![]()

Chapter 1.

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) as a secondary source of metals

Global waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) generation was 41.8 million tons (Mt) in 2014, of which 9.5, 7.0 and 6.0 Mt belonged to EU-28, USA and China, respectively (StEP, 2015), and is likely to increase to 50 Mt in 2018 (Baldé et al., 2015). Low lifespan of electronic devices, perpetual innovation in electronics (Ongondo et al., 2015) and affordability of the devices (Wang et al., 2013) resulted in an unprecedented increase of WEEE. Despite the growing awareness and deterring legislation, most of the WEEE is disposed improperly, mostly landfilled (Cucchiella et al., 2015) or otherwise shipped overseas (Ladou and Lovegrove, 2008) to be treated in substandard conditions. Illegal shipping of such waste is a very important problem, currently dealt at an international level. When exported to the developing economies, the costs of WEEE treatment are externalized (Mccann and Wittmann, 2015).

Management of WEEE is of environmental and social concern with global implications due to its hazardous nature. The nature of the production, distribution and disposal of electronic devices include global chains (Breivik et al., 2014). The source of the global WEEE problem has its roots in lack of technologically mature solutions, poor enforcement and high costs of legal operations, and waste being a global commodity in contrast with the regulations (Baird et al., 2014). It is simply cheaper for the end users to ship the waste material overseas. Lack of an effective technical solution, so as to efficiently and selectively recovery metals plays a major role (Lundgren, 2012). In addition to all the hazards originating from WEEE, manufacturing electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) consumes considerable amounts of minerals, particularly metals. Electronics industry is the third largest consumer of gold (Au), responsible of 12% of the global demand, along with 30% for copper (Cu), silver (Ag) and tin (Sn) (Mccann and Wittmann, 2015). More than one million people in 26 countries across Africa, Asia and South America work in gold mining, mostly in unregistered substandard conditions (Schipper et al., 2015).

The rapid increase of EEE production and consequent WEEE generation are reliant on access to a number of raw materials. Many of them are critical due to their limited supply, potential usage in other applications and economic importance (Bakas et al., 2014). The number of materials used in hi-tech products tremendously increased. WEEE is a complex mixture of different materials in various concentrations. Modern devices encompass up to 60 elements, with an increase of complexity with various mixtures of compounds (Bloodworth, 2014). These elements go into the manufacture of microprocessors, circuit boards, displays, and permanent magnets usually in tiny quantities and often in complex alloys (Reck and Graedel, 2012). Discarded printed circuit boards (PCB) are an important secondary source of valuable metals. All EEE contains PCB (Marques, 2013) of various size, type and composition (Duan et al., 2011). These materials are a complex mixture of metals, polymers and ceramics (Yamane et al., 2011).

WEEE contains considerable quantities of valuable metals such as base metals, precious metals and rare earth elements (REE). These ‘specialty’ metals are used to enable enhanced performance in modern high-tech applications and are collectively termed technology metals (Reck and Graedel, 2012). Typically, a PCB includes very high concentrations of metals such as copper (Cu), iron (Fe), aluminum (Al), and nickel (Ni) along with precious metals such as gold (Au), silver (Ag), platinum (Pt), and palladium (Pd). Metal concentrations of discarded PCB are much higher than those of the natural ores. Metal recovery from discarded WEEE is conventionally carried out by pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical methods, which have their own drawbacks and limitations (Cui and Zhang, 2008). The composition of PCB after processing from a WEEE treatment plant is 38.1% ferrous metals, 16.5% non-ferrous metals, and 26.5% plastic, and 18.9% others (Bigum et al., 2012). Precious metals are the main driver of recycling (Hagelüken, 2006), viz. Au has the highest recovery priority; followed by copper (Cu), palladium (Pd), aluminium (Al), tin (Sn), lead (Pb), platinum (Pt), nickel (Ni), zinc (Zn) and silver (Ag) (Wang and Gaustad, 2012). On the other hand, the intrinsic value of non-precious technology (speciality) metals is increasing (Tanskanen, 2013) owing to decreasing concentration of precious metals in PCB (Luda, 2011; Yang et al., 2011).

