The looming presence of the Pompeian defenses has shaped the understanding of the genesis of Pompeii in a manner that no other single monument has been able to do. Most modern hypotheses concerning the formation of the city have rested on their sequencing and dating. Gates such as the Porta Ercolano have remained exposed ever since their first discovery in the late 1700s, thereby influencing the views of countless visitors and scholars. Although the excavations of Pompeii have focused on recovering the city as it froze in 79 CE, the city walls were one of the few monuments where investigations could continue to shed light on the genesis of the city. The reasons for this approach were multiple. The fortifications of Pompeii represent the first tangible signs of an organized community preoccupied with defense. Understanding the line of the defenses meant that authorities could map the limits of the city – or so they thought at the time – and detail the succession of construction techniques used in fortifications and by extension the city. Given their location on the fringe of Pompeii, excavators could reach lower strata to date the site without destroying ancient floors or streets. Due to their size, large parts of the defenses would remain intact despite extensive investigations. Because the city gates anchored the urban grid, logic dictated that the walls were the oldest structure in Pompeii. These combined factors mean that scholars have long contemplated the fortifications, in the process producing many divergent theories concerning the development of Pompeii. Although a broad common consensus now exists for their construction sequence, many of the debates are still open to question.

Despite the importance of Pompeii’s fortifications, no summary of their recovery exists. We know little about their state of preservation at the time of excavation and subsequent conservation. The sheer scale and the eclectic nature of the construction techniques present in the remains mean that the monument has resisted systematic evaluations. The Porta Stabia, one of the earliest gates, is encased in much later Roman concrete. Farther east, the circuit emerges near the Porta Nocera to display travertine masonry up to the amphitheater, where it turns into concrete again. After the amphitheater, the stretch of wall up to the Porta Ercolano displays a socle of travertine with surmounting courses of tuff masonry of varying height. Rough sections of later Roman concrete often interrupt the curtain. A tract remains buried at the height of Tower IX, whereas the walls emerge sporadically from beneath later housing built on the western side and from structures between the Temple of Venus and the Doric Temple. The remains of eleven towers built at the turn of the first century BCE are unevenly spaced throughout the circuit, with concentrations on the northern and southern sides. The location of a twelfth remains contested. The piecemeal excavations, the divergent recording standards of past investigations, and the patchwork of masonry complicate the debate concerning the development of the walls. The fundamental lack of knowledge for the early city adds to the problem.

The city walls and the theories on the urbanization of Pompeii

With only 2 percent of Pompeii excavated below the level of 79 CE, the various theories associating the development of the city with the fortifications are approximations.1 The debate divides into two main camps: those favoring a grand central design of the city and those who see it growing from an old core, also known as the Altstadt – or old city. On occasion, these two camps have combined into a third where the grand design and the old core represent different periods of development, each following independent stages of design. The original nineteenth-century hypothesis, known as the grand Pompeii theory, envisioned the city as founded in a single coherent urban design in the sixth century BCE. Its defenses consisted of a travertine-faced agger-type fortification – the equivalent of the first Samnite enceinte built in the late fourth century BCE that visitors see today.2 Understanding the dynamics and reasons for such a massive beginning to Pompeii were daunting, leading to some more nuanced approaches to the single foundation theory. Giuseppe Fiorelli and Antonio Sogliano hypothesized the presence of earlier defenses where a fossa-agger system, composed of an earthen embankment and reinforced with a surmounting palisade and an exterior ditch, first enclosed the city. Although not in the form or date they had envisioned, the eventual discovery of the Pappamonte and the Orthostat enceintes partially validated Fiorelli and Sogliano’s hypothesis. Based on the orthogonal plan of the city, Sogliano also suggested the presence of an early gate on the western end of the via di Nola as a logical counterpart of the Porta Nola.3 Although Maiuri later discredited this idea, the recent identification of a postern beneath the House of Fabius Rufus (VII.16.22) confirmed Sogliano’s hypothesis almost a century after his first assumptions.4 Such long-term debates are typical of Pompeian studies.

