![]()

PART 1

LEARNING THEORY

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A COMPREHENSIVE UNDERSTANDING OF HUMAN LEARNING

Already in the 1970s Knud Illeris was well known in Scandinavia for his developing work on project studies in theory and practice. In this work, learning theory was applied, mainly by a combination of Jean Piaget’s approach to learning and the so-called ‘critical theory’ of the German–American Frankfurt School that basically connected Freudian psychology with Marxist sociology. In the 1990s, Illeris returned to his learning theoretical roots, now involving many other theoretical approaches in the general understanding of learning, which was first presented in The Three Dimensions of Learning and later fully worked out in How We Learn: Learning and Non-learning in School and Beyond. The following chapter presents the main ideas of this understanding and is an elaborated version of the presentation Illeris made at a conference in Copenhagen in 2006 when the Danish version of How We Learn was launched. The article was published as the opening chapter in Contemporary Theories of Learning, Knud Illeris (ed.) 2009.

Background and basic assumptions

Since the last decades of the nineteenth century, many theories and understandings of learning have been launched. They have had different angles, different epistemological platforms and a very different content. Some of them have been overtaken by new knowledge and new standards, but in general we have today a picture of a great variety of learning theoretical approaches and constructions, which are more-or-less compatible and more-or-less competitive on the global academic market. The basic idea of the approach to learning presented in this chapter is to build on a wide selection of the best of these constructions, add new insights and perspectives and in this way develop an overall understanding or framework, which can offer a general and up-to-date overview of the field.

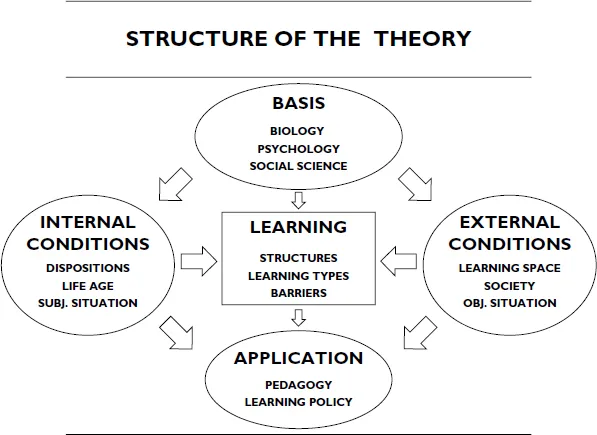

Learning can broadly be defined as any process that in living organisms leads to permanent capacity change and which is not solely due to biological maturation or ageing (Illeris 2007, p. 3). I have deliberately chosen this very open formulation because the concept of learning includes a very extensive and complicated set of processes, and a comprehensive understanding is not only a matter of the nature of the learning process itself. It must also include all the conditions that influence and are influenced by this process. Figure 1.1 shows the main areas which are involved and the structure of their mutual connections.

Figure 1.1 The main areas of the understanding of learning.

On the top I have placed the basis of the learning theory, i.e. the areas of knowledge and understanding which, in my opinion, must underlie the development of a comprehensive and coherent theory construction. These include all the psychological, biological and social conditions which are involved in any learning. Under this is the central box depicting learning itself, including its processes and dimensions, different learning types and learning barriers, which to me are the central elements of the understanding of learning. Further there are the specific internal and external conditions which are not only influencing but also directly involved in learning. And finally, the possible applications of learning are also involved. I shall now go through these five areas and emphasise some of the most important features of each of them.

The two basic processes and the three dimensions of learning

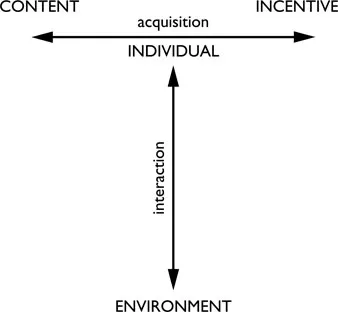

The first important condition to realise is that all learning implies the integration of two very different processes, namely an external interaction process between the learner and his or her social, cultural or material environment, and an internal psychological process of elaboration and acquisition.

Many learning theories deal only with one of these processes, which of course does not mean that they are wrong or worthless, as both processes can be studied separately. However, it does mean that they do not cover the whole field of learning. This may, for instance, be said of traditional behaviourist and cognitive learning theories focusing only on the internal psychological process. It can equally be said of certain modern social learning theories which – sometimes in explicit opposition to this – draw attention to the external interaction process alone. However, it seems evident that both processes must be actively involved if any learning is to take place.

When constructing my model of the field of learning (Figure 1.2), I started by depicting the external interaction process as a vertical double arrow between the environment, which is the general basis and therefore placed at the bottom, and the individual, who is the specific learner and therefore placed at the top.