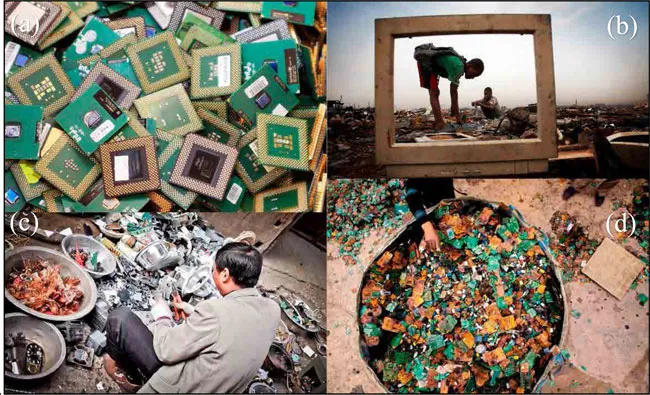

Informal recycling of WEEE has catastrophic effects on the people and the environment. In Europe, where there is a tradition of preventative legislation and robust policy measures, only 35% (3.3 Mt) of WEEE is reported to be officially collected (Huisman et al., 2015), and the rest is speculated to be exported, treated under substandard conditions, or simply thrown in waste bins (Figure 1-1). The hazards associated with improper WEEE management come twofold: degradation of the environment (Song and Li, 2014) and loss of valuable resources (Oguchi et al., 2013). Despite its toxicity, PCB contains valuable materials that could be recovered to yield both environmental and economic benefits (Kumari et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2010).

Figure 1-1: Informal processing of electronic waste; discarded central processing units (CPU) for recycling (a), electronic waste dumb in Ghana (b), substandard processing in Shanghai, China (c) worker in Guiyu, China (d).

Urban areas are densely populated by obsolete end-of-life (EoL) electronic devices. These waste materials are an important secondary source of technology metals (Ongondo et al., 2015). However, their inclusion back in the economy has several bottlenecks, including technological limitations, and low collection rates of the devices and poor enforcement of the law concerning their management. These obstacles are interconnected, and amendment of one positively affects the other. In a circular economy, material loops are closed by recycling of discarded products, urban mining of EoL products and mining of current and future urban waste streams (Jones et al., 2013).

In this PhD research, novel metal recovery technologies from WEEE were investigated. An emphasis was given to biological methods. Biohydrometallurgy or urban biomining, using microbes for processing metals, enables environmentally sound and cost-effective processes to recover metals from waste materials (Ilyas and Lee, 2014a). In this context, microbial leaching (bioleaching) of metals from waste materials is an attractive field of research with vast potential. Moreover, conventional chemical technologies, despite their several bottlenecks and disadvantages, are effective in the leaching of metals from primary ores. However, their effectiveness in polymetallic, anthropogenic WEEE is largely unexplored. This research addresses the knowledge gap on two metal extraction approaches, namely chemical and biological, from a recent secondary source of metals, the essential parameters of these metal recovery processes, subsequent selective recovery techniques, techno-economic and sustainability assessment, and scale up potential of the technology.

1.2 Research goals and questions

The main objective of this work is to develop a sustainable method to recover metals from electronic waste. Moreover, the optimum process parameters are studied, different routes, e.g. biological and chemical, are explored and compared, as well an overall techno-economic and sustainability assessment of the newly developed technology were given. Application of biological methods in production of metals from primary sources is an established technology: more than 15% of Cu production is carried out by bacteria (Schlesinger et al., 2011). These biological processes are typically environmentally friendly, and cost effective processes, where the pollutant production is minimal and process input are simply the nutrient requirements.

