![]()

1

Introduction

The Internet of People, Things and Services (IoPTS): Workplace Transformations

Claire A. Simmers and Murugan Anandarajan

Introduction

In 2006, we published a volume on the Internet and workplace transformations (Anandarajan, Teo, & Simmers, 2006). At that time, unknown to us, that volume was the midpoint of our journey in examining the interrelationships between user behavior and information and communication technologies (ICT) in the workplace. Our work began as the Internet was becoming more widely used in the business setting, and we investigated factors that influenced end-user adoption of the Internet in the workplace (Anandarajan, Simmers, & Igbaria, 2000). We extended our research by examining the multidimensionality of positive and negative personal Internet usage in the workplace, and we saw the personal and the work increasingly overlapping, enabling unprecedented accessibility to unlimited information on a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week basis. We were no longer bound to our physical location; through the Internet, we could be anywhere in the world. The troubling and promising ways the Internet transformed our workplaces were due to the vastness of information, the disaggregation of work and location, and the rapid worldwide adoption.

Our attention again shifted in sync with ICT advancements, with the increasing portability of devices. We were no longer tethered to desktop devices, but had laptops, tablets, and smart phones owned by the organization, or just as likely owned by the individual. This convergence and overlapping of devices and ownerships allowed for further extension of the 24/7 workplace, as work could be accessed on any device at any time and any place. The information world was in our pockets.

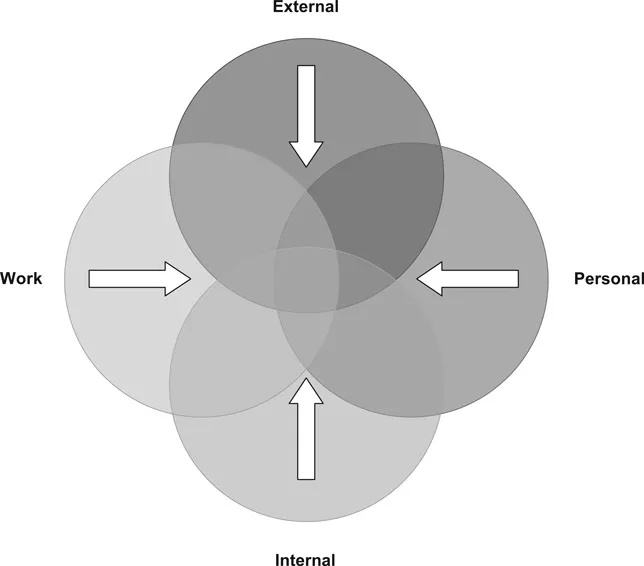

Layered onto hardware portability are advancements in the interconnectivity of the workplace. We are now able, primarily through the “cloud”, to link our portable devices to anyone and anything in a spider web of connectivity increasingly known as the Internet of People, Things and Services (Eloff, Eloff, Dlamini, & Zielinski, 2009). IoPTS is about linking the physical world and the digital world through sharing common protocols facilitating interoperationality. This is a world of autonomous communication between intelligent devices that are sensitive to a person’s presence and respond by performing specific services that enhance a person’s lifestyle (Piccialli & Chianese, 2017). There are countless applications; more are introduced daily, and even more are planned for the future. Energy efficiency, health-care, transportation coordination, household appliances, wearables, and self-driving cars are just a few examples (Gershenfeld & Vasseur, 2014). This level of interconnectivity smashes the already blurred boundaries between work and personal lives that we explored in the 2006 volume (Anandarajan, et al., 2006)). Additionally, the porousness of an organization’s internal and external boundaries increases; the impacts of the increasing convergence between these four forces are what we explore in this volume. This dynamism is illustrated in Figure 1.1, which shows the increasing convergence (represented by the four arrows) of the spheres of work and personal with the internal and external boundaries of the organization.

Figure 1.1 IoPTS Producing Increasing Convergence in the Workplace

Background

Since our 2006 volume, worldwide Internet usage continued to grow. Penetration (defined as the number of users divided by the total population) rose from 1.5% in Africa in 2005 to 31.2% in 2017 and from 67.4% in North America in 2005 to 88.1% in 2017. There are now 3.9 billon Internet users worldwide, which represents over half the world’s population (51.7%) (World Internet Users Statistics, 2017). Internet usage and penetration is only half of the story in the IoPTS world; device connectivity is the more important statistic. The headline in a recent report reads “Gartner Says 8.4 Billion Connected ‘Things’ Will Be in Use in 2017, Up 31 Percent From 2016” (2017, February 7). This number is forecasted to reach 20.4 billion by 2020 with total spending on endpoints and services to be almost $2 trillion in 2017 (Gartner, 2017).

