![]()

p.35

1 Transcendental empiricism

From Schelling to Benjamin and Bloch

(Spinoza, 1955: II, Prop. XVIII, Note II, p. 144)

(Scholem, 2007: diary entry dated 27 September 1917: 183)

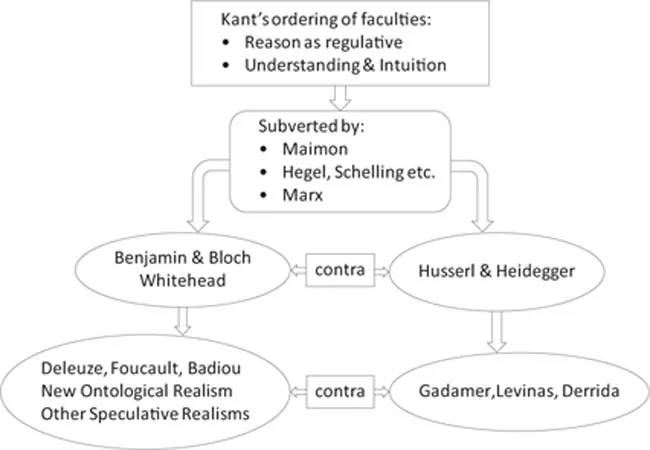

In this chapter I pursue a specific theoretical lineage, which begins with the active subversion of Kantian Transcendental philosophy both by certain contemporaries (such as Salomon Maimon) and by later contributors to the tradition of German Idealism (Hegel, Feuerbach and Marx), while choosing to focus, for reasons of brevity, on the overriding influence of F. W. Schelling on the German philosophers, Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin. Figure 1.1 maps out this trajectory, while seeking specifically to distinguish it from both the phenomenological and hermeneutic traditions of philosophy.

One of the objectives in tracing this lineage is to bring together two thinkers, Bloch and Benjamin, who have each contributed so much to our understanding of the role of art and creativity in an age of “mechanical reproduction”. I shall be returning to this theme again and again at certain points.1 To meet this objective, I have been obliged to spend less time than might otherwise be desirable in demonstrating the affinities, congruences, and isomorphisms that, in my view, clearly hold between the reasoning of Schelling and the that of my chosen pair of more contemporary philosophers.

Predecessors

The predecessors for Benjamin and Bloch’s revolutionary aesthetics are the German Idealists, especially Novalis and Schelling. Novalis precipitated a breaking away from efforts to ground knowledge in identical being, because he recognized that the very process of bringing consciousness into being veils consciousness from itself, thus imposing the necessity for self-critique. Moreover, the self’s familiarity with itself is something that is both indeterminate and non-discursive.2 For Novalis, then, finitude is subverted and exposed by the inescapable phenomenon of infinite regress, which the knowing subject is exposed to in virtue of the fact that higher forms of thinking are required to integrate both the thinking self and thought in itself. Much like modern theorists of computation, such as Peter Aczel, he argued that this infinite regression, must be actively embraced!

p.36

As Beiser (2002: 465) explains, it was Schelling “who fathered the basic principles and who forged the central themes of the absolute idealism that Hegel loyally defended and systematized from 1801 to 1804”. And even “if we admit that Hegel eventually saw farther than Schelling—a very generous concession—it is also necessary to add that he did so only because he stood on Schelling’s shoulders”.

Beiser (2002: 466) also articulates the reasons for the contemporary neglect of Schelling’s thought, saying that it “has much to do with the ill repute of metaphysics”, for “no one nowadays wants to be near metaphysics, the bogeyman of positivists, pragmatists, neo-Kantians, and postmodernists alike”. Beiser comments that Schelling’s notoriety for being a full-blown metaphysician “is somewhat ironic, given that, after 1809, Schelling himself turned against the metaphysical tradition, developing an interesting critique of conceptual thought in his later Positivephilosophie”. Nevertheless, Beiser (2002: 466) also explains the reasoning behind Schelling’s “ontological turn” away from the Kantian question of legitimate knowledge, for:

p.37

For the elder Schelling, the ontological question is captured by the existentialist conception that our existence necessarily precedes access to existence. In his terms, ‘unprethinkable’ being is both the presupposition of, and the beyond of thought. As I will demonstrate below, the distinction between logical being and historical being is exploited by Schelling in moving away from the flat ontology of logical space to the ordered ontology of historical time, with its movement from the logical past, to the present and future of being; especially, to the notion of personality as a “yet-to-be-completed” project. This ensures that human agency, itself, is exposed to the paradox that what comes later in logical time modifies what has come earlier, giving rise to an inexhaustible and indeterminable multiplication of the very means by which we refer to being and intervene in history: human freedom is vested in a profound contingency, in the historical possibility of things always being otherwise.

Gabriel makes this conception of Schelling’s the very core of his own transcendental ontology, insisting that his temporal ordering contrasts markedly with Hegel’s essentially timeless, circular logic. Nevertheless, he maintains that it should still not be conceived solely in subjective terms, because the self-relation of reality to itself is, in effect, achieved through our reference to it. He goes on to proclaim that both our thoughts about facts and the facts themselves are facts. Gabriel’s objective is to promote a New Ontological Realism (NOR) that can overthrow both the stodgy old version of metaphysical realism, which implies a “world without spectators”, and the contemporary version of Constructivism, which implies a “world with spectators”. To achieve success, his NOR must not only be able to explain the existence of spectators, but also the fact that spectators do not exist at all times and in all places. Furthermore, given that phenomena such as thoughts, institutions, and dreams are just as much a part of the object domain as objects such as projectiles, bacteria, or quarks that are more familiar to the natural sciences, advocates of NOR refuse to reduce all ontological questions to those posited by natural sciences.