The following hypotheses are formulated and tested:

1. What is the best effective method to recover metals selectively?

Recovery of metals from WEE is a necessity, in order to meet the demand for raw materials (Gu et al., 2016). Currently, there are several alternatives, such as pyrometallurgical, hydrometallurgical routes and recently emerging bio-based route, a technique that employs microbial cells to extract and recover metals from waste. Pyrometallurgy is an advanced refining technology, currently employed at full scale in commercial plants (Akcil et al., 2015). In this research, the most effective method is investigated and benchmarked to best available technologies (BAT).

2. Which metals should be given priority to be recovered?

Metals in WEEE are of variable abundance, chemical composition and form. They include base metals, precious metals and specialty metals (Reck and Graedel, 2012). The concentration and occurrence of individual metals depend on the type of waste, manufacture years and the source (Marques, 2013). There is no one-sizes-fits-all strategy to recover metals from electronic waste. Thus, it is essential to develop a waste- and metal-specific technology to recover metals from electronic waste. A number of relevant selection criteria include economic value of the metals, the criticality and technological barriers. This research question addresses the prioritizing of metal recovery from WEEE.

3. How effective are biological and chemical approaches?

Biological methods, leaching of metals mediated by microbial cells (bioleaching), are proven feasible for primary ores. Over 20% of Cu is produced by bacteria (Schlesinger et al., 2011). However, its application to secondary ores is largely unknown. Chemical processing, on the other hand, is an established technology for the primary ores and a number of approaches have been taken to suggested them from secondary ores, including WEEE (Cui and Zhang, 2008). However, due to dissimilar chemical composition of the materials to natural ores and large variety of metals, the recovery processes are fundamentally different. This research question investigates the effectiveness of two approaches, namely chemical and biological routes, in terms of selectivity, efficiency and scale-up potential.

4. How sustainable and feasible are the selected methods to recover metals from electronic waste?

Emerging bio-based technologies are regarded as environmentally friendly, as they do not emit hazardous gases or exploit corrosive reagents, and often autonomously remediate their potential hazards (Watling, 2015). Moreover, their energy requirement is minimal, as microbial cells require low energy to maintain their metabolism. This gives the biological route an advantage over conventional technologies. In this research, the sustainability assessment and techno-economic assessment of the newly developed technology are investigated.

1.3 Research approach and methodology

Complexity of the waste material requires innovative approaches in order to sustainably and selectively recover metals from WEEE. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach is aimed, entrenching fields of environmental engineering, metallurgical engineering, environmental biotechnology, process development and sindustrial ecology. In this dissertation, the main dimensions were included for research goal achievement, namely, technology, sustainability, and the environment. For instance, components of leaching of metals from WEEE and its subsequent recovery are fundamentally different. Similarly, methods to develop a process, carry out cost analysis, and evaluate the environmental profile of a future technology are dissimilar. Nonetheless, it is required that those interrelated elements are analyzed altogether. Thus, a multidisciplinary approach was taken due to the complexity of the material, and this allowed to come out with a holistic overview of the collective outcome of all dimensions of sustainability.

1.4 Structure of this dissertation

The structure of this dissertation closely follows the research approach as given above in 1.3. Figure 1-2 illustrates the interaction of the chapters. The contents of the individual chapters are as follows:

Chapter 1: Introduction presents an overarching view of the entire dissertation, including a brief background of WEEE as a secondary source of metals and research methodology. The research goals and questions, the research approach and methodology, the scope and boundaries, the targeted audience are also given in this introductory chapter.

Chapter 2: Literature review gives a comprehensive literature analysis of the current status of WEEE and state of research on metal recovery. A holistic approach is taken and all elements of WEEE management are investigated. In this chapter, research gaps are identified after a critical analysis of the published literature.

Chapter 3: Literature review investigates the state-of-the-art on emerging biorecovery methods of metals from WEEE including novel bioleaching, bioprecipitation and biosorption technologies. In this chapter, perspectives on the knowledge gap on bioprocessing of a valuable secondary source is identified in the light of the recent developments in this...