Female genital mutilation/cutting: the context

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also called female genital cutting (FGC), female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) or ritual female genital modification/alteration, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the partial or total removal of the external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons (WHO, 2008). Readers unfamiliar with the subject might consider FGM/C a limited and ‘foreign’ issue. However, recent estimates indicate that at least 200 million girls and women have been subjected to the practice in 30 countries around the world, in communities with different religions and cultures (Unicef, 2016). To fully understand such prevalence data, it is worth comparing such data with the global prevalence of more familiar health conditions such as HIV, chronic hepatitis C or diabetes, reported respectively as 36.7 million (WHO, 2015), 130–150 million (WHO, 2016b) and 422 million people worldwide (WHO, 2016a). Highly FGM/C prevalent areas can be found in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and South America. In any given country the prevalence may vary depending on the region. With migration, FGM/C also occurs in high-income countries (WHO, 2008; Unicef, 2016). In Europe there are around 500,000 FGM/C-affected women (Unicef, 2016).

FGM/C is a human rights and public health issue with complex historical, anthropological, sociocultural, legal, political and economic implications. It is a deeply rooted traditional rite of passage practiced among Muslim, Christian and Animist ethnic groups (WHO, 2008).

From a health perspective, the practice can affect women’s and girls’ psychophysical health negatively, with possible infectious, uro-gynaecological, obstetric, sexual and psychological complications (Berg et al., 2014a; Berg et al., 2014b; WHO, 2016c). There are many research gaps when it comes to the effective care of women and girls living with the complications of FGM/C. One of these concerns treatments for sexual dysfunction after FGM/C as well as the sexual anatomy, physiology and function of these women and girls (Abdulcadir et al., 2015c). A lack of evidence often adds up to preconceptions and limited education of healthcare professionals on these topics, which are rarely included in their training curricula (Abdulcadir et al., 2016a).

One of the main misconceptions shared by both FGM/C practicing and non-practicing communities is that female sexual organs, and in particular the clitoris, are removed through genital cutting (Public Policy Advisory Network on Female Genital Surgeries in Africa, 2012). Many practicing communities presume that FGM/C prevents women from being hypersexual, promiscuous and unfaithful; this is one of the leading cultural reasons why FGM/C persists (Jirovsky, 2014). Non-practicing communities think that FGM/C compromises women’s sexual function always and irremediably (Catania et al., 2007; Jirovsky, 2014). Even the current WHO official classification of FGM/C (see Table 1.1) reports that some forms of female genital mutilation involve the total removal of the clitoris (WHO, 2008).

Table 1.1 Classification of FGM/C.2007 (WHO, 2008).

| Type 1.1: Partial or total removal of the clitoris* and/or the prepuce (cli tori d ectomy) |

| Type Ia: Removal of the clitoral hood or prepuce only |

| Type Ib: Removal of the clitoris* with the prepuce |

| Type II: Partial or total removal of the clitoris* and the labia minora.with or without excision of the labia majora (excision) |

| Type IIa: Removal of the labia minora only |

| Type IIb: Partial or total removal of the clitoris* and the labia minora |

| Type IIc: Partial or total removal of the clitoris*, the labia minora and the labia majora |

| Type III: Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora. with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation) |

| Type IIa: Removal and appositioning of the labia minora |

| Type IIb: Removal and appositioning of the labia majora |

| Type IV: Unclassified |

| All other harmful procedures to the female genitaliafor non-medical purposes, for example, pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization |

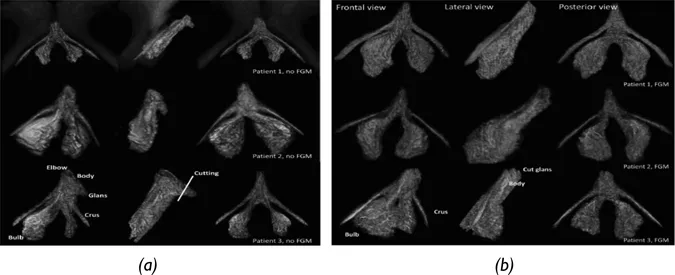

However, as hypothesized in the past (Catania et al., 2007; Pauls, 2015) and then confirmed by a pelvic MRI study we published in 2016, it is the glans of the clitoris (the external visible part of the organ) which is excised in some forms of FGM/C. The majority of the organ (made up of the body and the crura), together with other female erectile structures, the bulbs and the corpus spongiosum of the urethra, remain intact and can be functional (Figure 1.1) (Abdulcadir et al., 2016a). This is why healthy women with FGM/C, with no long-term complications, can experience normal sexual function (Abdulcadir et al., 2016a; Paterson, 2012), and women who suffer from psychosexual complications can be offered treatment.

