![]()

1

The Co-evolution of Innovation and Inequality

Mario Scerri, Maria Clara Couto Soares and Rasigan Maharajh

Empirical evidence consistently confirms the relevance of science, technology and innovation in advancing economic development (OECD 1992, amongst others). The analysis of the distributive effects of innovation in the circuits of production, distribution, consumption, and waste management, however, remains largely underdetermined. The complex relationship between inequality, innovation systems and development therefore provides scholars with major opportunities to contribute new insights into an important intellectual domain. The analysis of economic systems through an innovation systems lens has opened up the theoretical space for the analysis of the co-evolution of economic systems and society and of the multiplex causalities of the various interlinked sub-systems. The understanding of the dynamic inter-relations between innovation systems and inequality constitutes a formidable challenge given its complexity, contestation and interdisciplinary character. However, despite the magnitude of the task, a better understanding of the relationship between innovation systems and inequality allows for the evaluation of different options for configuring technological and institutional change and for opening up the possibility for policies that may promote development alternatives which normatively aspire towards greater equality and social cohesion. This book is driven by the imperative shared by both the academic and policy communities to seek to improve our collective understanding of these issues. The book adopts the broad version of the national systems of innovation (NSI) approach to analyse the relations between the innovation systems of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries and inequality, proceeding from a co-evolutionary perspective.

The early works on the systems of innovation approach to the analysis of economic dynamics date back to the 1980s (Freeman 1982a, 1982b; Freeman and Lundvall 1988). Since then the SI approach has been increasingly used to analyse processes of acquisition, use and diffusion of innovations besides orienting policy recommendations in both more developed and developing countries. The initial attempts to present a countervailing theory to the neoclassical orthodoxy were based on a narrow approach to the analysis of innovation systems, with a specific focus on research and development and on organisations directly connected to science and technology. While the narrow approach is still adopted in innovation system literature, the eventual broadening of the understanding of innovation systems and the convergence of the innovation systems approach with the Latin American structuralist approach to development economics (see Cassiolato and Lastres 2008) has brought in a greater analytical and normative capacity to the analysis of national systems of innovation. This broader approach incorporates governmental policies, social institutions, financing organisations, and all other agents and elements that affect the acquisition, use and dissemination of innovations. This approach also includes informal institutions, as established routines and practices which, through processes of socialisation and internalisation, govern social, economic and political interactions. It is this broad perspective which is particularly important to the subject addressed by the book, since it allows a better understanding of how the innovation process takes place and how it is linked with local specificities and distributional issues (see Cassiolato et al. 2008).

An important contribution of the broad approach to the analysis of innovation systems is the recognition of the importance of the socio-economic and political context in which the system is embedded, due to its influence on the configuration of the capabilities of organisations, regions and countries for developing, disseminating and using innovations. In this approach, innovation is considered as deeply dependent on the local specificities of social, political and economic relations, being therefore directly affected by both history and the particular institutional context of countries or regions where it occurs. Therefore innovation and learning reflect the combination of prevailing institutions and the socio-economic structures. The extension of the definition of institutions to include formal institutions not directly connected to science and technology and even further to informal institutions as established forms of routines, practices and interpersonal relations allows for an integrated approach to the analysis of the sources of enduring patterns of inequalities of various forms.

Before we proceed further, however, we need to expand on the rationale for the inclusion of the question of inequality in this series of studies of the various aspects of national systems of innovation in the BRICS countries. This is a legitimate query since in some respects the problem of inequality is substantively different from the other issues addressed in this series. The relationships between the national system of innovation and the state, finance, the small and medium enterprise sector, and transnational corporations and foreign direct investment are immediately apparent and self-evident as relationships between formal institutions. The phenomenon of inequality, in terms of its root causes and effects, is usually seen to belong more to the area of social, rather than economic, studies, even though the degrees of inequality are usually estimated using economic measures. Marxian analysis is, of course, the one main exception to this rather generalised statement, given its direct focus on the economic sources of class divisions and inequality and the innovation systems approach is in its way similar to a refined Marxian approach in its consideration of the totality of the phenomenon and its multidimensional relationship with the economy. This is enabled by the extension of the definition of the economy under this approach beyond the neoclassical reductionist version and by its erosion of the misleading distinction between the ‘economic’ and the ‘social’ spheres.

The detrimental effects of inequality are usually seen in terms of their impact on social stability and on the value system of the democratic ideal. We therefore need to see why the issue of inequality, measured in various ways, should be included as a legitimate component of this series of studies on the various aspects of the BRICS systems of innovation. One reason for inclusion is the empirical evidence that this group of countries experience high levels of inequality as an outcome of their currently pursued developmental trajectories. The concerns generated by this phenomenon are however global, and as such, the inclusion of inequality in the analysis of the specific systems of innovation affords a degree of congruence between innovation studies and those of the global political economy. The basic assumption is that the nature of the specific systems of innovation, and their evolutionary paths, has a non-trivial effect on the manifestation of significant levels of inequality in its various dimensions. From this perspective, the five chapters that follow seek to understand the history of inequality and the manner in which inequality is being affected by economic policies in general and by industrial, trade and innovation strategies in particular. At the same time these chapters reflect on the effects of inequality, in their specific manifestations on the evolutionary paths of the respective national systems of innovation of the five economies.

