![]()

1 Daudi

To the best of my knowledge, or at least I was told that, I was born on Tuesday the 21st of August 1951. Do you know during that time there was no recording of dates? It was in the afternoon because my middle name is Kiprotich. Yes, that means it was between three p.m. and four p.m. It might be necessary for you to know how the Kipsigis nomenclature works. Yes, the middle name represents time of day so at least the time of birth is always remembered. If it was a little earlier in the day, it could have been Kibet. Or if it was in the morning I would be Kipng’eno, or Kipng’etich, but Kiprotich that means “when the cows are coming back home”. Goats usually come later in the day. Cows come home a little early because there is the milking process. And so my name means I was born when the cows returned to be milked.

Davy was not my first name. Actually I was David. Yes, actually not even David, but I was first Daudi. Yes, we had different names and then eventually I converted the name to be more sophisticated. I decided to call myself Davy. That was there about 1966. This is not unusual. You know in this country people call themselves various names. It is only when they end up having to get a formal identification that they actually settle on something. Davy Kiprotich arap Koech is my full name but then there are also other descriptive names. I am also named after my grandfather. So I am Arap Seng’eret. You see, in between those, there are other names. As I was telling you, you have so many names but at some point you must settle on something. So as is known on record, I am Davy Kiprotich Koech. I dropped the name Arap.

But I was not born Koech. I was born as Daudi Kiprotich but this changed when I had gone through the Kalenjin rite of passage for boys. I acquired my father’s middle name, Kipkoech, after the rite of passage in 1962. Among the Kipsigis, those are my people, the males go through the rites of passage from the ages of ten to 14 years of age. I was one of the youngest to go through the rite of passage because my father was pushing me to go early. In fact, I had to go through the rite of passage before I was even ready. Yes, that one was now in 1962.

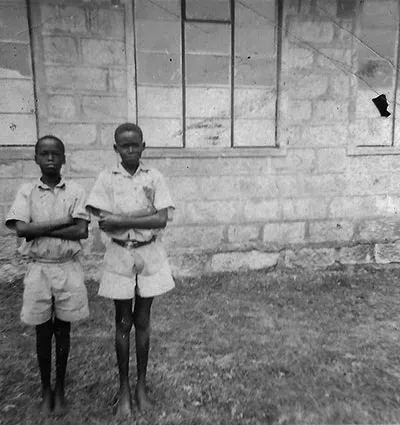

My father was always pushing me to start things early. I started the school at the age of four. I was too young. I had to be taken to school because I could not manage to walk from home to Soliat alone, which was close to 4 km away. So I was taken halfway to school and then from there I would make the rest of the distance on my own. In the evening I used to run back home and an incident happened which is very difficult to forget. I had just been bought a pair of long khaki shorts as part of my school uniform, towards the end of 1955. I went to class one for only one term and then I was promoted to class two in 1956. I was living at Motero village back then. So, at the age of five, before I was due to even go to nursery school, I was promoted to class two at Soliat Primary School.

Figure 1.1 Davy Koech [left] with a classmate in primary school, 1960. [The first photograph in his life. He is nine years old.]

“Soliat”, like the name sounds, is named after a grass. It is a tall grass, which you see in the grasslands. You may have seen in the grasslands that some animals will hide under the grass and so the school was named after this particular type of pasture. This grass grew everywhere at that time because we did not have the problem of today with overgrazing. And so, I was at school, and at ten, maybe 11, in the morning I picked one of the stalks of grass and started to chew on it. You know, the way kids do. Yes, I was exactly five years old and I chewed it but instead of being reprimanded by my teacher, he said, “please don’t do that”. When I continued, he took me by the hand and he was about to cane me when all hell broke loose! I immediately went straight toward the teacher’s index finger, and bit it, leaving a permanent scar. In fact, the finger was disfigured! It was no longer straight. Of course, I was then beaten and so I decided that I was not going to wear those silly pair of shorts that they had made us wear. And I left them at school and walked away from school, heading home.

