![]()

1

Global phenomenon, local varieties

Lord Zhi of Yan paid his first court visit to Ancestral Zhou; the Zhou king bestowed upon Zhi twenty strings of cowry shells. Zhi cast this precious vessel for Si.

– Inscription on the Yan Hou Zhi Ding1

The only money they have here are these cowries or shells we carry them, being brought from the East Indies, and were charg’d to us at four pounds per cent, of which we gave 100 lb. for a salve.

– Thomas Phillips, Captain of the Hannibal, 16942

Across Afro-Eurasia

The longue durėe existence of cowrie money across the broad territories of the Afro-Eurasian continent and beyond requires a global explanation.

There are over 250 species of cowrie shells living across the world,3 but when cowrie money is mentioned, only two are the main forms: Cypraea moneta (Monetaria moneta) and Cypraea annulus (Monetaria annulus). The first one, native to the Maldives Islands, is the most important and is also called the money cowrie, as its scientific name indicates; the other is commonly known as the ring cowrie. Originating in the sea, especially in the waters surrounding the low-lying islands of the Maldives, Cypraea moneta (sometimes confused with Cypraea annulus) was transported to various parts of Afro-Eurasia in the prehistoric era, when it was often conferred a certain value, and where in many cases it was gradually transformed into a form of money in various societies for a long span of time.

As early as the turn of the last century, archaeologists and ethnographers found the wide use of cowrie shells in various societies, historically and contemporarily.4 Assuming diverse functions in politics, economy, culture and religion, cowrie shells were used in various rituals and daily decorations, and were widely believed to possess the powers of fertility, protection against evil or of warding off bad luck, but their most distinctive feature was their monetary role. Collected in the Maldives, cowrie shells were shipped to Bengal in exchange for rice, and it was in India that they gradually became money, probably as early as the fourth century. From India, cowries reached mainland Southeast Asia, where they functioned as money only in some places and societies. Cowrie shells were used as a medium of exchange in Assam, Arakan, Lower Burma, Siam, Laos and Yunnan. Cowries (both genuine cowries and their imitation forms made of jade, stone, bone, earthenware, gold, tin and bronze) have been found in archaeological sites throughout north China, and numerous bronze inscriptions record a popular cowrie-granting ritual during the Western Zhou period (1046 BCE–771 BCE), which has misled many scholars to assume that cowrie shells were first used as money in early China. They were not, but these shells played a dynamic part in shaping Chinese civilisation and culture.

Cowries also moved westwards to Africa. While evidence from the earlier period is vague, it is clear that by the fourteenth century, cowrie money had reached the upper and middle Niger River region, penetrating first the Mali Empire and then Songhay. From the sixteenth century onwards, Europeans brought cowries from the Indian Ocean to West Africa in such quantities that these shells eventually ruined the local money systems and economies, but greatly contributed to the prosperity of both the Atlantic slave and the palm oil trades, thus helping bring about the European domination of the world. From Africa, some cowrie shells were brought by European merchants to the New World for the fur trade or during the Middle Passage passing through North America and the Caribbean.

Therefore, there existed a cowrie money world which can be traced back to as early as the fourth century in India. It expanded to coastal areas in lower mainland Southeast Asia in the following centuries, and moved northwards to include present-day Yunnan in the ninth to tenth century transition; by the fourteenth century, the cowrie money world had already incorporated various societies in South Asia, Southeast Asia and West Africa; by the sixteenth century, with the arrival of the Europeans, the cowrie money world interacted and overlapped with part of the European world system into a global world in which cowrie money played a key role for the transatlantic slave trade and the European Industrial Revolution up until the nineteenth century.

In addition to this India-based cowrie money world, cowrie shells and other shells were also used as money in the Pacific Islands (particularly in New Guinea) and in native and colonial North American societies. These shells were crucial not only to local economies and their intra-trading with neighbouring groups or European traders, but also were significant for the maintenance and reproduction of these indigenous societies. Although not connected with the Indian cowrie monetary system, each mini cowrie monetary system within these societies had many parallels with the Afro-Eurasian one, especially in terms of its supply, inflation and demise, while each possessed its own local features and trajectory. Indeed, the pattern of European contact and collapse was shared with these cowrie monetary systems across the world.