Before proceeding further, it is important to define inequality. Broadly speaking, inequality may be seen to have at least two major aspects: opportunity and outcomes. The two facets are of course strongly related but are not identical. Opportunity refers to what we may call the ‘life chances’ of individuals and groups, whose determinants include a myriad factors deriving from economic, political and social contexts. Opportunity is difficult to measure except through proxy variables, including income, wealth, the various features of human capital, and access to the means for self-development.1 In this context, human capital can be seen as an enabler of personal life choice options. From this perspective we can avoid an economic reductionist assessment of inequality by contextualising measurements of human capital within a context of political and social constraints. Outcomes, on the other hand, are more easily measured, usually in terms of income, wealth and consumption patterns. While the two aspects of inequality are not identical, the endurance of a specific pattern of inequality of outcomes over time would tend to entrench corresponding patterns of inequality of opportunity. The concept of inequality is therefore considered in its multidimensional character, embracing a phenomenon that goes beyond the mere income dimension and is manifested through increasingly complex forms, including, among others, assets, access to basic services, infrastructure, and knowledge, as well as race, gender, ethnic and geographic dimensions. The different forms of inequality, whether class, gender, ethnicity, or geographic, have distinct implications on the effects of inequality and on the required counteracting policies. These forms often intersect, as with, for example, a correlation between race and class or the relationship between ethnicity and geographical setting, to create new configurations of the manifestation and the root causes of inequality. There are therefore two major features of the definition of inequality. The first is its expression in class, gender, ethnicity, and geographical forms, as discussed earlier. The second dimension to the definition concerns its manifestation in terms of income, wealth, education, health, etc., which determine both the quality of life and life opportunities. The focus on inequality in terms of opportunity and prospects highlights the structural nature of inequality which establishes it as an institution within the web which makes up the national system of innovation.

The types of inequality considered in this book, and the relative emphases placed on them, obviously differ across the five studies and are quite specific in terms of their underlying structures and histories. In the case of the two NSIs which emerged from centrally planned economies into new varieties of capitalism, the main focus of the respective studies is on class and geographical inequalities. This focus is most pronounced in the case of China, whereas in the Russian study, gender inequality is also included. The Russian study also identifies families with children as being particularly disadvantaged since the disintegration of the Soviet Union with the consequence of a recognised disincentive to have and raise children. In the case of India, inequality measures refer to religious groupings, as well as class and region. The Brazilian study also includes ethnicity, in terms of racial classification, alongside class and region. The history of South Africa obviously dictates that the conjuncture of race and class be considered in the assessment of the institution of inequality, along with geography and gender (Maharajh 2011). The choice of the types of inequality which have been considered in the respective country studies also carries implications for the complexity of the problematic posed by the proposed co-evolution of innovation and inequality. The wider the range of the types of inequality which are considered as relevant for a particular system, the greater is the potential for interrelations and causalities among the various types and sources of inequality. This tends to render both the phenomenon of inequality and the possibilities for its solution through policy more complex. The treatment of specific inequalities in these five studies is obviously not exhaustive, both in terms of inclusion and of emphasis. It represents, rather, a context-specific ranking of the types of inequality in terms of their relevance in the co-evolution between innovation and inequality.

The idea of co-evolution between innovation and inequality offered by Cozzens and Kaplinsky (2009) is a welcome contribution to the understanding of this complex relationship. They suggest that ‘innovation and inequality co-evolve, with innovation sometimes reflecting and reinforcing inequalities and sometimes undermining them’. The causal relations between innovation and inequality can also run in the opposite direction with high degrees of endemic inequality shaping the evolution of national systems of innovation. Here we can find the source of mutual self-reinforcing mechanisms between innovation and inequality which over time entrench and deepen the structural inequality of incomes, wealth and, more crucially, the life chances of different sections of populations. This forms the basis for a path-dependent vicious circle of innovation deepening inequality which further determines an evolution of the system of innovation which adjusts for the economic constraints posed by acute inequality, primarily in terms of the type and spread of human capabilities and learning capacities. This path dependency, especially given long historical reinforcement, would almost inevitably require state intervention to break this vicious cycle.