When I reached home, my mother was there and she then said to me, “Kiprotich …” Actually, when we pronounce our names, the Ki remains silent, so she would say, “Protich.” This is because the Ki was introduced by wazungus to make it more pronounceable. She says to me, “Where is your pair of shorts?” I told her, “They are at the school.” She was annoyed with me. So eventually, at the end of the day my elder sister and brother brought my pair of shorts home. This event made a real change in my life because I had bitten the headmaster’s finger and actually that finger remained disfigured for the rest of his life. I think he passed on recently. When my father returned home, I was not disciplined but he was cross at me and he said, “I understand you. You get very angry very easily.” I had not yet learned to control my emotions. I was still very young anyway. So at the end of the day my sister brought my pair of shorts home and in the village I was the only one, besides my brother, who had a pair of shorts. Others did not have any. So it was privilege. Yes, it was a privilege to own a pair of shorts back then because people had very little.

I come from the Kipsigis sub-tribe. The Kipsigis is the predominant tribe among the Kalenjin-speaking people, about 58 per cent of all the Kalenjins. Both my father and mother were Kalenjin. I have many siblings from two mothers. Christine is the eldest, followed by Elizabeth then Elijah, Paul, me then Musa, Florence, Sarah, Rachel, John, Jane and Solomon. We have middle names that may be difficult to explain here. Elijah is Kiprono, and Paul is Kipkoros. Do you remember I told you about my brother Kipkoros? I follow him. Then my younger brother, Musa, follows me. They have all gone to their own houses and they are married. In fact, I realized recently I have so many nieces and nephews and I don’t know all of them so very soon now I will have them come now to my house for a family gathering.

My father passed on in 1988 at the age of 92 years. I believe my father passed on because of shock. My father died, I think I would say organ failure, because he was okay until one day when he was going home he met some guy on the road, that winding road walking home. He met a certain person from home who says, “Hi mzee, how are you?” My father replies, “It’s okay … yes yes yes.” And then the fellow asks, “How was the funeral?” My father said, “Which funeral?” “Your sister?” And so this is how he came to know that his sister had passed on. His sister Opot Tolony was staying very far from our home where most of the relatives were, in the Waldai area. You see that is where she was married and that’s where she was staying but she and my father were very close. So he didn’t know that she had passed on. Actually I cannot understand. So he started feeling unwell as a result of the shock from the news that she had passed and then he started having multiple organ failure, and then six weeks later on he passed.

He was a strong man and healthy throughout his life. He never went to hospital even a single day. No, not even for a single day he had never been to hospital. When we realized that the kidneys weren’t working because he could not pass urine, and we knew there was a problem, we took him to the hospital. The kidneys were partially working and he had a lot of uric acid in the blood and urea … and then the kidneys failed. Yes, this all happened within six weeks. And so he passed on at the age of 92 and this was in 1988.

My mother passed on in 2004 when she was 86 years old. She was slightly diabetic but she didn’t pass on because of complications of diabetics. She woke up from her bed to go to the bathroom and then she slipped, and broke her hip. She came to stay at my house in Kericho to recover, but she had a clot, an embolism in her lungs, and died.

![]()