How will IoPTS affect the workplace? We are just beginning to investigate the impacts; it is a workplace where automation continues to grow rapidly (Corsello, n.d.). Challenges such as retrofitting buildings and homes, data management, and digital security will bring opportunities to those who can provide these types of services (Anderle, 2016). Careers and career paths are already changing as robots and artificial intelligence begin to become realities in the workplace (Ward, 2017). Although “things” will be increasingly providing “services”, the role of “people”, although shifting, will not only continue, but will become more indispensable. Qureshi and Syed (2014) examined the benefits and challenges of robots in the workplace. Future workers in most professions will need to be educated and trained to work in tandem with robots. Not only will people need education and training on the “things” and how to use the “services”, but a recurring theme in this volume is that people will have to take increasing responsibilities in the IoPTS workplace. These responsibilities will be to set their own behavior boundaries in their personal lives and help develop those of others in their organizational lives.

In the pre-Internet workplace, the bilateral psychological contracts summarized employees’ beliefs and discernments regarding the implicit and explicit promises and responsibilities comprising the relationship between employee and organization. They were transactional (focusing on tangible compensation requirements) and relational (involving socioemotional elements, such as trust, fairness, motivation, and commitment) (Robinson, Kraatz, & Rousseau, 1994). A new psychological contract evolved in the 1990s, emanating largely from increasing usage of the Internet and other information and communication technologies. This new psychological contract was based on shorter-term employment, employee responsibility for career development, commitment to the work performed rather than to the employer, and the diminishing importance of hierarchy (Ehrlich, 1994). In the IoPTS workplace, the psychological contract continues to evolve, becoming multifoci (Alcover, Rico, Turnley, & Bolino, 2016). Alcover et al. (2016) proposed that the traditional psychological contract based on a bilateral relationship between the employee and organization had been supplanted by a situation where “employees simultaneously depend on several agents, representing one or more organizations, who assign tasks and goals, supervise work, and provide rewards (or impose sanctions) depending on results” (2016, p. 5). The relationships may be temporary and experienced from different locations, and may include interactions with nonhumans (robots or computers).

We take the multiple-foci psychological contract’s approach (Alcover et al., 2016) one step further, proposing that these nonstandard work arrangements will be the standard work arrangements as the IoPTS becomes increasingly ubiquitous. However, there is a paucity of research on what will be motivating those in the IoPTS workplace to fulfill obligations and commitments in the performance of work and how the necessary levels of trust, security, and privacy critical in the IoPTS workplace will be attained (Eloff et al., 2009). This volume is a collection of conceptual and empirical work, providing a rich resource as well as an agenda for future scholarly endeavors.

Part 1: IoPTS Workplace—People

Part 1 has five chapters exploring ways people and the IoPTS interact in the workplace. In the chapters we are reminded that people are still central in the relationships among “things” and “services” but that the fissure between the positives of efficiency and connectivity and the challenges of disassociation and multiple exchange relationships continues to widen. All the authors make strong arguments that people have a major role and heightened responsibility to lessen this fissure rather than placing their reliance on the “things”.

In Chapter 2, Lisa Nelson points out that despite the many positive effects, there are three prevalent negative effects: 1) increased disassociation among organizational users and between users and the organization, 2) decreased information quality due to inaccuracy and equivocality, and 3) deteriorating social skills because of user overreliance on technology. Nelson then reaches out to the past for guidance from Mary Parker Follett, an insightful management theorist of the early 20th century. Follett’s three most important contributions to organizations—the concepts of circular response, integration, and the law of the situation—are suggested by Nelson as a basis for more humanism in the IoPTS workplace.

In Chapter 3 Constant Beugré argues for the central role of cognition, interpretation, and sense making, all inherent to “people” functionalities. As immense quantities of data are accumulated in the IoPTS, data sense making is necessary if the decision-making process is to have meaning. The mere availability of data is not enough to provide a competitive advantage. What is important is how organizations make sense of the data they collect. As Beugré explains in this chapter, analytics is more a cognitive process than a mere computation of numbers, however accurate they may be. To improve the use of analytics, it is important to combine the use of data with a deep understanding of the domain in which the data are collected and analyzed.