Fundamentally, the basis for the co-evolution between innovation and inequality is the fact that the foundations of inequality form one of the informal institutions of national systems of innovation. The treatment of inequality, and its basis, as an institution is premised on the assumption that the inequalities which we consider exhibit a degree of persistence over time. It follows that inequality emerges from established practices and relationships which endure, are structural and are subject to analysis stemming from an established theoretical basis. In this sense both the sources of inequality and the specific type of inequality itself can be considered as informal institutions. From this perspective we can therefore proceed to explore the factors which tend to reproduce inequality and it is only on this basis that we can eventually derive corrective policy recommendations. The study of the sources and effects of inequality thus becomes an integral part of the analysis of systems of innovation. Several theoretical approaches can be brought into the investigation of inequality as one of the institutional components of a national system of innovation and, given the political economy basis of the study of systems of innovation, these approaches almost necessarily tend to be contentious. Thus class inequalities are obviously subject to Marxian analysis while racial and ethnic inequalities would merit approaches to identity politics and the analysis of ethnic conflict, with gender inequality requiring the application of gender economics. Regional inequalities would probably best be approached from a more traditional development economics basis. These various approaches must not be seen as compartmentalised since the various forms which inequality can take are often conflated in a singular, contextually specific, local manifestation. Thus, for example, a roughly theoretically integrated approach is required to analyse the effects of globalisation on the shape and changes in inequalities of various forms within the context of specific NSIs as well as the more commonly studied effects on the inequalities between NSIs. In this way a more complex assessment of the systemic effects of the modern manifestation of globalisation can be brought to bear on to an issue which has come to occupy a prominent place in the analysis of the development of the international political economy.

The potency of the institution of inequality in terms of its specific manifestation differs dramatically across systems and again this is one of the examples where specificity matters crucially. In the case of South Africa, for example, it is impossible to understand the NSI without an understanding of apartheid, a unique example of entrenched inequality arising from a system of legislated racial discrimination which affected almost all aspects of life (Scerri 2009; Maharajh 2011). The uniqueness of this case among the BRICS systems of innovation is that until relatively recently racial discrimination in South African was a formal institution. Inequality in India, on the other hand, rises from a political economic context which has, since independence, been democratic and has outlawed discrimination on the basis of caste, religion, ethnicity, or gender. The enduring inequality in India is a deeply rooted informal institution and it is perhaps this very informality which makes it so difficult to eradicate simply through legislation.

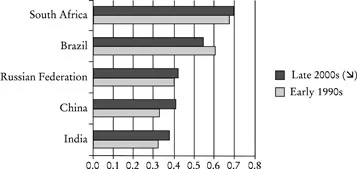

Inequality and poverty have historically defined Brazil’s and South Africa’s political economy and continue to constitute a worrying reality, notwithstanding recent improvements in the case of Brazil. The trend of increasing inequality in both China and India wherein the ‘Gini has overtaken the growth rates’ has attracted the attention of a number of scholars. Thus, as highlighted in this book, inequality is a peculiar trait of these countries comprising a key factor for understanding both the configuration and the dynamic of the national innovation systems of BRICS. Figure 1.1 shows the evolution of the Gini index from the early 1990s to the late 2000s in the BRICS countries.

We are of course fully aware that the referred trends are not confined to the BRICS economies. Inequality is shown to have increased in the global economy at an unprecedented rate over the last three decades, a period when knowledge intensity in the production process and international trade dramatically increased. This validation of the logic of the Prebisch-Singer theorem (see Singer 1950; Prebisch 1950) of the deteriorating terms of trade between developed and developing economies and the perverse effect of the neoclassical factor price equalisation theorem on the globalisation of class divisions should come as no surprise. On the one hand the increasing prominence of knowledge intensity as a determinant of international competitiveness tends to increase the inequality among NSIs. On the other, the accelerating rate with which knowledge and the access to knowledge has come to create competitive advantage at the interpersonal level has increasingly sharpened inequalities within NSIs. It seems, therefore, that NSIs can thrive even in the presence of large and enduring structural inequalities.

Figure 1.1: Change in Inequality Levels, Early 1990s versus Late 2000s* (Gini Coefficient of Household Income**)

This then is the conundrum which faces both the analyst and the politician. The drive to reduce inequality and eradicate poverty can obviously stem from a principled ethical stance entrenched in a variety of political agendas and ideologies. This however, is not always sufficient to bring about the necessary structural changes, especially in the face of the ubiquitous allure of the neoliberal ‘trickle down’ theory of the much vaunted welfare effects of free markets. It has to be clearly demonstrated that significant enduring inequalities within any NSI ultimately severely restrict its development and compromise its long-term viability. The immediately obvious argument for this proposition is premised on the deleterious effects of sustained inequalities on the development of broad-based human capital and human capabilities and the severe constraints which they impose on internal systems of consumption. The former effect imposes supply side restrictions on innovation, while the latter imposes constraints on the demand side of the innovation system. Beyond these effects there is also the other, more generic implication of sustained significant inequalities for the long-term political legitimacy, social stability and economic dynamicism of the polit...