2 Colonial administration

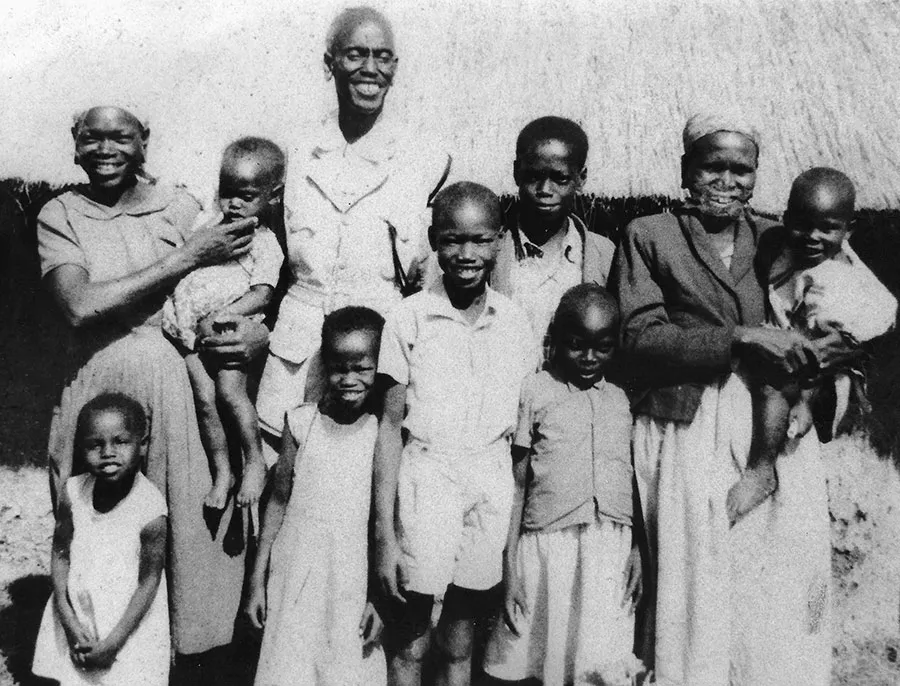

By the time my father, Samuel Kipkoech arap Mitei, dropped out of school because of distance, he knew how to read and how to write. I think that gave him an advantage and it is why he was selected to be a border guard under the colonial administration. I think during the First World War he was able to see what other people were doing, he was exposed to new things, even though he was just a cattle rustler. You see, he was too young to join the First World War. So during that particular time he was asked to go and collect cattle. These young men were the ones looking for cows and so on to bring them to a certain locality where they could be collected and then processed for meat to feed the soldiers. That used to happen during the First World War, and the Second World War the same thing occurred. People, like my father, used to collect cattle from farms, then they are taken to be slaughtered, and then the meat is transported to feed the soldiers in the war. So although my father during the First World War was too young to go to war, he was not too young to be sent as an errand boy. So he was sent to go and collect the cattle and then push them back to a particular place, the Boma. This is what we call the place in Kiswahili. Boma means a corral. Yes, where all the cattle are held and then from there they are taken to be slaughtered and then the meat transported. Yes, the meat could go to various parts of the world. So that was the role of my father during the First World War.

Figure 2.1 Koech’s family, with father in uniform.

Yes, at the beginning of the First World War he was just about 16 or 17 years old, because he was born in 1896, and at that time they thought this slightly too young. They could not be trained to handle guns or something like that. Then in 1925, after the war, the colonial government was now doing the boundary demarcation of the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. The colonial government identified my father to participate in the demarcation of boundaries, the area largely between the Kipsigis and the Luo. So my father was doing the boundary between Kisumu and Kericho district from a place called Chemase, on top of Kisumu up in the hill, all the way up to Sondu. So every two steps they put a sisal, another sisal, another sisal, and my father was negotiating with another person, Mzee Oliech, who was identified among the Luo community to participate in the boundary demarcation. They had to agree on the boundary. So they did this between 1925 and 1932. My father worked almost for free, on a pro bono basis, between 1925 until 1932.

And those boundaries have never changed until even today.1 There has never been any border dispute until today, except one minor change made by a constitutional amendment in 1964, which allowed the Luo to follow the Nyando River further to the east where the headwaters are. So instead of the boundaries going straight from one point, it starts beyond the river and then makes a small peninsular, and then back again. That was the only constitutional amendment of the provinces, which was done by Jaramogi Oginga Odinga when he was the Vice-President and the Minister for Home Affairs.

My father became a border guard before he married my mother. And then he was a chief. My mother was involved in church activities. She was a lay pastor, which meant there was some restriction within the village. Because of my father’s discipline with public administration and my mother’s role in the church, we were not involved in some of those cultural activities that could be seen as destructive by the colonialists.

