Three assumptions guide our approach to understanding psychiatric and substance abuse treatment programs and their outcomes. First, in order to examine the influence of treatment programs on patients’ adaptation, we need systematic ways to measure the key aspects of the treatment process. Although most behavioral scientists endorse the idea that both personal and environmental factors determine behavior, evaluation researchers have typically conceptualized the treatment program as a “black box” intervening between patient or staff inputs and outcomes. Thus, these programs often are assessed only in terms of broad categories, such as the level of care provided or whether they accept patients with severe psychiatric disorders. To enrich understanding of these settings, we describe some useful ways to measure program characteristics; these measures enable us to identify specific aspects of treatment programs and to analyze their influence on patients’ in-program and community adaptation.

Our second assumption is that although treatment programs for psychiatric and substance abuse patients are diverse, a common conceptual framework can be used to evaluate such programs, and doing so has several advantages. The framework allows us, for example, to identify similar processes occurring in different types of programs and to specify the extent of environmental change an individual experiences when moving from one type of setting to another, such as from a hospital to a community facility.

Our third assumption is that more emphasis should be placed on the process of matching personal and program factors and on the connections between person-environment congruence and patients’ outcomes. To understand the influence of treatment programs more fully, we need to examine the selection processes that affect how patients are matched to programs. We also need to focus on how treatment environments vary in their impact on patients who differ in their level of impairment and the chronicity and severity of their disorders. Although researchers have recognized the complexity of person-environment transactions, empirical work has not adequately reflected the multicausal, interrelated nature of the processes involved.

Conceptual Model

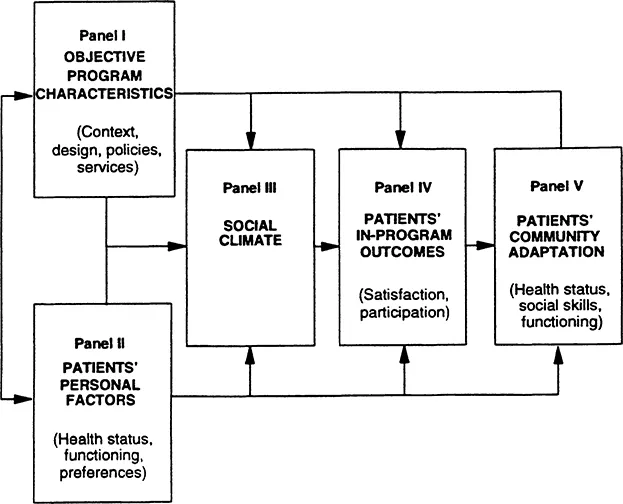

The conceptual model shown in figure 1.1 follows these guidelines and provides a framework for examining treatment programs and how they and their patients mutually influence each other. In this model, the connection between the objective characteristics of the program (panel I), patients’ personal characteristics (panel II), and patients’ adaptation in the community (panel V), is mediated by the program social climate (panel III) and by patients’ in-program outcomes (panel IV). The model specifies the domains of variables that should be included in a comprehensive evaluation.

The objective characteristics of the program (panel I) include the program’s institutional context, physical design, policies and services, and the aggregate characteristics of the patients and staff. These four sets of objective environmental factors combine to influence the quality of the program culture or social climate (panel III). The social climate is part of the environmental system, but we place it in a separate panel to highlight its special status. The social climate is in part an outgrowth of objective environmental factors and also mediates their impact on patients’ functioning. In addition, social climate can be assessed at both the program and the individual level.

Personal factors (panel II) encompass an individual’s sociodemo-graphic characteristics and such personal resources as health and cognitive status, and chronicity and severity of functional impairment. They also include an individual’s preferences and expectations for specific characteristics of treatment programs. The environmental and personal systems influence each other through selection and allocation processes. For example, most programs select new patients on the basis of personal and psychiatric impairment criteria. Similarly, most patients have some choice about the program they enter.

FIGURE 1.1.

A Model of the Relationships between Program and Personal Factors and Patients’ Outcomes

Both personal and environmental factors affect patients’ in-program outcomes, such as their satisfaction, self-confidence, interpersonal behavior, and program participation (panel IV). In turn, in-program outcomes influence such indices of community adaptation as patients’ health status, social and work skills, and psychosocial functioning (panel V). For example, on-site counseling and self-help groups and policies that enhance patients’ decisionmaking (panel I) may contribute to a cohesive and self-directed social climate (panel III). In such a setting, a new patient may be more likely to develop supportive relationships with other patients and join a counseling group (panel IV) and, ultimately, to show better community adaptation (panel V).

