1 The Law of the Sea regime and the transformation of sovereign disputes in the South China Sea

The main argument of this book is that the evolving contours of China’s South China Sea policy are sculpted by two major factors: (1) the changing dynamics of the Law of the Sea regime; and (2) shifting geopolitics in the region. While the question of how geopolitics influences China’s policy towards the South China Sea and Chinese foreign policy in general has been extensively addressed in the literature, little has been said about the profound impact of the dynamics in the LOS regime in shaping China’s South China Sea policy.

In this book, I attribute the distinctive path of China’s approach to the South China Sea dispute to a unique factor – the law of the sea as “rules of the road” in the ocean. More specifically, I argue that in the post-World War II era, a series of legal breakthroughs in the LOS regime set forth a movement of “enclosure of the ocean” which greatly intensified and complicated conflicts of maritime interests in many areas across the world, especially in semi-enclosed seas like the South China Sea. In the South China Sea case, this movement, galvanized by the establishment of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, transformed the South China Sea dispute from a zero-sum game with clearly defined boundaries into a multi-issue, multi-dimensional, non-zero-sum game with a new parameter of policy options that goes beyond conventional wisdom of managing territorial disputes – confrontation, delay and compromise. It is within this context that significant changes have gradually unfolded in China’s policy towards the South China Sea over the course of time.

Examining the influence of the international maritime regime on China’s evolving policy towards the South China Sea touches upon several important theoretical questions. What is a regime? What does the LOS regime look like? Why does it matter? How is the LOS regime restructuring the South China Sea dispute possible in theory? What roles can the LOS regime play in shaping and reshaping China’s policy towards the South China Sea dispute? This chapter will clarify these questions by building upon constructivist work on the conceptualization of “international regimes” and “sovereignty”.

The evolving Law of the Sea (LOS) regime

The concept of regime in International Relations (IR)

Regime is quite an amorphous entity. The concept of regime emerged in the common parlance of International Relations (IR) in the 1970s. John Ruggie was one of the first IR scholars to advocate the concept of regime. He defines regime as “a set of mutual expectations, rules and regulations, plans, organizational energies and financial commitments, which have been accepted by a group of States.”1 Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye define regime as “sets of governing arrangements” that include “networks of rules, norms, and procedures that regularize behavior and control its effects.”2 Ernst Haas argues that a regime encompasses a mutually coherent set of procedures, rules, and norms.3 The definition formulated by Stephen Krasner remains the standard formulation: “Regimes can be defined as sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations.”4

Nearly four decades have passed since students of International Relations began to ask questions about “international regimes.” Earlier debates focused on the theoretical usefulness and analytical importance of the concept of “regime,” with the more substantive questions that define the regime-analytical research agenda continuing to expand and count among the major foci of IR scholarship.5 The central question to be answered in this regard is why and how regimes or institutions matter.6 What accounts for the emergence of instances of rule-based cooperation in the international system? How do international regimes and institutions affect the behavior of state and non-state actors in the issue areas for which they have been created?7

Neoliberalism and constructivism are two major schools of thought in IR that take regime seriously. Analyses of neoliberal theories suggest that regimes or institutions may have a significant impact in a highly complex world in which ad hoc, individualistic calculations of interest could not possibly provide the necessary level of coordination.8 These theories start from a conventionally rationalist perspective, a world of sovereign states seeking to maximize their interest and power, and they argue that international politics is not always a zero-sum game; rather, states in many situations have mutual interests and regimes assume an influential role in helping states to coordinate their behavior so that they may realize common interests, avoid collectively suboptimal outcomes and achieve desired outcomes in particular issue areas.9 In addition, states are shown to have an interest in maintaining existing regimes even when the factors that brought them into being are no longer extant.10

The constructivist approaches represent a sociological turn in the research paradigm of IR scholarship. IR constructivists have developed a more robust and complex understanding of international regimes. Constructivists are critical of the rationalist assumptions prevalent in mainstream theories of international politics, whether of neoliberal or realist provenance. These scholars problematize states’ identities and interests which are treated as exogenously given by rationalist theorists. They point out that by black-boxing the processes which produce the self-understandings of particular states (i.e., their identities) as well as the objectives which they pursue in their foreign policy (i.e., what they perceive to be in their interests), a significant source of variation in international behavior and outcomes is ignored and ipso facto trivialized.

Consequently, constructivist work features attempts to unlock the black box that is the formation process of states’ interests and preferences. Constructivist theory argues that actors’ perception and interpretation of international problems and their preferences and interests are, in part, produced by their causal and normative beliefs which, in turn, are considered partially independent of actors’ material environment (e.g., the distribution of power and wealth).11 To constructivists, it is misleading to regard actors’ preferences as something that is simply “given”; rather, preferences are to be seen and to be treated analytically as contingent upon how actors understand the natural and social world.12 Therefore, constructivists treat international regimes as inter-subjective socially constructed environments in which states interact and constantly (re)shape their perception of interests, preferences and identities, thus stressing the analytical power of knowledge, ideas and norms as explanatory variables.

