![]()

1 Introduction

A political and linguistic history of Hong Kong

Introduction to the chapter

On September 22, 2014, I stood in the mall of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) watching thousands of secondary and university students gather to begin a week-long class boycott to protest the decision by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC) of The People’s Republic of China (PRC) to delay the popular vote for Hong Kong’s next Chief Executive from 2017, as previously promised, to an indefinite time in the future. By sheer coincidence, this event occurred on the day marking the beginning of the research that has resulted in this book. Hours before, I had submitted a request to the mass mailing system at CUHK to release an online survey to students about language attitudes in Hong Kong. The survey was released at CUHK a few days later, at the beginning of what has come to be known as the Umbrella Movement, when the week-long class boycott evolved into a sit-in protest in front of Hong Kong’s government headquarters. The Umbrella Movement lasted for seventy-nine days, and while it did not change the NPCSC’s decision, the movement has had far-reaching influence on politics as well as on attitudes to language and cultural identification in Hong Kong.

This is the focus of this book – the impact of politics, and particularly, grassroots political movements for independence and democracy on language and identity in Hong Kong. The research documented in this book grew from a desire to understand attitudes towards language in Hong Kong, and specifically, attitudes towards Hong Kong English (HKE), the local variety of English emerging in the region. As the Umbrella Movement unfolded, it became clear that the political landscape of Hong Kong was changing and that Hong Kong’s students were spearheading this political change. With the changing political landscape, the focus of this book changed. What was meant to be a one-year survey of attitudes towards HKE among university students grew into a four-year project tracking attitudes and researching how politics were impacting language and identity in Hong Kong.

This book explores the question(s) of language and identity against a backdrop of politics among the first generation of postcolonial Hong Kongers, millennials largely born after 1997, when after 145 years of British colonial rule, Hong Kong was handed over to the PRC. It focuses on questions about the status of English – the colonial language imposed on Hong Kong by Britain starting in 1842 – as well as Cantonese, the regional variety of Chinese spoken in Hong Kong. Cantonese has always been the carrier of a local identity, particularly in contrast to English, the language of the colonizers. The book examines the status of English – whether it has become a language of – in contrast to language in – Hong Kong, and whether, and for whom, it serves as a marker of a Hong Kong identity, particularly in contrast to a mainland Chinese identity. The status of Putonghua, a language of Hong Kong after the return to PRC rule in 1997, is also examined. The book also examines attitudes towards HKE as a marker of a local, Hong Kong identity. At the heart of the book lies the question of whether and how politics influences identity, language attitudes, and language use. This is particularly relevant to Hong Kong, where language has always played a key role in the construction of a local identity, first in juxtaposition to the British colonizers and now in contrast to mainland Chinese.

Essentially, this book attempts to answer three main questions:

• Are politics influencing identities in Hong Kong?

• Are politics influencing attitudes towards language(s) and varieties in Hong Kong?

• Which language(s)/variety(s) reflect a local, Hong Kong identity – being a ‘Hong Konger’?

Answers to these questions have implications beyond Hong Kong; they help us to understand how political events can shape language use and language identification, and how this can occur in relatively short periods of time rather than unfolding over decades or centuries. As such, this book presents the first study to track real time language attitude changes against a divisive political landscape. It is also the most comprehensive study of language attitudes in Hong Kong to date, taking place over four years with over 1600 participants. The use of both survey and interview data presents a multifaceted portrait of language change in progress, providing a more nuanced and complex view of language and identity than has previously been presented. The focus on the status of HKE in view of attitudes towards Cantonese, English, and Putonghua also provides deeper analysis of the linguistic complexity of Hong Kong; it can be argued that one cannot understand attitudes towards HKE without fully understanding the status and use of English in Hong Kong. The book also presents a complex examination of language attitudes in Hong Kong by focusing not only on the what of language attitudes, but also the question of for whom, through an analysis of language attitudes by gender, age, identity, and speaking HKE. Language attitudes are not monolithic within any given population; rather, different demographic groups may hold different – and conflicting – language attitudes; they may also respond differently to the political atmosphere. This book attempts to tease out which language attitudes exist in Hong Kong for English, Cantonese, and Putonghua, as well as for different varieties of English, including HKE, and for whom these attitudes exist and why.