Evidence and knowledge about female sexual and reproductive health after FGM/C are important to improve and promote women’s and couples’ health-care; correctly and honestly inform women, girls and men; and dispel myths, fears and false beliefs which negatively affect women’s and girls’ lives, and FGM/C prevention and healthcare.

Women’s sexual function, with or without FGM/C, is influenced by multiple factors and can be improved by education and information (Nazarpour et al., 2016; Jawed-Wessel et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2017). Healthcare professionals have a key role to play. However, caregivers, including gynaecologists, may lack knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the vulva and its sexual organs and sexual health (Andrikopoulou et al., 2013). Women are often exposed to popular sociocultural misconceptions instead of appropriate health education on subjects such as physiologically variant appearances of the vulva, orgasm and sexual function. This happens in high- and low-/middle-income countries, where non-therapeutic genital practices like both FGM/C and female genital cosmetic surgeries (FGCS) exist (Creighton, 2014).

Figure 1.1 3-D MRI reconstruction of the clitoris in three women without (a) and with (b) FGM/C involving the excision of the clitoris.

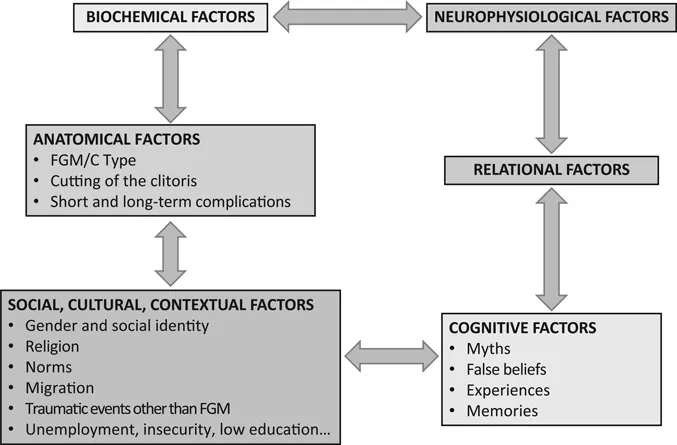

The available evidence indicates that women having undergone genital cutting report more dyspareunia and less sexual desire, orgasm and satisfaction (Berg et al., 2014b). Such evidence is limited and also has important methodological limitations. For instance, all types of FGM/C, with or without cutting the clitoris, have been investigated together. In addition, the questionnaires used were not validated in the population included, or did not cover all the factors that can influence sexual function (Abdulcadir et al., 2015c). Some of the multiple interacting factors in sexual function of women with FGM/C are specifically related to the genital cutting procedure, with its potential physical and mental consequences (Figure 1.2). Anatomically, the FGM/C damage/injury varies depending on types and complications. Some FGM/C types involve the cutting of the clitoris; others consist in the narrowing of the vaginal orifice, and others again (like pricking or nicking) do not remove any genital tissue (WHO, 2008).

Psychosexual function after female genital mutilation/cutting

Figure 1.2 Factors influencing women’s sexuality after FGM/C.

From an anatomical point of view, the type and severity of the genital cutting together with its eventual complications (Kimani et al., 2016) can affect sexual anatomy and function in various ways (Paterson, 2012). Perineal obstetric trauma; recurrent vaginal and urinary infections including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID); superficial dyspareunia due to mechanical obstacles represented by FGM/C type III (infibulation); vulvar bridles, scarring consequences, keloids and cysts; granulomas and neuromas of the clitoris can be responsible for pain or dyspareunia and negatively affect sexual functioning. Women with FGM/C, especially Types II and III, have been found to be at increased risk of negative obstetric outcomes (Kimani et al., 2016), with a higher risk of prolonged second-stage labour, obstructed labour, episiotomy, perineal tears and third-degree tears (Balogun et al., 2013; Banks et al., 2006; Berg and Underland, 2013; Paliwal et al., 2014; Belihu et al., 2016), conditions that may be responsible for pelvic floor and sexual morbidity. Recurrent or chronic genito-urinary infections can also possibly worsen women’s sexual well-being (Kimani et al., 2016). However, the current evidence on this specific topic is not conclusive. A systematic review could not find any significant association between genito-urinary infections (except from bacterial vaginosis) and FGM/C (Berg et al., 2014b).