Constructivists argue that the power of norms and ideas as pillars of international regimes runs much deeper than might appear at first glance. Norms and ideas not only inform states of cause-effect relationships which derive authority from the shared consensus of recognized elites, but provide “compelling ethical or moral motivations for action,”13 or what some constructivists call the “logic of appropriateness.”14 It is the normative structure and corresponding practices that provide “a condition of the possibility” of individual choice. In this sense, constructivists emphasize not only regulative but also the constitutive and ontological nature of international regimes or institutions, making regular reference to such fundamental regimes or institutions of international society as sovereignty, diplomacy, and international law.15 “These institutions constitute state actors as subjects of international life in the sense that they make meaningful interaction by the latter possible.”16 For instance, the norms and rules that make up the regime of sovereignty define inter-subjectively the responsibilities and rights of each member of the international system.17

Moreover, constructivists emphasize that in the dynamic, socially constructed environment of each individual international regime, static actors are conscious role-players who through dense interactions reach and renew an inter-subjective consensus of shared identity and convergent expectations concerning the right forms of conduct as well as inappropriate behavior in circumscribed situations. Together these regimes weave a “web of meaning” in the daily operation of international relations.18 In other words, norms and rules emerging out of international regimes are not objectively influencing the behavior of member states by affecting their calculations of interests; rather they achieve this goal through influence at a more fundamental and inter-subjective level: they define the self-understanding of states (“who am I?”) and prescribe rules of the game (“what is appropriate/legitimate for me to do?”).19

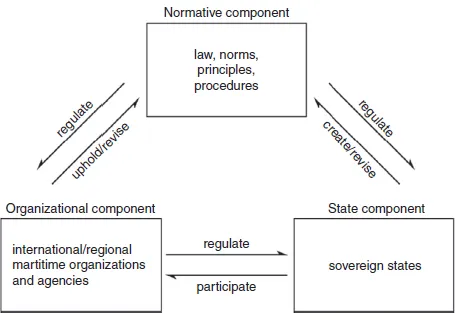

The aforementioned theories advanced by neoliberals and constructivists provide the theoretical foundation for conceptualizing the LOS regime and the roles the regime can play in shaping and reshaping China’s perception and behavior in the South China Sea dispute. As we will see below, the ocean regime, as a social normative environment in which both states and non-states actors engage and interact, is governed by laws, norms and principles that define appropriate, legitimate and meaningful state behavior.

Defining the Law of the Sea regime

The LOS regime is an evolving entity that has existed throughout the history of the use of the ocean by human beings. For centuries it remained in a pristine state and governed the vast oceans, based on a very limited number of norms, the predominant norm being what Haas called “maximum open access”: outside the territorial sea (a narrow strip, usually 3 nautical miles along a nation’s coast), any state could do anything.20 This situation was fundamentally changed by the convening of three UN conferences on the Law of the Sea, thanks to a host of developments concurrently sweeping economic, political and technological arenas in the wake of the end of the World War II. In Chapter 3, the history of the LOS regime will be briefly reviewed so as to provide a background and a starting point for analysis. Suffice it to say that the three UN conferences on the LOS rewrote a new order for the world’s oceans, which is crystallized in the form of the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea, approved in 1982.

Since the PRC officially joined the LOS regime during the preparatory stage of the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) in 1971, discussion of the LOS regime in this book is mainly focused on the period after China’s entry, drawing on the pre-entry period when necessary. What does the LOS regime look like in the post-China-entry period? Drawing on the neoliberal and constructivist theories of international regimes reviewed earlier, this book defines the LOS regime as an evolving entity consisting of three basic elements. Figure 1.1 is an illustration of the LOS regime.

Figure 1.1 Composition of the evolving LOS regime

The normative component: law, norms, principles, procedures and practices

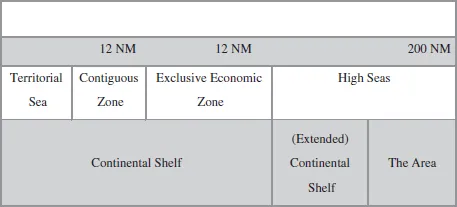

In the category of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, regulations, rights, duties and decision-making procedures, the LOS Convention is considered the “Constitution for the Oceans,” replacing the old law of the sea loosely bound by a few simple rules such as the freedom of the high seas.21 As the core component of the LOS regime, it brings legal breakthroughs to many fronts in the maritime domain, and provides a comprehensive, internally cohesive, legal framework for ocean governance. The Convention establishes five major zones for the world seas, each governed by a very specific set of rules and regulations: (1) the Territorial Seas and Contiguous Zones; (2) the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); (3) the Continental Shelf (CS); (4) the High Seas; and (5) the Area (see Figure 1.2). The Convention develops new legal concepts, principles, and obligations that are now in everyday use and revised the content of many old concepts including, inter alia, common heritage of mankind (CHM), freedom of navigation (FON), provisional arrangement and Dispute Settlement. In particular, the concepts of EEZ and CS have been influential in reshaping China’s legal position on its sovereignty in the South China Sea.

Figure 1.2 Zoning system of the world’s oceans

In addition to the LOS Convention and general principles of international law, there exist a number of maritime treaties, agreements, and other legal undertakings that also have a bearing on ocean governance. Examples include the 1973 Convention on the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, bilateral or multilateral maritime boundary agreements, and those dealing with matters such as access to ports, fishing rights, and so on.22

Also falling into this category is customary international law expressed in general state practices and ...