Probably before being made into money, and certainly during and after being money, cowrie shells were used as ornaments, decorations, symbols of fertility and amulets for protection. Their aesthetic, political and religious functions assumedly predated their economic one, while the latter might have enhanced the former. Cowrie shells in gift granting and gift exchange in early China, for example, have indicated their multi-purposes conceptualised by Chinese elites in the early times.

This book provides a global examination of cowrie money within and beyond Afro-Eurasia from the archaeological period to the early twentieth century. The rise, evolution and fall of cowrie money from the fourth to the early twentieth century is a global phenomenon with local dynamics and varieties. By focusing on cowrie money in Indian, Chinese, Southeast Asian and West African societies and shell money in Pacific and North American societies, this book illustrates the economic and cultural connections, networks and interactions over a longue durée and in a cross-regional context, analysing locally varied experiences of cowrie money from a global perspective, arguing that cowrie money was the first global money that shaped Afro-Eurasian societies both individually and collectively, proposing a paradigm of the cowrie monetary world and thus engaging many local, regional, transregional and global themes.

The life of the cowrie mollusc

The term “cowrie” (“cowry” or “gowrie”) in Greek means “little pig,”5 and that is why early European texts referred these shells as pig shells. The very origin of the term can be traced to Sanskrit,6 as Paul Pelliot observed. But before going into the human view and uses of the cowrie, let us consider the biological story of this mollusc.

With a history of more than 100 million years, cowrie shells have been discovered in prehistoric archaeological sites in India, China, Southeast Asia, Europe, Africa and other parts of Afro-Eurasia. Today, they are widely found in most subtropical and tropical oceans between 30° N and 30° south of the equator.7 Most of them live in shallow waters no deeper than five metres, while a few occasionally live as deep as fifty metres or more. While algae seem to be their main source of food, most of them are carnivorous, some are omnivorous, and some mollusc-eating fish are their natural predators.8

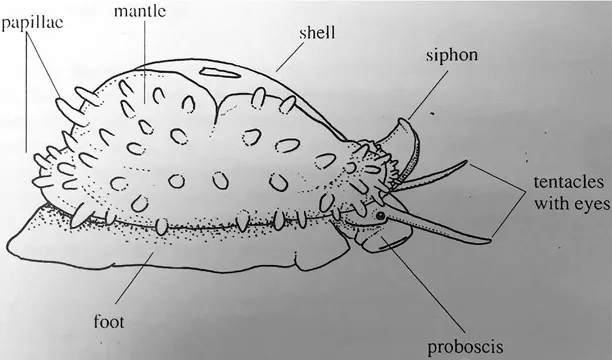

The body of the cowrie mollusc consists of its hard shell and the soft parts the shell encases, which include the mantle, foot and many external organs, such as syphons and tentacles (Figure 1.1). The mantle is the soft part that can envelop the shell completely, and it has many functions, such as secreting calcium and adding pigment to the shell, protecting and repairing cracks and holes, as well as being camouflage for the mollusc; the foot is used by many of the species to confuse predators such as reef fish; the syphon takes in water continuously and the tentacles gather information about the nearby surroundings; the radula, consisting of 50 or more rows of teeth, is the tool to grasp algae or cut pieces out of a sponge.9

