- 482 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book develops a new theoretical framework to examine the issues of economic growth and development. Providing analysis of economic dynamics in a competitive economy under government intervention in infrastructure and income distribution, the book develops a unique analytical framework under the influence of traditional neoclassical growth theory. However, in a departure from neoclassical growth theory it examines both the Solow-Swan and the Ramsey growth models, introducing a utility function which treats consumer choices in ways critically different to previous approaches. Using practical examples and models the book demonstrates how this new direction can effectively analyze the key issues of economic growth, in a compact and comprehensive manner.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Economic Growth Theory by Wei-Bin Zhang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Economic Growth and Growth Theory

1.1 Economic Growth

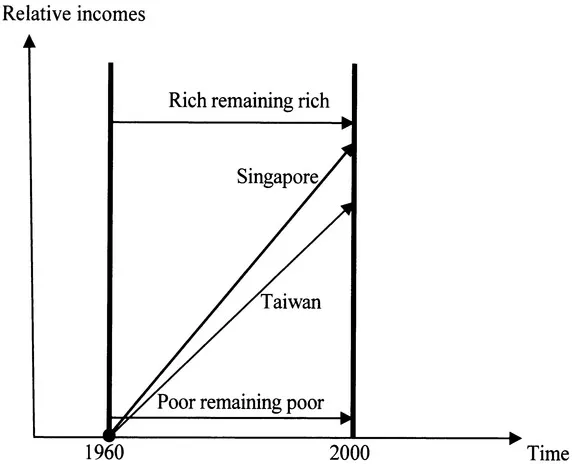

There is one central, simple, and everyday question in economic growth theory: why are some countries/races rich, and others poor? Economic growth theory is concerned with the rise and decline of economic systems. Its central task is to explain economic growth and interdependence between growth and other variables (such as education policy, R&D policy, economic structure, income distribution, saving, work efficiency, population, capital, resources, sexual division of labor and consumption, public goods, and tax structure). How can we account for the phenomenal disparities in living standards around the world? Why are countries, like the United States and Japan, so rich, and why are countries, like Mainland China and Vietnam, so poor? How can one explain the fact that while the average resident of a non-Asian country in 1990 was 72 percent richer than his or her parents were in 1960, the corresponding figure for the average South Korean is no less than 638 percent. Why could East Asian economies, like Japan, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan, have experienced rapid economic growth after the Second World War? We may also ask why some countries have experienced economic declination. Figure 1.1 caricatures changes of incomes per capita in Taiwan and Singapore over 40 years from 1960 to 2000. Over the four decades, some rich countries like the U.S. have remained rich; while some poor economies like Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan had experienced 'economic miracles'.1

The United States experienced an average annual growth rate of 1.75 percent of the real per capita gross domestic product (GDP) over the period from 1870 to 1990. The per capita GDP increased from U.S.S 2244 in 1870 to U.S.$ 18.258 in 1990 (when the U.S. citizens were enjoying the highest level of real per capita GDP in the world), measured in 1985 dollars.2 To maintain sustainable growth, even with a small growth rate on average, means much in the long term. For instance, if the real per capita growth rate was 0.75 percent instead of 1.75 percent, the real per capita GDP would have been changed from $2244 in 1870 to $5519 - rather than U.S.$ 18,258 at the rate of 1.75 percent - in 1990. But if the real per capita growth rate was 2.7 percent instead of 1.7 percent, the real per capita GDP would have been changed from U.S.$ 2244 in 1870 to U.S.$ 60,841 - rather than U.S.$ 18,258 at the rate of 1.7 percent-in 1990. If real income per person in India grows at annual rate of 1.3 percent, it will take about two hundred years for Indian real incomes to reach the current U.S. level. If the average growth rate is about 3 percent, it will take about hundred years for India to equal the current U.S. level of real income per capita. The time will be reduced to 50 years if the average growth rate is increased to 5.5 percent.