The primary data for the study is drawn from university students for the first three years of the study; in the final year of the study, 2017, data is also included from secondary students, also politically active in Hong Kong, as well as people who are in the workforce or retired. This expansion of the population from which the research is drawn also contributes to a deeper understanding of language attitudes in Hong Kong today. In short, this book presents the most comprehensive and detailed study on language attitudes to date, drawing on findings from five different but interrelated areas to present a unified and multifaceted portrait of language attitudes in Hong Kong today.

Overview of this book

This study is longitudinal, from September 2014 until August 2017, with data collection spanning a four-year period. At the same time, it is a close-up snapshot of language change in progress in terms of attitudes and ideologies, language identification, and language use. The data collection and analysis of the data is set against a backdrop of an increasingly politically divided Hong Kong; as such, the study attempts to capture a real-time portrait of how language and politics interplay both within and across time. In trying to capture the complex relationship playing out with language and politics at a particularly heightened and sensitive political time in Hong Kong, multiple dimensions of language attitudes and ideologies are explored, starting with the construction of a Hong Kong identity or identities, a key factor to the analyses of language attitudes in this book. The book examines the characteristics of three cultural identities – Hong Konger, Hong Kong Chinese, and Chinese – to try to understand the relationship among age, gender, schooling, language, and identity as well as how identity marking changes across time. Of interest is whether the current political conflicts with mainland China are strengthening the local Hong Kong identity (e.g., Hong Konger). This is explored in detail in Chapter 3.

The book also explores attitudes to the three languages of Hong Kong – English, Cantonese, and Putonghua – and the linguistic representation of identity. It examines language ownership in relation to the status of English in Hong Kong, and whether it has become a language of rather than a language in Hong Kong as well as how Putonghua, the national language of China, is viewed, particularly in juxtaposition to Cantonese, the local/regional variety of Chinese spoken by most Hong Kong people. The status of English in Hong Kong is also examined in relation to Cantonese and Putonghua. In addition, the research examines the construction of a monolingual and multilingual identity, and ideologies about mono- and multilingualism in relation to these three languages. Of interest is how participants view themselves as native speakers and whether English is viewed as a native language in Hong Kong and why. This is explored in Chapter 4.

Hong Kong is not only multilingual, it is also multilectal. British English (BrE) the variety of English most entrenched in Hong Kong due to colonial rule, has historically been held in prestige in this territory. The study examines whether BrE still holds this status for the first generation of postcolonial Hong Kongers, or whether the affinity with this variety has diminished over the past twenty years since handover. Given the current political situation in Hong Kong, it is also possible that nostalgia for British colonial rule has resulted in BrE still being held in high regard. It also examines whether American English (AmE), increasingly popular globally due to the domination of American mass media (Bielby & Harrington, 2008; Holt & Perren, 2009; Hopper, 2007), has gained popularity in Hong Kong. The status of the local (endormative) variety of English in Hong Kong, Hong Kong English (HKE) is also explored in relation to the exonormative (external) varieties of AmE and BrE, particularly as a marker of a local identity. The relationship between gender and identity and attitudes towards varieties of English is also examined, as are ideologies about monolectalism and multilectalism. This is explored in detail in Chapter 5.

The key focus of the book, however, is on HKE, the local variety of English in Hong Kong. A key question the book seeks to answer is whether the political situation in Hong Kong appears to be strengthening the use of HKE as an identity marker and which factors impact attitudes towards HKE. This is explored through a variety of questions and analyses which seek to examine relationships among speaking HKE, and accepting and wanting to speak it, as well as age, identity, and gender. The key focus in this chapter is to examine whether and how attitudes towards HKE are shifting across the four years of the study, and for whom these attitudes are shifting, and why. This is discussed in view of the political changes and grassroots movements that have taken place during the time of the study, spearheaded largely by the young generation of Hong Kongers, the main participants in the current research. This is examined in Chapter 6. The features of HKE – which linguistic features make this variety different or unique from other varieties of English – are also examined, as well as attitudes towards different features of HKE. Ideologies about the features of HKE are examined, particularly in relation to which features are viewed as symbolic of (e.g., ‘owned’) by HKE in contrast to those that are viewed negatively as representing ‘errors’ in a speaker’s English. The relationship between different types of features and standard versus local language ideologies are also explored. This is examined in Chapter 7. Chapter 8 sums up the various strands of research and provides an overview of the status of English in Hong Kong today.

