![]()

Although mankind has always shown a huge interest in pictures as is documented in prehistoric cave painting (see e.g. Figure 1.1) and has always used images for different purposes (see e.g. Assmann 2009; Bosinski 2009; Lewis-Williams 2004; Robin 1992), there has been a significant increase in the production, distribution and usage of visual representations in the last few decades.1 The reason for this can easily be detected in the realm of media technology, which has undergone a no less astonishing great leap forward. Most media rely heavily on visual representations.

In particular, the developments in the domain of information technology (IT) have drastically simplified the task of producing and distributing images. An illuminating example is the shift from the verbal to the visual in manuals. Take for instance software; just a few years ago complex programs were delivered with lengthy books explaining their features. Today more and more of these products are accompanied by visual explanations, i.e. by video clips (made accessible on the internet or attached as CD-ROM) instead of a written manual. Thus, moving pictures have taken over the task which the written word formerly fulfilled. This is also true in the scientific domain which is the focus of the following analysis. Here, too, a similar ubiquity of visual representations can be recognised (see e.g. Downes 2012).

This book is a study in the philosophy of science. From this perspective I will tackle the following questions: what scientific images are, which epistemic functions they fulfil in scientific processes (focusing on the empirical sciences), and what their epistemic status is in comparison to other representational means. My aim is twofold, namely to present an investigation into both the concept and the epistemology of visual representations in science. To approach these topics, it might be easiest to start with a brief example.

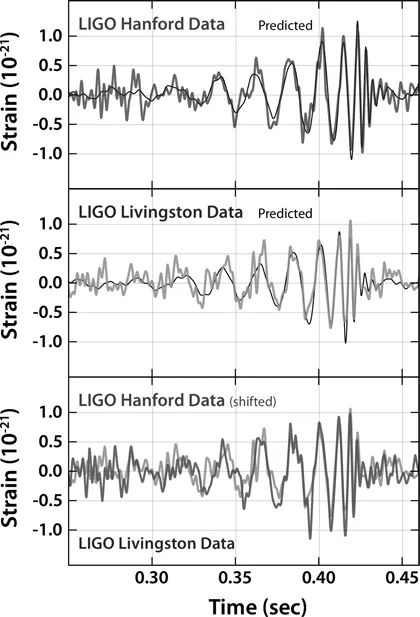

In 2016, physicists involved in the LIGO2 project announced the detection of gravitational waves, i.e. roughly speaking, vibrations of space-time due to the merging of two black holes (see Abbott et al. 2016). The existence of these phenomena was predicted by Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Until the LIGO report, however, no empirical validation of the phenomenon had been achieved. Consequently, their detection meant another significant corroboration of Einstein’s theory and, thus, a major success for the scientists involved in the LIGO project. Part of their reports about this important event consisted of many visual representations, in particular diagrams, one of which is examined as follows.

Figure 1.2 shows the measurement results of two detectors employed in the LIGO collaboration that registered the signal simultaneously on September 14, 2015. The first diagram shows the signal detected at Hanford, Washington, the second the detection at Livingston, Louisiana. Each of them is compared to the curve predicted by Einstein’s theory. The third diagram presents a juxtaposition of the data registered at both Hanford and Livingston; that is, it makes visible the similarity of the data recorded.

Apparently, these images are of special importance to the scientists who have to report their detections. This becomes clear when taking a closer look at B. P. Abbott et al.’s paper (see Abbott et al. 2016), the first official announcement to the scientific community. This paper is 16 pages long; the main part of the announcement comprises roughly eight and a half pages, around two pages are footnotes, and five and a half are used to mention the authors of this article (133 people) and their affiliations. Furthermore, the article contains four complex figures, composed of different diagrams. So approximately half of the pages of the main part are filled by images.

Why are images that important to communicate the event? Is it because what is announced is an optical phenomenon so that it makes sense to show the recipients what it looks like? Of course, this last question is only meant rhetorically. Gravitational waves in space-time, as predicted by Einstein’s theory, are not in any way visible to the human eye. Visual events are only indirectly connected to those events. Moreover, as most of them (fortunately) occur in areas of the universe remote from us, their effects on our planet are very minor in scale, so minute that they are only detectable by instrumental means. Consequently, their detection requires a complex experimental set-up such as that realised by the LIGO collaboration.3 Although the phenomenon they are investigating is not visual in any sense, the authors of this paper thought it relevant to distribute those images attached to their report. What roles do they play? What roles can they play in this context of information distribution? And what functional roles can visual representations generally serve in epistemic processes in science? Should they be replaced by other representational means, such as linguistic expressions? Or can they play a role in such contexts that cannot be transferred to other vehicles of information transmission? These, then, are the central questions that we will investigate in the following analysis.

