![]()

1 The Method of Inquiry

Introduction

The state of Texas has built a reputation for itself as the leading producer of crude oil and natural gas in the nation. Advancements in drilling technology like hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” in the state has only helped to further boost its oil and gas production and maintain its lead in energy production among the 50 states. Although fracking, like the electric car, may sound like a new technology to many, it has been present for several decades. It involves the use of horizontal drilling in conjunction with conventional vertical drilling to extract crude oil and gas from thousands of feet below in the sedimentary rocks. The attractiveness of this unconventional drilling practice lies in its ability to efficiently produce oil and gas from potential reserves in sedimentary rocks that were once considered inaccessible. This technology has made a timely comeback when crude oil and gas imports and prices were high in the nation and the federal government remained committed to its goal of energy independence. An added impetus was also a state climate that favored oil and gas drilling.

As fracking proved to be a success in Texas, the big and small oil and gas companies both in and outside the state lost no time in adopting this advanced drilling technology. The improved technology enabled the oil and gas industry to enhance their oil and natural gas production in the state. It prompted the companies to undertake massive exploration and drilling operations within the state and the investments paid off when massive sedimentary formations with potential reserves of oil and natural gas were identified within the state. With the proliferation of fracking within the state, it made gradual inroads into rural and urban communities.

During the period of fracking boom from 2009–2015, numerous rigs dotted the rural and urban landscape in the energy rich shale plays of the state. They served as a constant reminder that oil and natural gas production was taking place even amidst the regular activities of rural and urban life. The busy movements of onsite workers and the truck traffic plying back and forth to the production fields transformed the character of many quiet cities and towns into bustling centers of oil and gas production. The ancillary service industries including hotel, transportation, housing, food and others also received a boost while the state benefited from an increase in revenue from oil and gas production and sale of goods.

Research Focus

Behind the façade of economic gains loomed serious environmental concerns that failed to receive as much attention as the economic gains and rapid strides made toward energy independence. Residents living in rural and urban communities located close to drilling sites or where fracking was conducted within the boundaries of small towns and cities objected to its many negative externalities that were unforeseen at the time of adoption of this technology. It led to individuals’ numerous complaints to the local and state governments that went unheeded. This added to their frustration and opposition to the drilling practice in many parts of the state. With the social outcomes of fracking not being as optimistic as the economic ones, this study has tried to investigate the regulatory and environmental aspects of fracking that have caused much discontent among people who have been adversely affected by this unconventional drilling activity.

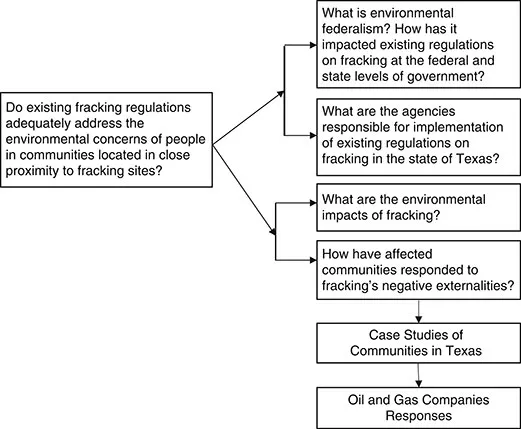

Figure 1.1 The Logic of Inquiry.

The research question that has been posed in the study is: “Do existing fracking regulations adequately address the environmental concerns of people in communities located in close proximity to fracking sites?” To answer this question calls for two things. First, investigation into the regulations on fracking at the federal and state level of government and the agencies responsible for their implementation. Second, a look at some of the environmental impacts of fracking and communities’ responses to it.

The information will offer readers a glimpse into the existing regulations on fracking, create awareness of the environmental impacts of this advanced drilling procedure and enable readers to better understand the needs of individuals and the decisions of local and state governments at the juncture of economic gains and loss in environmental quality. Hopefully such information will help both individuals, decision makers, public administrators and the corporate world to agree on an efficient and effective strategy that will balance public interest with private ones without jeopardizing the prospects of goals of energy independence and expansion of geopolitical influence.