Walter Benjamin, too, rejects the Kantian position that absolute reason is something entirely removed from the determinate features of intuition, choosing, instead, to embrace the notion of the absolute as embedded within a potentially infinite network of interconnected reflections, with both a structure and a genealogy conditioned by a dialectical interweaving of surfaces and their configurations. Moreover he also holds to the idea that the self-relation of reality to itself is achieved through our reference to it; a view most notably manifest in his onomatopoetic conception of non-sensuous sensuality and his genealogical analysis of the mimetic faculty as it passes, disruptively, from the unmediated cognition of natural marks to the mediated re-cognition of written inscriptions.

p.38

For his part, Ernst Bloch also argues for a dialectical conception of matter, which is grounded in a displacement of transcendental inquiry away from epistemological questions to those of ontology. For him, matter is the substrate of the objectively real possible, and transcendental inquiry interrogates the conditions required for something to be possible.

Transcendental ontology

As Gabriel (2011: ix) pronounces, “Transcendental ontology investigates the ontological conditions of our conditions of access to what there is”.3 The analysis of the concept of existence is therefore methodologically prior to the analysis of the subject’s access to existence. From the beginning, German Idealism was concerned with the question of the phenomenalization of being: What conditions have to be fulfilled by being (the world) in order for it to appear to finite thinkers who in turn change the structure of what there is by referring to it? However, the way that this question was approached from an Idealist perspective is cogently summarized by Slavoj Žižek (1996: 14):4

Gabriel explains that,

(Gabriel, 2011: x)

In accordance with Kant’s largely epistemological approach to the transcendental question, “there can be no absolute ontological gap between the order of things and the order of thought (of judging)”, because “the given must itself have a form that is at least minimally compatible with being grasped by thought”. As such, “the unifying activity that makes judgments about anything possible, yet which is not itself a judgment, had to be located within the subject” (Gabriel, 2011: xi)

For Kant, synthesis establishes relations within a given material, which is given through sensibility. In part, Hegel will attempt to replace the semantic atomism of this naïve “myth of the given” with a form of radical conceptual holism. For him, this very thought, that “what is given in sensory experience is conceptually structured”, transcends sensory experience by investigating “the relation holding between how something is given and the position to which it is given”, for the structure of experience “cannot itself be experienced among other objects”. Moreover, Hegel believes that Kant is “right in understanding subjectivity as constituting logical forms of reference (categories) outside of which nothing determinate can be apprehended”, however, he errs in not applying this thought to itself, for synthesis is a property of intentionality as such and, therefore, also applies to higher-order intentionality, that is, to theorizing about intentionality (Gabriel, 2011: xvi)!

p.39

In summary, for Gabriel (2011: xvii), “the Kantian metaphysics of intentionality is dialectically contradictory under self-application precisely because it does not reflect on its own position, on its own constitution”. In summary, “[a]ll of the so-called German idealists are looking for a transcendental method which is thoroughly dialectically stable under self-application. They all practice various forms of higher-order reflection thereby distinguishing between the levels of reflection”.

In Fichte, for example, Gabriel (2011: xviii) notes that “Being” is “the name for the facticity of absolute knowing, for the fact that we make the concept of knowledge explicit after having already claimed some knowledge or other about something or other”. Thus, Fichte’s related notion of “objectifying performance, which takes absolute knowing and thereby being as its object, is being’s self-reference”. Similarly, in The Grounding of Positive Philosophy, Schelling points out that, in his first Critique, Kant draws a twofold distinction between two forms of reason: (i) reason in its application to the sensible realm; and (ii) reason in its self-application. According to Schelling, however, “Kant mainly considers reason in this first sense, that is, in its capacity to structure sensible experience with the help of regulative ideas. In this way, Kant neglects ‘absolute reason’, that is, reason insofar as it explicates itself”. He also complains that for Kant, “Givenness is evidently not itself given, it is already a position within higher-order thought” (Gabriel, 2011: xix).

And Gabriel comments in approving terms, on Jacobi’s protest that Kant’s “transcendental idealism amounts to nihilism” for it “destroys the subject by reducing it to an empty logical form”, for “the only way to preserve the possibility of freedom” for Kant, was for the subject to dissolve “into its judgments” so that it could not possibly judge itself.

For Hegel, too, this Kantian autonomy of the subject “is defined with recourse to spontaneity, and spontaneity is only defined in opposition to receptivity. Hence, autonomy is contingent on heteronomy, the possibility of freedom presupposes the actuality of necessity, and so forth”. Nevertheless, Hegel also acknowledges that “the question to be answered remains Kantian: how is it possible to refer to anything that is not a judgment by a judgment?” (Gabriel, 2011: xii).

p.40

For Gabriel, himself, the thought that transcendental ontology adds to this Hegelian question is given by the maxim: “our thoughts about the way the world is are themselves a way the world is”. On the basis of this maxim It is therefore necessary to refer “to the ontological conditions of the conditions of possibility of truth-apt r...