The model shows that patients’ adaptation is also affected directly by stable personal factors. For example, patients who have less severe symptoms when they enter a program are likely to have less severe symptoms a year later. Treatment programs may have some direct effects as well, as when an individual experiences better outcome because of the quality of treatment provided in a setting.

Finally, the model depicts the ongoing interplay between individuals and their treatment environment. Patients who voice a preference for more self-direction in their daily activities may help initiate more flexible policies (a change in the environmental system). Patients who participate more actively in psychotherapy or self-help groups may experience improved self-confidence (a change in the personal system). More generally, individual outcomes contribute to defining the environmental system; for example, when the in-program behavioral outcomes for all patients in a program are considered together, they constitute one aspect of the suprapersonal environment.

The model incorporates the characteristics of staff (panel I) and how staff influence the social climate and patients’ in-program and community adaptation. We focus almost entirely on patients’ outcomes here, but the basic model can be extended to encompass the health care work environment and it’s influence on the treatment environment and staff members’ morale and performance (Moos and Schaefer, 1987).

From a broader perspective, environmental factors external to the program profoundly affect patients’ community adaptation. Hospital and community programs typically constitute only one time-limited aspect of patients’ lives; accordingly, their influence may be shortlived. To understand the determinants of patients’ psychosocial functioning in the community, we need to consider their family and work settings and their broader life circumstances (Moos, Finney, and Cronkite, 1990).

In the next sections, we describe two main lines of work that led us to focus on the characteristics of treatment programs: historical analyses and descriptive studies of how treatment environments alter patients’ in-program symptoms and behavior, and comparative evaluations that illustrate how different programs affect patients’ longer-term adaptation. In essence, this body of research suggests that characteristics of treatment programs, such as those included in panels I and III of figure 1.1, influence patients’ in-program (panel IV) and community (panel V) outcomes.

Historical Background and Descriptive Studies

In modern times, the idea that treatment environments can change the patients and staff who live and work in them can be traced to Philippe Pinel, who in 1792 removed the chains and shackles from the inmates of two insane asylums in Paris. Most of the patients stopped being violent once they were free to move around. Pinel pointed out that people normally react to being restrained or tied with fear, anger, and an attempt to escape. Pinel applied “moral treatment,” and assumed that the social or treatment environment, especially tolerant and accepting attitudes, setting examples of appropriate behavior, humani-tarianism, and loving care, affects recovery from mental illness.

I saw a great number of maniacs assembled together and submitted to a regular system of discipline. Their disorders presented an endless variety of character; but their . .. disorders were marshalled into order and harmony. I then discovered that insanity was curable in many instances by mildness of treatment and attention to the mind exclusively.... I saw with wonder the resources of nature when left to herself or skillfully assisted in her efforts.... Attention to these principles of moral treatment alone will frequently not only lay the foundation of, but complete, a cure; while neglect of them may exasperate each succeeding paroxysm, till, at length, the disease becomes established, continued in its form and incurable. (Pinel, 1806)

The Rise of Moral Treatment

In 1806 the Quaker William Tuke established the York Retreat in England, emphasizing an atmosphere of kindness and consideration, meaningful employment of time, regular exercise, a family environment, and the treatment of patients as guests. The Quakers brought moral treatment to America, and Charles Dickens (1842) noted the results in a lively account of his visit to the Institution of South Boston, later known as the Boston State Hospital.

The State Hospital for the insane is admirably conducted on ... enlightened principles of conciliation and kindness.. . . Every patient in this asylum sits down to dinner every day with a knife and fork... at every meal moral influence alone restrains the more violent among them from cutting the throats of the rest; but the effect of that influence is reduced to an absolute certainty and is found, even as a means of restraint, to say nothing of it as a means of cure, a hundred times more efficacious than all the straight-waistcoats, fetters and handcuffs, that ignorance, prejudice, and cruelty have manufactured since the creation of the world----Every patient is as freely trusted with the tools of his trade as if he were a sane man.... For amusement, they walk, run, fish, paint, read and ride out to take the air in carriages provided for the purpose. .. . The irritability which otherwise would be expended on their own flesh, clothes and furniture is dissipated in these pursuits. They are cheerful, tranquil and healthy... . Immense politeness and good breeding are observed throughout, they all take their tone from the doctor. ... It is obvious that one great feature of this system is the inculcation and encouragement even among such unhappy persons, of a decent self-respect. (105-11)

Grob’s (1966) history of the Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts, which was established in 1830, documents the recognition of the importance of moral treatment and the patients’ social environment (see also Kennard, 1983), He points out that Samuel Woodward, the first superintendent, thought that mental illness resulted from impaired sensory mechanisms: “If the physician could manipulate the environment he could thereby provide the patient with new and different stimuli. Thus older and undesirable patterns and associations would be broken or modified and new and more desirable ones substituted in their place” (53).