In the remainder of this introductory chapter, the political and linguistic history of Hong Kong will be presented as well as an overview of recent political events in Hong Kong, as they background the study. In the subsequent chapter (Chapter 2), an overview of the theoretical frameworks and concepts employed in this study, along with a synthesis of research findings on language attitudes and identity in Hong Kong, is presented. Chapter 2 concludes with a discussion of the methodology for the research carried out in this book.

A political and linguistic history of Hong Kong

This section first provides an overview of the demographic and linguistic profiles of both the PRC as well as Hong Kong to foreground the ensuring discussion of language and politics in Hong Kong. While Hong Kong is a part of the PRC, the PRC and Hong Kong have different linguistic profiles due to both historical events and geography. It is necessary to clarify these at the outset.

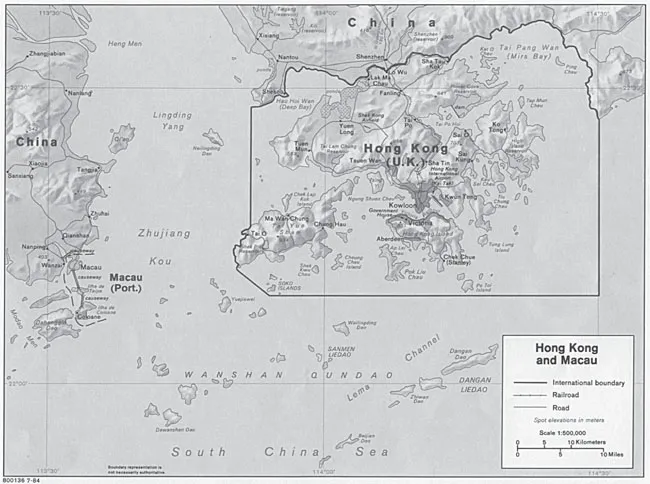

The PRC has twenty-two provinces, four municipalities (city-level governments such as Beijing and Shanghai), five autonomous regions (provinces that have high populations of ethnic minorities; these regions are semi-autonomous in governance and include Tibet, Xinjiang Uyghur, and Inner Mongolia), and two Special Administrative Regions, or SARs. Macau and Hong Kong, both former European colonies, are SARs. Hong Kong was returned to the PRC from British colonial rule in 1997 and Macau from Portuguese rule in 1999. As SARs, Macau and Hong Kong enjoy the highest degree of autonomy of any type of province or territory. The official name for Hong Kong is the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, or HKSAR. Hong Kong has its own flag, passport, national anthem, and constitution, called The Basic Law; The Basic Law grants Hong Kong autonomous rule (e.g., ‘One Country, Two Systems’) for fifty years after the handover, until 2047.

Hong Kong is situated in the southern region of the PRC, on the South China Sea, and shares a land border with Guangdong Province to the north. It is roughly 1106.4 square kilometers in size, a relatively small region of China given that the land size of the PRC is 9.597 million square kilometers. The population of Hong Kong is estimated at 7.4 million; the population of the entire PRC, including Hong Kong, is 1.4 billion, the largest of any country in the world. Ninety-one percent of the population in the PRC belongs to the Han Chinese ethnic group, with the remaining 9% comprising fifty-five different ethnic minority groups, including the Tibetan, Zhuang, Huis, and Uyghurs (Sawe, 2016). Hong Kong’s population is 92% Han Chinese, with the remaining 8% belonging to a variety of ethnic groups, including other Chinese, as well as Indonesian, Pakistani, Filipino, French, British, American, and Australian.

There are 275 indigenous languages of China. Mandarin Chinese, China’s national language, is the most widely spoken. It is estimated to have over one billion speakers in China alone, with a total of 1.1 million speakers worldwide (Chinese, Mandarin, n. d.). The PRC established Mandarin Chinese as its national language in 1912 after the Qing Dynasty was overthrown to promote national unity through a unified linguistic identity. It is based on northern Mandarin Chinese and primarily the Beijing dialect of Mandarin Chinese. It is commonly referred to as Putonghua, or ‘common language’. Of the other 274 languages, 126 languages are currently under threat with a further 32 close to extinction, largely due to the Chinese government’s promotion of Mandarin Chinese (Wade, 2012). The written language of mainland China is simplified Chinese, a written version of Mandarin Chinese.