In 1913, Francis Haverfield proposed a new model where Pompeii first developed around a smaller core centered on the Forum that was preserved in the irregular layout of the streets in this corner of the city.5 A few decades later, Armin Von Gerkan elaborated the theory, identifying the vicolo dei Soprastanti, the via degli Augustali, the vicolo del Lupanare, and the via dei Teatri as the limits of an old core that he called the Altstadt (see plate 2).6 This perimeter of streets was a relic of a path that followed a vanished fortified agger. Gates opening onto regional roads would become the major arteries of the later city. After the construction of the outer fortification in the late sixth century BCE, the new city, or Neustadt, would expand into its current layout. Hans Eschebach refined this model by identifying two phases of development for the Altstadt. The first settlement developed as an urbs quadrata, or squared city, with four neighborhoods on each side of the central Forum. This core gradually expanded in a second phase into the limits of the Altstadt. Eschebach also projected an earlier fortification defending the urbs quadrata after excavations identified the remains of a robbed out wall in the vicolo del Lupanare.7 Much of this theory relied on Amedeo Maiuri’s discovery of a hypogeum beneath the Terme Stabiane, which he believed was an Etruscan tomb. Ancient custom strictly dictated that funerary structures must be located outside the city walls. John Ward-Perkins was a vocal critic of the notion of the urbs quadrata; it has since been dismissed because Maiuri’s hypogeum is likely not a tomb.8

The Altstadt theory, in its various nuances, dominated the hypotheses concerning the development of early Pompeii until Stefano De Caro excavated and dated the Pappamonte fortification to the sixth century BCE. This discovery essentially reversed the trend and returned to the idea of a grand foundation.9 However, De Caro did not dispense with the Altstadt altogether, envisioning it instead as a main habitation core with a surrounding swath of open terrain protected by the Pappamonte circuit. Rather than an elaborate stone fortification, a simple palisade, road, or drainage ditch would explain Von Gerkan’s Altstadt perimeter being preserved in the later streets.10 Since then, archaeological excavations in Regio VI have further refined the Altstadt theory, indicating that it actually represents a retreat of the urban expanse into smaller, more defensible, confines in the fifth century BCE.11 After the construction of the first Samnite enceinte in the late fourth/early third century BCE, Pompeii gradually expanded back out into the Neustadt after Campania entered the Roman sphere of influence.

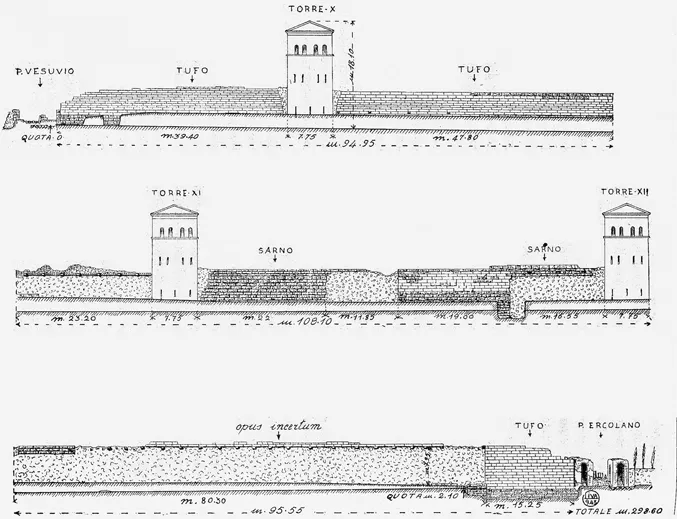

The construction materials used in the circuits have played a critical part in ideas concerning the development of Pompeii. Giuseppe Fiorelli first defined the architectural history of Pompeii associating it broadly with the main historical developments occurring on the Italian peninsula. He described three distinct periods connected to the use of construction materials: limestone (travertine) as the oldest, tuff associated with the Samnite city, and concrete and brick dating to the Roman period. August Mau later refined these periods to five by dividing the Roman period into the early colony, the early empire, and finally the post–62 CE earthquake reconstructions.12 The framework still forms the basic premise for the architectural history of Pompeii, although recent approaches rightly blur the rigid periodization because materials and techniques, once invented, can cross over into later periods. The identification of a separate limestone phase is particularly debatable due to the paucity of remains.13 Nevertheless, Fiorelli’s strict periodization almost certainly swayed Overbeck and Mau when they first formulated the construction sequence of the fortifications in 1875 and later influenced Maiuri when he reframed their development in the late 1920s (see Figure 1.1).

The use of opus incertum in the towers, the gate vaults, and the curtain wall in the late second century BCE is similarly part of a debate concerning the development of Pompeii and a broader discussion on the genesis of concrete in Roman architecture. A principle problem with these hypotheses is that the practice of dating masonry is a notoriously imprecise endeavor.14 The earliest Pompeianists,

Figure 1.1 Maiuri’s drawing of the north side of the fortifications between the Vesuvio and Ercolano gates detailing the various types of masonry. (After Maiuri 1943, fig. 1)

such as Romanelli, Mazois, and more recently Richardson, viewed the application of opus incertum in the towers and the curtain wall as repairs needed after the Sullan siege as a response to the unrest caused by Caesar’s assassination.15 Niccolini and Overbeck-Mau dismissed this notion, believing that the long tracts of concrete are too extensive to represent the damage of a single siege.16 Soon afterward, Sogliano discovered a graffito...