Woodward believed that mental illness was an outgrowth of detrimental social and cultural factors. The hospital implemented moral therapy, which consisted of a regular daily schedule and individualized care, including occupational therapy, physical exercise, religious services, and activities and games. Staff members were trained to treat patients with kindness and respect; physical violence and restraint were discouraged. The provision of moral treatment assumed that a healthy psychological environment could kindle renewed hope and cure individual patients. It implied that an appropriate social milieu could eliminate undesirable patient characteristics that had been acquired because of “improper living in an abnormal environment” (Grob, 1966, 66).

Although it is impossible to compare patients at Worcester in the 1830s and 1840s with patients today, the supportive structured climate of moral treatment may have been quite successful. Of more than 2,200 patients who were discharged from Worcester between 1833 and 1846, almost 1,200 or 54 percent were judged recovered. Moreover, in a long-term follow-up of almost 1,000 such recovered patients, in which information about the patient was obtained from family members, friends, employers, and clergy, nearly 58 percent were not readmitted to hospital and did not have a relapse (Grob, 1980).

Hospital Social Structure and Patients1 Symptoms

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed a retreat from the principles of social treatment and increasing reliance on custodialism and physical restraint. During the 1950s and 1960s, however, theorists and clinicians again focused on the importance of the treatment environment. There was yet another reevaluation of the traditional disease model and its assumption that psychological disturbance resides in the individual alone. Hartmann’s (1951) and Erikson’s (1950) theoretical contributions reflected renewed interest in individual development and the link between external reality and perceptual and cognitive functions.

This focus was applied to try to understand the social structure and processes of psychiatric programs, which constitute the “reality” for hospitalized patients. Stanton and Schwartz (1954) and Caudill (1958) observed the importance of hospital social structure in facilitating or hindering treatment goals. Stanton and Schwartz’s contribution revealed that patients’ symptoms could be understood as a result of the informal organization of the hospital, that is, that the “environment may cause a symptom” (343). They found, for example, that hyperactive patients were typically the focus of disagreement between two staff members who themselves were seldom aware of this disagreement. The patient’s hyperactivity often ceased abruptly when the staff members were able to discuss their disagreement.

Stanton and Schwartz also noted that a patient’s dissociation may be quite reasonable in the face of certain social situations; for example, when two staff members strongly disagree about how to manage a patient, that patient may also be of a “divided mind.” When staff disagreement or the “split in the social field” is resolved, the patient’s dissociation usually subsides. Stanton and Schwartz (1954) conclude that “profound and dramatic changes such as observed in shock therapy ... are no more profound and no more rapid than the changes produced ... by bringing about a particular change in the patient’s social field” (364). In addition, these authors showed how aspects of the hospital social environment, such as fiscal constraints stemming from financial pressure, may elicit staff conflict and confusion, which, in turn, generates low staff morale and collective disturbances among patients.

Caudill (1958) independently substantiated many of Stanton and Schwartz’s conclusions. In a clinical example, he revealed how the social structure of a psychiatric unit influenced a patient’s behavior. Caudill showed how the patient’s excited and disturbed behavior was due to his personal relationships with his therapist and with other patients. The therapist’s interest in the patient was influenced by other staff members’ attitudes, and the course of the patient’s illness was closely associated with the hospital’s therapeutic and administrative routines. Caudill (1958) concluded that “a patient’s pattern of behavior cannot be sufficiently apprehended within the usual meaning of terms such as ‘symptom’ or ‘defense,’ but must also be conceptualized as an adaptation to the relatively circumscribed situation in which he is placed” (63). In another example, Stotland and Kobler (1965) show how a suicide epidemic in a hospital was directly related to changes in the hospital’s financial and social structure and to resultant changes in staff morale, attitudes, and expectations of patient improvement.

Custodial Institutions

Although the development of moral treatment temporarily spawned a caring and humane social environment, as mental hospitals grew in size and complexity the emphasis on enlightened social treatment receded and institutions became more structured and custodial. The growing belief that immutable genetic and constitutional factors were the primary causes of mental illness contributed to this trend.

These changes led to the concept of “total institutions,” which Goffman (1961) described as assuming absolute control over the life of people who reside in them. Total institutions break down barriers that ordinarily separate different domains of an individual’s life, such as places of home, work, and recreation. In total institutions, all aspects of the residents’ lives are conducted i...