Before colonization by the British in 1842, Hong Kong was a region of southern China, part of Guangdong (often called Canton) providence of Imperial China. The language of this region was Gwóngdūng wá or Cantonese. Hong Kong Island was ceded to Great Britain by the Qing Dynasty of Imperial China in 1842 in the Treaty of Nanking after the latter’s loss in the first Opium War (also called the First Anglo-Chinese War), which lasted from 1839 until 1842. The Second Opium War (or Second Anglo-Chinese War) erupted between Great Britain and Imperial China in 1856, lasting until 1860. As a result of China’s loss in the second war, the peninsula of Kowloon was ceded to Great Britain in 1860 in the Treaty of Beijing. In 1898, Great Britain secured a 99-year lease of an area referred to as the New Territories as well as Hong Kong’s 235 islands. The picture below shows a map of colonial Hong Kong.

Prior to the Opium Wars, Hong Kong Island was relatively unpopulated. Parts of Hong Kong were settled by two indigenous groups, the Punti (from around 1000AD), and the Hakka, who arrived in the area around 300 years ago (Fat, 2005). When the British took control of Hong Kong Island in 1842, they established it as a free port, resulting in a significant increase in the Hong Kong population through immigration from other regions of China (Bolton, 2003). Bolton (2003) places the population of Hong Kong Island at between 5,000 and 20,000 between 1842 and 1845, growing to 40,000 in 1853 and 120,000 in the early 1860s. Immigration was largely from other southern Chinese provinces, including Guangdong province, where Gwóngdūng wá (Cantonese) was the regional language. As a result of this immigration, which increased significantly during and after the Chinese Civil War in 1949, Cantonese gradually replaced Hakka and Punti as the primary language of Hong Kong; today there are very few speakers of these languages remaining in Hong Kong (Fat, 2005). In fact, a recent large-scale survey found that only 0.9% of the respondents listed Hakka as a mother tongue, and only 1.9% stated they spoke Hakka with their family (Bacon-Shone, Bolton, & Luke, 2015). Cantonese is widely spoken in southern China, Hong Kong, and Macau as well as in many Chinese expatriate communities around the world, with an estimated 62 million speakers worldwide (Chinese, Yue, n. d.). It is the mother tongue of 88.1% of Hong Kong’s population whereas Putonghua is the mother tongue of 3.9%, followed by other Chinese dialects (3.7%), English (1.4%), and other languages (Thematic Household Survey Report No. 59, 2016). The written language of Hong Kong is traditional Chinese; traditional written Chinese is also used in Taiwan and Macau, while simplified Chinese is used in the PRC, Malaysia, and Singapore. As the term implies, traditional written Chinese employs the original traditional characters that have evolved across time while simplified Chinese, introduced in the PRC in late 19th century to increase literary rates in China, is a simpler form of the traditional characters. Like simplified Chinese, traditional Chinese is based on Mandarin Chinese rather than on Cantonese. A common assumption is that Cantonese does not have a written equivalent or unique characters; however, as Snow (2008) states, written Cantonese – based on spoken Cantonese – does exist and is becoming more frequent in usage, particularly in informal writing contexts.

The first official language of Hong Kong was English, established under British colonization in 1842, with continued status as an official language after postcolonial rule; as such, it is the longest serving official language in Hong Kong. Cantonese, the most widely spoken language in Hong Kong, has a relatively short history as an official language, only gaining official status in 1974. The third language of Hong Kong is Mandarin Chinese, introduced after the handover to PRC. Hong Kong also has two official written languages, English and traditional written Chinese.

As noted above, Cantonese did not attain official language status until 1974, even though it is the most widely used language in the territory. Prior to 1974, Hong Kong was considered to have a diglossic linguistic situation, with Cantonese the ‘low’ language, the language of the home and social sphere, while English was the ‘high’ language of law, te...