Figure 1.1 An Illustration of Cross-Country Economic Growth

Singapore is an interesting case for growth theory. When Singapore attained self-government on June 3, 1959 after nearly 140 years of British colonial rule, it had population of 1.58 million that was growing at the rate of 4 percent annually. The socio-economic environment was not much different from that in the premier cities of most underdeveloped countries. Majority of the Singaporeans merely managed to make a modest living by hard work. Half of the population was living in squatter huts and only 9 percent in public housing. Its per capita GNP in 1960 was 443 U.S. dollars.3 It has almost no natural resources. The independence had put Singapore in a situation that even survival seemed a miracle. But Singapore has achieved more than a survival miracle. The real GDP in 1996 was 16 times more than that in 1965, the year when Singapore attained political independence. On the average, the economy grew by more than 9 percent annually during this period. In 1997, the per capita indigenous Gross National Product was U.S.$36,422. In Table 1.1, we compare some development indicators between Singapore and some countries. The real income differences across countries imply large differences in nutrition, literacy, infant mortality, life expectancy, and other indicators of well-being. Singapore outperformed many highly industrialized economies such as Australia and United Kingdom in terms of real per capita GNP, even though it still lagged behind these countries in terms of some social indicators. Lucas asserted:4 'I do not think it is in any way an exaggeration to refer to this continuing transformation of Korean society as a miracle, or to apply this term to the very similar transformations that are occurring in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Never before have the lives of so many people (63 million in these four areas in 1980) undergone so rapid an improvement over so long a period, nor (with the tragic exception of Hong Kong) is there any sign that this progress is near its end.' The rapid progress was obviously at end soon after Lucas published his article, even though another miracle involved far more people in Mainland China was starting in East Asia.

Table 1.1 International Comparison of Development Indicators in 19955

| GNP per Capita In U.S.$ | Real GDP per Capita (in PPP) | Growth Rate (%) 1985-95 | Literature Rate (%) in 1994 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 22,990 | 22,950 | 4.8 | 92.3 |

| Japan | 39,640 | 22,110 | 2.9 | 99.0 |

| Singapore | 26,730 | 22,770 | 6.2 | 91.0 |

| U.K. | 18,700 | 19,260 | 1.4 | 99.0 |

| U.S.A. | 26,980 | 26,980 | 1.3 | 99.0 |

Kaldor observed a number of stylized facts of the progress of economic growth. These factors include:6

- (1) Per capita output grows over time, and its growth rate does not tend to diminish.

- (2) Capital-worker ratio grows over time.

- (3) The rate of return to capital exhibits almost the same over time.

- (4) The ratio of physical capital to output is nearly invariant over time.

- (5) The shares of labor and physical capital in national income change little over time.

- (6) The growth rate of output per worker differs substantially across countries.

Facts 1, 2, 4, and 5 appear to be held for the long-term data for currently developed economies. It seems that fact 3 should be replaced by the fact that real rate of return to capital tends to fall. In addition to the patterns of economic growth by Kaldor, Kuznets observed other characteristics of modern economic growth.7 According to Kuznets, there are rapid transformations from agriculture to industry to services in association of modern economic growth. In association with rapid economic structural transformations, an economy will also experience rapid urbanization, shifts from home work to employee status, an increasing role for formal education, increased international trade, and a reduced reliance on natural resources. In particular, he held that government plays a significant role in providing institutions and infrastructures in sustaining economic growth and development. We now review some traditional economic growth theories for explaining these phenomena.

1.2 Economic Growth Theory

Natural laws, once discovered, maintain structural stability in the sense that they can be repeated in a predictable way under certain circumstances. Natural laws are invisible and intangible but appear to exist everywhere and always. Newton's laws are valid in a predictable way; so is Einstein's relativity theory. Water boils in the same way in Japan, Sweden, and Australia. Under given conditions it boils at predictable temperatures at standard atmospheric presses. Snow forms much in the same way under similar conditions all over the world. Observations of natural law are reproducible. The regularity of natural laws is characterized by that under the same conditions the same experiments should always give the same results anywhere in the world at any time. Disciplines such as astronomy, chemistry, physics, geology, and biology have developed a robust combination of logical coherence, causal description, explanation, and testability. These disciplines are more or less mutually consistent. For instance, the laws of chemistry are compatible with the laws of physics, even though they are not reducible to them. Chemists do not propose theories that violate the elementary physics principles of the conservation of energy. Instead, they use the principle to make sound inferences about chemical processes. The traditional scientific strategy is to decompose the whole into simpler parts until we can deal with simple parts.

Similar to natural sciences, economics has tried to find simplicity in a complex reality by this strategy. But its success cannot be compared to those enjoyed by natural sciences. Various fields in economics live in isolation from each other. Students trained in one subfield often have not a shared understanding of the fundamentals of the others. When economists from each subfield are busy with pursuit of learning, they do not converge upon a common framework but find themselves in divergent directions. Economists have made various assumptions about the underlying laws of econo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Economic Growth and Growth Theory

- 2 The One-Sector Growth (OSG) Model

- 3 Traditional Growth Theories and the OSG Model

- 4 Some Extensions of the OSG Model

- 5 Income Distribution and Growth

- 6 Structural Changes and Development

- 7 Growth, Unemployment and Welfare

- 8 Learning by Doing, Education and Learning by Leisure

- 9 Research and Learning by Doing

- 10 New Growth Theories and Monopolistic Competition

- 11 Complexity of Economic Growth

- Bibliography

- Index