FGM/C Type III narrows the vaginal orifice by the apposition of the labia minora or majora (WHO, 2008). This narrowing can vary depending on the severity of the infibulation and can be responsible for superficial dyspareunia, difficult or impossible penetration and recurrent perineal trauma with formation of perineal scar tissue (Abdulcadir et al., 2016b). Vulvar bridles can also cause pain or bleeding during sexual intercourse (Abdulcadir et al., 2016b). Epidermal cysts, frequently located near the clitoris, are a common consequence of FGM/C (Rouzi, 2010). Often asymptomatic, they can reach a large size, become inflamed or abscessed and then painful. When located just upon the clitoris and surgically removed, women can experience a worse sexual function after the cyst is removed (Thabet and Thabet, 2003). This is because during sexual intercourse prior to surgery, the cyst presses on and stimulates the clitoris, facilitating orgasm (Paterson, 2012). Women and their partners have to be informed about this as well as the location of the clitoris after cystectomy.

Post-traumatic clitoral neuroma is another FGM/C-related condition that can be responsible for chronic neuropathic vulvar pain and superficial dyspareunia. It is probably an under-reported and under-diagnosed condition, and the evidence regarding its prevalence, symptoms, management and recurrence rate is limited (Abdulcadir et al., 2017b). Few case reports and a small retrospective case series have been published. Successful treatment has been the surgical excision of the neuroma (Abdulcadir et al., 2017b; Abdulcadir et al., 2012b; Abdulcadir et al., 2015b; Fernandez-Aguilar and Noel, 2003; Schiotz et al., 2012). As in other anatomic sites, a clitoral neuroma can be asymptomatic or, less frequently, painful. When painful, it is associated with allodynia and hyper-algesia, functional impairment and psychological distress, with a severe impact on the quality of life and relationship (Abdulcadir et al., 2017b; Abdulcadir et al., 2012b; Abdulcadir et al., 2015b; Fernandez-Aguilar and Noel, 2003; Schiotz et al., 2012).

From a psychological point of view, genital cutting is reported to be associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety (Berg et al., 2010; Knipscheer et al., 2015; Vloeberghs et al., 2012). However, the evidence on FGM/C-related mental health effects is quite limited (Berg et al., 2010). FGM/C is a taboo subject among the communities practicing it, making it difficult to discuss it openly. In addition, the expression, acceptance and understanding of psychological symptoms varies depending on the culture of the group investigated. Not undergoing FGM/C where it is highly prevalent, can lead to stigma and social exclusion, possibly causing mental problems as well (Berg et al., 2010; Knipscheer et al., 2015).

The diversity in the interpretation and coping with the event of FGM/C and the level of ability to recall seem fundamental for experiencing psychopathology (Knipscheer et al., 2015). There is diversity in the experience, memory, values and issues associated with FGM/C (see Jordal, and Johanson in this volume), which can be performed when less than one year old, before menarche or during adulthood, by a traditional circumciser with no analgesia or by a physician performing antisepsis and anaesthesia. The feelings, experiences and memories referred to by women during and after this rite of passage vary from bravery, honour, social and family acceptance, social positive feedback and success, to suffering, fear, betrayal, incomprehension and powerlessness (Tumiati, 2016). Many women consider their genital cutting as normal and not sickening, or positively as a sign of beauty, female identity and pureness. Others are not aware of their past FGM/C. Some have developed effective coping strategies with the past traumatic event while others do suffer from mental problems directly linked to the FGM/C or, more frequently, as a result of multiple coexisting conditions and past experiences. FGM/C-affected migrant women, for instance, are likely to have experienced other traumatic events in the past such as war, child abuse, forced marriage, rape, political violence and violence during migration (Antonetti Ndiaye et al., 2015). In an ongoing cross-sectional study on pelvic floor symptoms that we are conducting at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the Geneva University Hospitals, 45% of the 60 women already included referred to having experienced past traumatic events other than FGM/C a...