Figure 1.2 The fundamental processes of learning.

Next I added the psychological acquisition process as another double arrow. It is an internal process of the learner and must therefore be placed at the top pole of the interaction process. Further, it is a process of integrated interplay between two equal psychological functions involved in any learning, namely the function of managing the learning content and the incentive function of providing and directing the necessary mental energy that runs the process. Thus the double arrow of the acquisition process is placed horizontally at the top of the interaction process and between the poles of content and incentive – and it should be emphasised that the double arrow means that these two functions are always involved and usually in an integrated way.

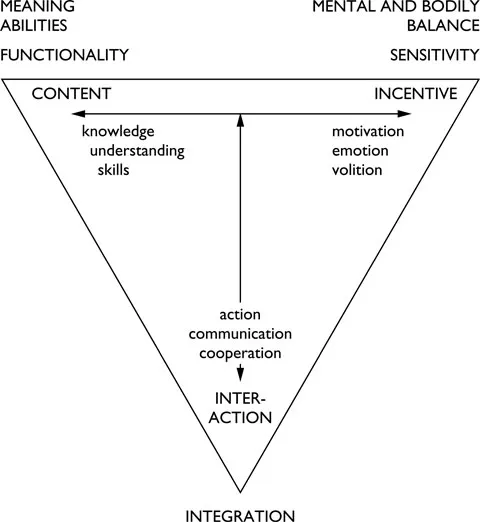

As can be seen, the two double arrows can now span out a triangular field between three angles. These three angles depict three spheres or dimensions of learning, and it is the core claim of the understanding that all learning will always involve these three dimensions.

The content dimension concerns what is learned. This is usually described as knowledge and skills, but also many other things such as opinions, insight, meaning, attitudes, values, ways of behaviour, methods, strategies, etc. may be involved as learning content and contribute to building up the understanding and the capacity of the learner. The endeavour of the learner is to construct meaning and ability to deal with the challenges of practical life and thereby an overall personal functionality is developed.

The incentive dimension provides and directs the mental energy that is necessary for the learning process to take place. It comprises such elements as feelings, emotions, motivation and volition. Its ultimate function is to secure the continuous mental balance of the learner and thereby it simultaneously develops a personal sensitivity.

These two dimensions are always initiated by impulses from the interaction processes and integrated in the internal process of elaboration and acquisition. Therefore, the learning content is, so to speak, always ‘obsessed’ with the incentives at stake – e.g. whether the learning is driven by desire, interest, necessity or compulsion. Correspondingly, the incentives are always influenced by the content, e.g. new information can change the incentive condition. Many psychologists have been aware of this close connection between what has usually been termed the cognitive and the emotional (e.g. Vygotsky 1978; Furth 1987), and recently advanced neurology has proven that both areas are always involved in the learning process, unless in cases of very severe brain damage (Damasio 1994).

Figure 1.3 The three dimensions of learning and competence development.

The interaction dimension provides the impulses that initiate the learning process. This may take place as perception, transmission, experience, imitation, activity, participation, etc. (Illeris 2007, pp. 100ff.). It serves the personal integration in communities and society and thereby also builds up the sociality of the learner. However, this building up necessarily takes place through the two other dimensions.

Thus the triangle depicts what may be described as the tension field of learning in general and of any specific learning event or learning process as stretched out between the development of functionality, sensibility and sociality – which are also the general components of what we term competencies.

It is also important to mention that each dimension includes a mental as well as a bodily side. Actually, learning begins with the body and takes place through the brain, which is also part of the body, and only gradually is the mental side separated out as a specific but never independent area or function (Piaget 1952).

An example from everyday school life

In order to illustrate how the model may be understood and used, I shall take an everyday example from ordinary school life (which does not mean that the model only deals with school learning).

During a chemistry lesson in the classroom, a teacher is explaining a chemical process. The students are supposed to be listening and perhaps asking questions to be sure that they have understood the explanation correctly. The students are thus involved in an interaction process. But at the same time, they are supposed to take in or to learn what the teacher is teaching, i.e. psychologically to relate what is taught to what they should already have learned. The result should be that they are able to remember what they have been taught and, under certain conditions, to reproduce it, apply it and involve it in further learning.

But sometimes, or for some students, the learning process does not take place as intended, and mistakes or derailing may occur in many different ways. Perhaps the interaction does not function because the teacher’s explanation is not good enough or is even incoherent, or there may be disturbances in the situation. If so, the explanation will only be picked up partially or incorrectly, and the learning result will be insufficient. But the students’ acquisition process may also be inadequate, for instance because of a lack of concentration, and this will also lead to deterioration in the learning result. Or there may be errors or insufficiencies in the prior learning of some students, making them unable to understand the teacher’s explanation and thereby also to learn what is being taught. Much of this indicates that acquisition is not only a cognitive matter. There is also another area or function involved concerning the students’ attitudes to the intended learning: their interests and mobilisation of mental energy, i.e. the incentive dimension.