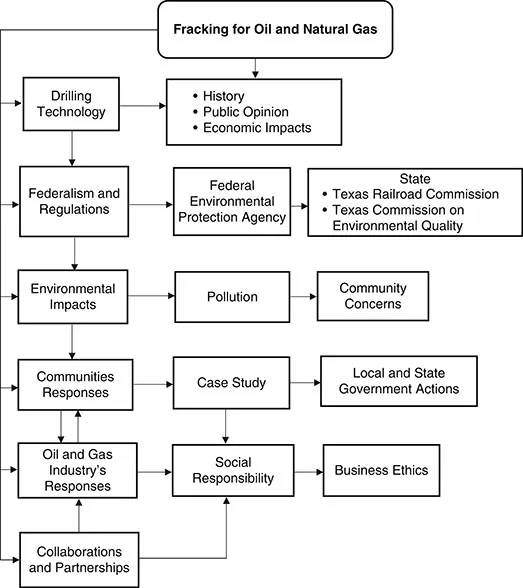

Figure 1.2 A Conceptual Framework of Fracking in Texas.

Sources of Information

In the collection and processing of information for the study, a qualitative research methodology has been used. Its selection can be validated on the grounds of versatility of its various research tools that have proven to be useful in the collection of both primary and secondary data. In the collection of primary data for the case studies, interviews were conducted. Individuals affected by fracking, community leaders, public officials, and other stakeholders were interviewed for the study. In selection of these people of interest, a snowballing approach was used where selection was made possible through a referral process. It helped to identify and include in the sample those individuals who had much information to share based on their personal experiences and or the role they played in community organizations.

The interviews were conducted over the telephone and participation in the study was on a voluntary basis. Each interview lasted approximately 40 minutes. Interviewees were asked various open-ended questions to probe the impacts of fracking on their lives and their involvement in actions, if any, to bring about changes in local policies. Their personal insights into the problem of fracking in local communities were also captured during the interview process. Overall, participants’ inputs into the information seeking process simply added to the robustness of findings that have been reported in the case studies.

In the collection of secondary data, multiple sources were used. They included the websites of government agencies, the oil and gas industry, policy and environmental organizations, peer reviewed articles, newspapers, and even blogs. In retrieval of relevant information, content analysis and keyword searches were frequently used. Even the Google alert system proved very useful. It helped to collect the latest news on fracking that kept pouring into a designated mailbox on a regular basis and which was reviewed from time to time for reference purposes.

Further, in trying to offer a glimpse into residents’ responses to fracking in communities close to fracking sites, a case study approach has been adopted because of the flexibility it affords in the collection and framing of information. As pointed out by Patton (2014), “a qualitative case study seeks to describe that unit in depth and detail, holistically, and in context.” Additionally, a case study helps to present interesting facts and information from a past event or focus on a problem that is being confronted by a community. Whatever may be the issue or the problem, it is the unique aspect of each case that draws public attention and arouses their curiosity on the final outcome. Even various watchdog groups follow the progress of events in a case because of their personal or vested interest in it. The media also intervenes in the publicity of a case using both traditional (newspapers) and non-traditional (social media) modes of communication to evoke responses from people. Nowadays, even a random Google search on the internet on any topic can help to retrieve a plethora of information on various cases that offer noteworthy lessons. These lessons can be on success, failure, sustainability, and avoidance and can also be used as exercises in problem solving by academics or in decision making in various organizations.

Keeping in mind the essential elements of a case study, the cases presented in this book have focused on two things – (a) the externalities from fracking and their consequent impacts on the lives of those people who live at close proximity to drilling sites and (b) communities’ responses to fracking. Through description and narration of details, each case has tried to draw attention to those events that are worthy of consideration in the context of bringing about relevant changes in the existing regulatory framework of the state and local governments.

Understanding Public Policy

We are all familiar with the words “public policy.” All of us have heard endless times that we need to adhere to public policies, irrespective of our personal liking or dissatisfaction with them. Since public policies are inextricably linked to our lives, one needs to be reminded that their design and development is a complex process. Initially, it requires a political will to bring about a change. This is often followed by a chain of actions that require investment of time, resources, stamina, and perseverance to nurture a policy idea from its agenda to an implementation stage. In the journey of a policy idea from its inception to the action stage, its path is riddled with obstacles. The removal of obstacles calls for the involvement of several actors and each plays a unique role in the policy making process.