One major motivation to write this book consists in the astonishing mismatch between the obvious significance of visual representations in scientific practices and their long-lasting neglect in the analyses conducted by philosophers of science. Admittedly, there are many interesting case studies and investigations of visual representations in science,4 but next to none of these studies has ever been compiled by philosophers of science, although theirs would be the traditional place to look for such an analysis when investigating the epistemic status of scientific images. As the example of the detection of gravitational waves shows, the contexts in which those images appear are often related to attempts at information acquisition and distribution, that is, they are epistemic in kind. The philosophy of science explicitly deals with questions of scientific knowledge, its justification and achievements (see e.g. Chalmers 1999; Ladyman 2003).5

The puzzlement about this mismatch between the dominance of the visual in scientific epistemic practices and the apparent lack of interest that philosophers of science have hitherto shown with regard to this topic I share with Laura Perini. Her pioneering analytical work on scientific images has been a major source of inspiration for this book. In her 2005 papers (see Perini 2005a; 2005b; 2005c), she not only makes us aware of the neglect of philosophers to deal with the topic, but also looks for explanatory reasons and an alternative handling of images by seriously taking them into account in the epistemic context.

To put it briefly, her diagnosis of why philosophers of science have not paid proper attention to visual representations rests on the following consideration: research results are presented as arguments in journal articles and the like. Here, scientists try to give reasons for why they think that their results are correct and, thereby, try to convince the members of their community of their findings. But, as Perini points out, it is still unclear what exactly is the kind of contribution that visual representations can make to scientific arguments.

The crux of the matter is that most philosophers think of argumentation as a merely verbal issue. This stance explains why visual representations are excluded as proper components of scientific arguments by these scholars (see Perini 2005b, 262): they simply belong to the wrong kind of representation. Following this line of reasoning, visual representations could only contribute to scientific arguments if they are transferred to the linguistic domain, i.e. by translating their content.6 Scientists, however, do not seem to share this narrow perspective on the assumed cognitive capacities of visual representations. On the contrary, they use images in a variety of ways in their scientific work.

Combining these two observations allows Perini to extract the following characterisation of scientific communication that also highlights the essence of the dilemma:

It is not only this clash of opinions between scientists and philosophers that Perini highlights in her analyses. She also supports the scientists’ assessment of the cognitive role of visualisations. From her point of view, it is essential to take visual representations seriously in epistemic contexts. It is only in this way that philosophers of science can do what they aim to do, namely to understand scientific reasoning.

Although I do not agree with Perini’s solution to the problem (see section 4.1.2 of this book), I am nonetheless sympathetic towards her diagnosis and I fully agree with her demand for a development of a serious epistemological analysis of visual representations in science. Thus, in this book I try to fill the gap that has grown out of the philosophical neglect of this topic.

1.1Topics and methodology

This study aims at an investigation of the epistemology of visual representations in science. Since the role and status of images in scientific reasoning and cognition will be investigated, the focus of this book is on the philosophy of science. Nevertheless, to find answers to some of the above questions, I will make use of insights from other philosophical branches as well, most of all from picture theory and social epistemology.

Contrary to preceding attempts to analyse scientific images presented by scholars from Science and Technology Studies (STS) or the history of science (or the history of art), the focus of my investigation is not on case studies of particular visual techniques, instruments or media. In contrast to such theoretical approaches, I will scrutinise the epistemic particularities of images used in the empirical sciences on a more general level.7 My approach is twofold in this respect. On the one hand, I will analyse the functional roles of visual representations in the scientific processes of acquiring and distributing information. On the other, I will investigate the epistemic status that can be attributed to these images in comparison with other representational means such as linguistic expressions.8

By taking a more detailed look at visual representations in different scientific contexts, I will try to solve the problem pointed out by Perini above; namely why scientists apparently assess the epistemic capacities of images differently in comparison with philosophers of science. Thus, the guiding question will be whether there are epistemic reasons that support and justify the formers’ assessment. The following short guided tour through this book is meant to highlight the line of reasoning by which I will proceed to meet these aims.

It has already been noted that there is an astonishing diversity of visual representations in science. To deal with this finding, we have to start with the question of what the main characteristics of scientific images are (see Chapter 2). Without doubt, all of these visual representations have their particularities, their special advantages and disadvantages as tools in scientific practices. A first question, then, concerns the extension of the term, that is, the scope of the concept of visual representations in science. Here, it will be supposed that scientific images can best be understood as artefacts, that is, as entities intentionally produced by using imaging technologies, instruments, etc. to play a role in scientific cognitive processes. To find out more about their particularities, I will begin my considerations by examining selected paradigmatic instances. Approaching the topic this way will not only allow us to find out how they are produced and, thus, how information is encoded in the visual format, but also what functional roles they are supposed to play in scientific processes and what their advantages and disadvantages as visual tools are when serving these purposes.

A second question connected with a clarification of the concept of scientific images concerns its intension. Despite their di...