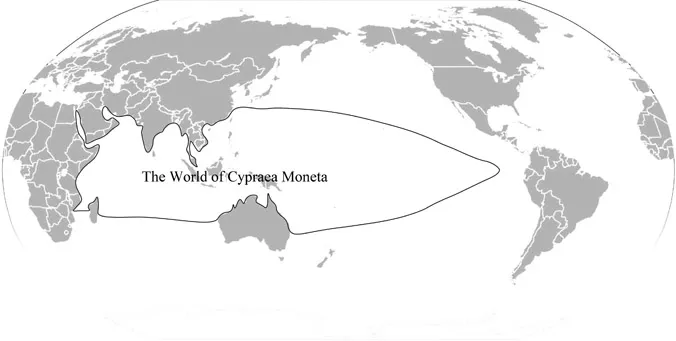

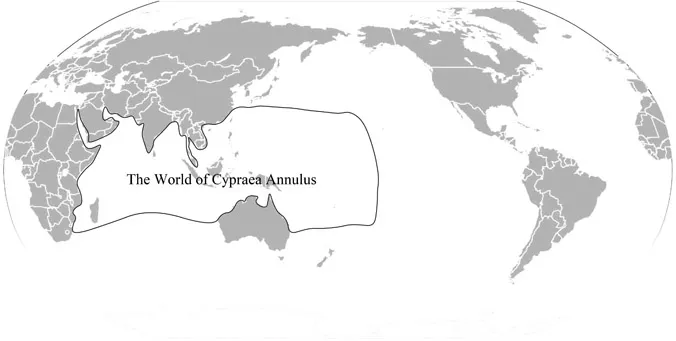

There are two different methods of cowrie reproduction: either predominantly by laying eggs or by direct reproduction.10 Cowries mature fairly quickly. Some take a year to reach adulthood while Cypraea moneta and Cypraea annulus take two or three years.11 Cypraea moneta and Cypraea annulus are abundant in the warm and shallow waters of the shores and lagoons of the Indian and Pacific oceans (Maps 1.1 and 1.2). Their habitats range from the Red Sea to Mozambique

Figure 1.1 External Anatomy of Cowrie12

Map 1.1 The World of Cypraea Moneta13

Map 1.2 The World of Cypraea Annulus14

in the west, to Japan, Hawaii, New Zealand and the Galapagos in the east.15 The Maldives was one of the main sources that places in Afro-Eurasia, such as Thailand, Burma (Arakan and Pegu) and Bengal looked to for acquiring cowrie shells (Cypraea moneta), being at that time the most important and oldest cowrie zone.16

Why Cypraea moneta? And why in the Maldives?

Why was it the species Cypraea moneta (and to some light extent Cypraea annulus) that was selected to be used as money in diverse societies?17 Principally, it was the cowrie shell’s particular physical features that made it an ideal form of money, especially for low-value transactions, at least in the beginning. First of all, cowries can be “accurately traded by weight, by volume or by counting.”18 They are light, on average slightly over one gram each and weighing about a pound for 400 pieces; they are solid, durable and difficult to break; they retain their shine and colour, unlike other species; and each and every one is of a similar size, with negligible differences.19 They are as durable, portable and firm, as is metal money, and their size and manufacture are even more convenient than metal coins, the latter requiring considerable labour and governmental effort to process (including mining and minting). These features made cowries incomparable with many other natural items used in the past as media of exchange.

Second, Cypraea moneta is special in that this species is naturally different from other cowries, in terms of size, colour or shape.20 Cypraea annulus was confused with Cypraea moneta in many archaeological excavations, as they look rather similar, but the former has a little yellow-orange circle on its crown, and so it can in fact be easily identified. Nature itself does not provide any possibility for counterfeit, nor human beings either.

Furthermore, Cypraea moneta were readily available and easily processed and shipped from the Maldives, which meant they were of very low value.21 This very attribute of low value created a double advantage. It made them more attractive than the costly manufacture of metal coins, and their low value and plentiful supply caused them to become popular as the preferred form of money for small daily transactions.

Finally, although cowrie shells fulfilled many cultural and religious functions, due to their low value and huge numbers, these non-monetary uses did not pose a challenge to their monetary role. In fact, it was the shortage of other forms of money such as gold, silver and copper that often threatened their supply as a medium of exchange.22 In sum, cowrie shells were long lasting, extremely durable, easy to handle, portable, hard to counterfeit and of the right unit value for market needs,23 which made them the first choice for a medium of exchange when they were first introduced in the early Bengali trading world. However, one may ask, since cowrie shells existed across the large global belt of warm seas, why were the Maldives the main supplier for Afro-Eurasia? This can be understood by appreciating the special features of these islands.

More than 130 of the over 200 described species of cowries are associated with coral reefs that provide the former an ideal environment.24 Coral reefs constitute a marine forest, hosting a greatly varied mixture of animals and plants, living and dead, including fish, sea cucumbers, molluscs, sponges, worms and so on. Cowries have evolved to live on coral reefs: their shell, colour and mantle are matched with the physical colours, shapes and shadows of the reef; their large feet help them move smoothly over the prickly surface ...