Soon after the border work my father was appointed as a Chief under the colonial administration. His main role was purely administrative matters, like settling conflicts within his area of jurisdiction, and they were involved in collecting taxes. We used to have what we call a hut tax, I think it was one shilling.2 For every hut that you see, the British collected a tax on it. In fact, until recently they used to have this hut tax. As Chief, he was involved in making sure that people lived in harmony, people cultivated their farms. The Chief was everything in the society. He was like the CEO of a village and in charge of the government, what we called “On His Majesty Service” (OHMS) until 1952 under King George. OHMS was even written on the vehicles, either On His Majesty Service or On Her Majesty Service, something like that.

The chiefs of those days were fairly powerful. But my father did not need to exercise that authority because of the kind of people he was dealing with. They were just fellows from home, cattle thieves, and so he had to return the cattle which had been stolen from the Luos to Kipsigis or vice versa. Sometimes it was people who were drunk and disorderly, even managing them, and things like that. Basically he was responsible for keeping order. Order in any system and making sure government regulations were obeyed. If it was time for planting, he must ensure there was planting. So from 1932 all the way until just one year before independence in 1962 when he retired from the public service. Yes he worked for about 37 years for the public service. He got his pension, which was 1080 KES at that time, for all those years of service. I remember he was very angry when he retired. He was given his pension and his pension was 1080 KES total. Can you imagine – 1080 KES for having worked in the government for 37 years from, 1925 until 1962?!

I remember him talking about independence. He said, “You know what? I am happy we are getting independence.” He retired in 1961, one year before independence. Having worked for so many years for the colonial state, he believed the transition to independence would turn out well. He felt deeply about it because he was part of the group that was organizing, on a diplomatic front, to bring independence to Kenya, telling people not to resort to arms. Telling people not to engage in violence. He believed to do it correctly, to succeed from the British, there should not be any bloodshed. So he was part of that group, the prime movers demanding settlement by peace and not killing each other. Yes. He didn’t want violence because he said, “It will stiffen the heart of these imperialists.” It would stiffen their hearts so it was good to approach it with some level of wisdom and caution.

He was one of the greatest influences in my life. For example, in regards to planning. I would see him often because at home in the village he had his own house, the main house, because he wanted to wake up in the morning to go to work but he didn’t want to disturb anyone in the family. So he had, we call it singiroino [/a gazebo/], like a small building outside. In most homes, most of our rural homes, they have one, it is an outside building. A small outside building where you could meet with friends, you could meet with people, and so on like a gazebo or a banda. Yes. So he used to stay there and I used to sleep with him. He didn’t want to wake up any of his wives when he was ready to go to work and did not want to disturb anyone. So in the evening, I would watch him – before he sleeps he would fetch his clothes for the morning, and he made sure everything was ready, setting them by the bedside. Of course we are dealing with little huts. The whole room could be a couple metres at most, but he would organize it. And he would say to me:

“Listen, see what I am doing? What am I doing?”

“You have prepared your clothes, father.”

“Am I wearing them now?”

I say, “No. You are wearing them in the morning.”

“Precisely. What else have you seen?”

“I have seen you have organized your sufuria [/pan/] there for tea.”

He used to love tea, and a small cup with some milk. Then he would prepare the fire to be lit in the morning. You know the three-legged stones for cooking? Yes, and he would say to me,

What you are going to do tomorrow, plan it today. What you are going to do next week, plan it this week. What you are going to do next year, plan it this year. What you are going to do the next decade, plan it this decade. So he said, son, plan. Plan. Plan. You will not succeed by waking up in the morning you don’t even know what is where. Before you go to bed you must know what you are going to wear tomorrow.

Although there was no wardrobe to select from so that you cannot get confused as to what to wear! You wear the same thing every day. This lesson is ingrained in me until today. It is not possible for me to sleep without knowing what I will wear tomorrow. It ...