Focus on Regulatory Policy

Public policy can be classified into various types – regulatory, distributive, and redistributive (Lowi, 1964). Let us take the case of regulatory policy. Its impacts on the practice of fracking in urban and rural communities are considerable in the state of Texas and are the focus of the book. The very word “regulatory” is disliked by most people. Generally, people dislike any kind of restriction that is imposed on their activities. We hate to be told at what speed we should drive our car or where to dump our garbage. It is our independent spirit, disregard of the welfare of others, and selfish interest for profits that make us hate regulations. At the same time, from our innumerable experiences and failure of the market system, we have learned that governmental regulations can only protect us from the unfair trade practices that can deal a heavy blow to our lives and welfare.

Typically, regulatory policies are formulated and implemented to protect and serve the needs of the public and those who are regulated. Even though very few realize the dual purpose of such policies, they are often deemed as obstacles in our path and hated by those whose activities are regulated. Regulations are used by the government as a means to curb the unfair practices of those individuals and companies that render harm to the public and put their lives and welfare at risk. Violation of regulations can be costly, making companies pay millions of dollars as fines and compensations to the victims of unfair trade practices.

The social benefits of regulation far outweigh the economic costs involved in compliance of government-imposed standards. For example, if not for regulations in the Clean Air Act, flaring of waste chemicals like volatile organic compounds such as sulfur dioxide, waste gases, and benzene, a well-known carcinogen, would have remained unchecked from a refinery and chemical plant owned by Shell and its affiliated partnerships. This would have exacerbated toxic air pollution in the area and inflicted serious health damages on people in the surrounding community of Deer Park area near Houston. For the alleged violations of the Clean Air Act in 2013, the company settled with the U.S. Department of Justice and the Environmental Protection Agency to spend at least $115 million on upgrading its facility to curb toxic air pollution and pay $2.6 million as civil penalty (Department of Justice, 2013). Another example that helps to reiterate the importance of regulations is the case of Volkswagen cheating on emission testing in the U.S. The company had installed software to cheat on emission testing in 11 million vehicles that were sold in the U.S. (Gates, Ewing, Russell & Watkins, 2017). If not for existing regulations on emission testing, such a trap would have gone undetected. The Volkswagen cars would have continued to spew tons of harmful pollutants into the air from tailpipes and wiped off some of the gains made in air quality as a result of strict enforcement of emission standards on automobiles.

Regulations have delivered many benefits to the public and the industry and do cost money to both when implemented. The public as taxpayers have to fund the agencies responsible for implementation while the companies have to pay for retro-fittings and investment in new technology that are required by regulations. Many times regulations have saved the public from becoming a victim of unfair trade practices and paying heavily in terms of money or lives and sometimes both as seen in the case of faulty Takata air bags that were installed in Honda, Ford, and other auto manufacturers’ vehicles. When it comes to the environment, even though the public relies more on regulations than on the market to make a transition to renewable energy in the twenty-first century, there seems to be an even split on the issue of whether fewer regulations can protect air and water (Funk & Kennedy, 2017).

In a free enterprise economy, just as too many regulations can be oppressive and are considered unconducive for industrial growth, laxity in regulation and deregulation can be equally worrisome. For example, small oil and gas companies in West Texas availed an exemption that allowed sources that emit less than 25 tons of sulfur dioxide and volatile organic compounds to be exempted from the strict permitting requirements of the Clean Air Act. As per the exemption, these companies were not required to issue public notices and invest in advanced technology to abate air pollution. Unfortunately, the exemption granted in good faith was violated when oilfields released ten million pounds of pollutants into the air in 2016, which posed a serious threat to public health in the surrounding community (Collett, 2017).

Even efforts to minimize regulations and promises of self-policing may spell victory for the oil and gas industry and be well worth the lobbying expenses, but in the long run they do the public little good. People’s lives and welfare are at risk when there is no way for them to find out about hidden dangers lurking close by. In such circumstances, go...