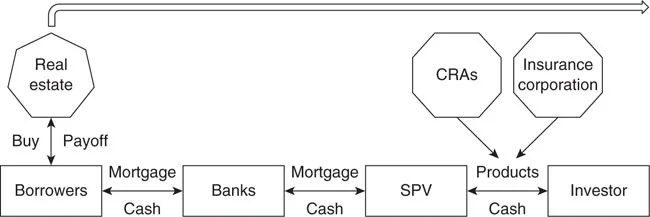

The structural debt securities represented the forefront of the financial innovation and securitisation. With the rise of real estate prices, mortgages were extended to every potential borrower irrespective of their creditworthiness, credit history, and default risk. The reason was that the innovation of the ‘originate-to-distribute model’ was designed to transfer the default risk away from the banks.5 The model made it possible for the banks to sell all the debts to a packager who would act as an originator and repackage them into some structural financial products, such as Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS), Collateral Debt Obligations (CDOs), through Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV).6 Then, by selling these structural debt securities to other investors, the risk could be transferred to some institutional investors, such as hedge funds and pension funds. Of course, to increase the creditworthiness of these structural securities, Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) were also involved to provide marketable ratings. To further diversify the risk, the insurance company designed various credit derivatives, such as Credit Default Swaps (CDS), to ensure the investors of the safety of these products. By these operations, it seemed that the risks had been transferred away from the banks. But due to the interconnectedness of the financial industry, such as interbank wholesale financing, the risks were only spread to more entities, but never addressed.7 On the contrary, the misleading illusion of risk being transferred away only encouraged all the entities in the above product chain to be less meticulous and more inclined to engage in risk-taking. Riding on the wave of the economies of scope and scale, the banks became larger and larger and reached the scale of systemically important institutions.8

p.22

On the negative side, the above product chain not only increased the overall leverage of the financial system, but also intensified the risk-taking inclination, the interconnectedness, and homogeneity of the banking sector. It brought about the financial instability of the industry. It was really a debilitating factor to the industry in the long run (Figure 1.1).9

p.23

In the end, the misaligned interests in the above product chain fuelled the economic boom to its extreme, and it went bust starting with the fall of Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns in 2008. Due to the interconnectedness and homogeneity of banks, the failure of a few entities instantly contaminated all relevant entities in the product chain and the industry as a whole.

As a matter of fact, being one of the most important regions where the banking industry loomed so large, the EU was the first victim due to the contagion effect of the US subprime mortgage crisis.10 Afterwards, the deteriorating market situation forced the EU to bail out ailing banks, which consequently triggered the downgrade of the sovereign debts and thereafter the sovereign debt crisis. Finally, market confidence further deteriorated into the overall economic crisis.11

2 The ‘three gorges’ metaphor

The analogy of the ‘three gorges’ battle on the Yangtze River in the three kingdoms dynasty might shed some light on how to tackle bank structural reform in the EU.12 To a certain extent, the implied ‘mechanical theory’ and ‘let the ship sink wisdom’ in the story could be applied to financial regulation.13

This was a landmark battle in history because it was a battle of defeating enemy troops using a force that was extremely inferior in number.14 The rivalry parties in the battle were the powerful and formidable Cao Wei (with a million troops) against a comparably anaemic Sun Wu and Liu Shu alliance (with around a 100,000 troops). The lesson from the battle is about how a weak alliance beat the formidable troops due to the weakness of the ‘chained battleships’.

Before the battle, Cao Wei noticed that his soldiers, who had grown up in Northern China and had been trained to fight as land forces, couldn’t get used to war on a battleship and easily became nauseated and ill due to the motion of the waves and the unstable battleships fighting in the humid and hot southern area. Cao Wei decided to build colossal battleships, chained together, to accommodate all one million soldiers. The soldiers could run and even ride horses on the huge battleships like they did in the north prairie to overcome the motion of the waves.

The alliance took advantage of the chained and colossal battleships on the Yangtze River by launching a fire attack. A sweeping fire set by the military alliance from the downriver side was fanned by the strong southeast wind and devastated the million soldiers of Cao Wei on the upriver side of the Yangtze River. Although the probability of a southeast wind was low during the winter on the Yangtze River, geographically speaking,15 Cao Wei ignored this possibility in its ‘chained battleships’ plan, with devastating results. When the risk materialised, the fire on one ship and the spill over effect doomed all the ships that accommodated the one million soldiers, because the earlier affected ships could not be sunk as they were all chained together.

p.24

To some extent, the demise of the colossal ‘chained battleship’ can function as a model for the explanation of the TBTF bank structural problem. They are similar in four respects: huge in size; chained battleships are like interconnected banks; ignoring the rare southeast wind is like ignoring the low probability fat-tail risks;16 and a demise by fire and the banking crisis being caused by the spill over effect.17

To avoid the demise of the ‘chained battleships’, at least two approaches need to be considered. The first is the compartment design.18 An ideal mechanical approach to the colossal battleship scenario should be that, as a whole, it could exploit the force of scale while also being able to be disaggregat...