In a school situation, focus is usually on the learning content; in the case described it is on the students’ understanding of the nature of the chemical process concerned. However, the incentive function is also still crucial, i.e. how the situation is experienced, what sort of feelings and motivations are involved, and thus the nature and the strength of the mental energy that is mobilised. The value and durability of the learning result is closely related to the incentive dimension of the learning process.

Further, both the content and the incentive are crucially dependent on the interaction process between the learner and the social, societal, cultural and material environment. If the interaction in the chemistry lesson is not adequate and acceptable to the students, the learning will suffer, or something quite different may be learned, for instance a negative impression of the teacher, of some other students, of the subject or of the school situation in general.

The four types of learning

What has been outlined in the triangle model and the example above is a concept of learning which is basically constructivist in nature, i.e. it is assumed that the learner him-or herself actively builds up or construes his/her learning as mental structures. These structures exist in the brain as dispositions that are usually described by a psychological metaphor as mental schemes. This means that there must in the brain be some organisation of the learning outcomes since we, when becoming aware of something – a person, a problem, a topic, etc. – in fractions of a second are able to recall what we subjectively and usually unconsciously define as relevant knowledge, understanding, attitudes, reactions and the like. But this organisation is in no way a kind of archive, and it is not possible to find the different elements at specific positions in the brain. It has the nature of what brain researchers call ‘engrams’, which are traces of circuits between some of the billions of neurons that have been active at earlier occasions and therefore are likely to be revived, perhaps with slightly different courses because of the impact of new experiences or understandings.

However, in order to deal systematically with this, the concept of schemes is used for what we subjectively tend to classify as belonging to a specific topic or theme and therefore mentally connect and are inclined to recall in relation to situations that we relate to that topic or theme. This especially applies to the content dimension, whereas in the incentive and interaction dimensions we would rather speak of mental patterns. But the background is similar in that motivations, emotions or ways of communication tend to be organised so that they can be revived when we are oriented towards situations that ‘remind’ us of earlier situations when they have been active.

In relation to learning, the crucial thing is that new impulses can be included in the mental organisation in various ways, and on this basis it is possible to distinguish between four different types of learning which are activated in different contexts, imply different kinds of learning results and require more or less energy. (This is an elaboration of the concept of learning originally developed by Jean Piaget, e.g. Piaget 1952; Flavell 1963.)

When a scheme or pattern is established, it is a case of cumulative or mechanical learning. This type of learning is characterised by being an isolated formation, something new that is not a part of anything else. Therefore, cumulative learning is most frequent during the first years of life, but later occurs only in special situations where one must learn something with no context of meaning or personal significance, for example a PIN code. The learning result is characterised by a type of automation that means that it can only be recalled and applied in situations mentally similar to the learning context. It is mainly this type of learning which is involved in the training of animals and which is therefore also referred to as conditioning in behaviourist psychology.

By far the most common type of learning is termed assimilative or learning by addition, meaning that the new element is linked as an addition to a scheme or pattern that is already established. One typical example could be learning in school subjects that are usually built up by means of constant additions to what has already been learned, but assimilative learning also takes place in all contexts where one gradually develops one’s capacities. The results of learning are characterised by being linked to the scheme or pattern in question in such a manner that it is relatively easy to recall and apply them when one is mentally oriented towards the field in question, for example a school subject, while they may be hard to access in other contexts. This is why problems are frequently experienced in applying knowledge from a school subject to other subjects or in contexts outside of school (Illeris 2009).

However, in some cases, situations occur where something takes place that is difficult to immediately relate to any existing scheme or pattern. This is experienced as something one cannot really understand or relate to. But if it seems important or interesting, if it is something one is determined to acquire, this can take place by means of accommodative or transcendent learning. This type of learning implies that one breaks down (parts of) an existing scheme and transforms it so that the new situation can be linked in. Thus one both relinquishes and reconstructs something, and this can be experienced as demanding or even painful, because it is something that requires a strong supply of mental energy. One must cross existing limitations and understand or accept something that is significantly new or different, and this is much more demanding than just adding a new element to an already existing scheme or pattern. In return, the results of such learning are characterised by the fact that they can be recalled and applied in many different, relevant contexts. It is typically experienced as having understood or got hold of something which one really has internalised.

Finally, over the last few decades it has been pointed out that in special situations there is also a far-reaching type of learning that has been variously described as significant (Rogers 1951, 1969), expansive (En...