Veronica Godshalk, in Chapter 4, continues with a conceptual warning that the enormity of reach in the IoPTS workplace plants an increasing responsibility on “people” to actively manage this new workplace. She contrasts the contribution that IoPTS can make to maintain work patterns over time and multiple employers and applies the Too Much of a Good Thing (TMGT) effect. The technology associated with IoPTS allows for constant 24/7 accessibility, invasive employer access to employee data and behavioral scans, and even implantable devices—thus the TMGT effect. The IoPTS also may have detrimental effects on individuals through higher stress, more discrimination in hiring, slower career progression, and work–life imbalance. IoPTS needs to be managed properly through individual and organizational support convergence.

Rashimah Rajah and Vivien Lim in Chapter 5 and Kimberly O’Connor and Gordon B. Schmidt in Chapter 6 continue the discussion of people in the IoPTS workplace. Rajah and Lim discuss the results of their empirical work indicating that cyberloafing (using the Internet at the workplace for personal matters) can have positive effects on productivity through the dimension of helping behavior in organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB). The reasoning is that if individuals can mitigate the 24/7 connectivity characteristic of the IoPTS workplace, with downtimes of their choosing for personal usage, productivity will be enhanced. This continues a theme of employee control and responsibility in the IoPTS workplace. In Chapter 5, O’Connor and Schmidt analyze court cases involving employees’ personal use of social media, and they see a trend toward increasing legal protections for employees. They focus on the impact that social media use and the IoPTS has had on certain aspects of the life cycle of employment, such as selection and termination. They examine data privacy protections for workers and discuss the legal issues that organizations may face when monitoring employees or providing them with employer-owned devices. Additionally, they raise questions about the value gained from the use of social media and data monitoring by organizations as they may not be worth the reputational cost. They posit that such data gleaned from IoPTS could be helpful, but there is little research suggesting that the data actually are useful.

Part 2: IoPTS Workplace—Things

Part 2 contains four chapters focusing on how the “things” in the IoPTS affect various aspects of the workplace. The Internet of Things is a world where physical and digital objects are seamlessly connected and integrated into vast networks. These networks are active participants in business processes (Eloff et al., 2009). All the chapters highlight that the Internet of Things is going to give us the most disruption as well as the most opportunity (Burrus, 2014) and that organizational actions can and must be instrumental in building trust, privacy, and security (Eloff et al., 2009).

In Chapter 7 Ulrika H. Westergren, Ted Saarikko, and Tomas Blomquist investigated 21 Swedish firms, all early adopters of IoT. They conclude that in order for firms to successfully implement IoT into organizational processes they have to 1) change their work practices accordingly; 2) make sure that they have access to all needed competencies, be they internal or external; and 3) create an environment of trust that will leverage privacy concerns.

Chapter 8 by Wendy Campbell and Chapter 9 by Irina Nedelcu and Murugan Anandarajan examine security infrastructure. The Campbell chapter explores the impact of IoT on the IT security infrastructure of colleges and universities in Utah. Her findings suggest there is awareness of the challenges and risks of the IoT environment and that strategies have been initiated to mitigate these challenges while also embracing the opportunities. Nedelcu and Anandarajan take a narrower focus by examining specifically the use of smart phones and what motivates users to express intentions to protect their smart phones. Their results indicated that the desire to self-protect is influenced by perceived severity, response efficacy, and response cost. Companies should implement stronger policies, train employees on ways to engage in self-protective behaviors, and work with security organizations to design effective intervention methods. Training should be divided by operating systems because iOS users tend to rely more on the system and less on self-protection than do Android users.

Chapter 10 by Elisabeth E. Bennett highlights another promising transformation in the workplace shaped by the IoT—the shift toward IoPTS as multiple intranets linked to leverage virtual human resource development (VHRD). VHRD emphasizes learning, strategy, and cultural dimensions with a focus on learning, development, and performance improvement. Important to implement is a concentration on the processes of interacting with the IoT such as learning agility and design thinking.

Part 3: IoPTS Workplace—Services

How do we use the technology of IoT in the workplace to be of service? The six chapters in this section offer ways organizations and nations can or do utilize IoPTS. Effectively using IoPTS to provide services requires organizational approaches that singly or in combination proactively minimize risk and increase opportunity throug...