![]()

Part I

An Overview

“You can resist an invading army; you cannot resist an idea whose time has come”. Victor Hugo’s notorious quote is what possibly best encapsulates the message carried by the first part of this book: the Circular Economy (CE) being the idea, the current production system – or take-make-waste linear model – being what needs to be replaced. This simple assumption is further elaborated in Chapters 1 and 2, with the former establishing the reasons why the human enterprise can no longer rely on its traditional economic paradigm, and the latter presenting the solid rationale behind what has been framed as an alternative system that “opens up ways to reconcile the outlook for growth and economic participation with that of environmental prudence and equity” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2014).

Arguably, the primary reason for the growing interest around the CE is its capacity to integrate environmental protection, social development, and economic prosperity all within a single, coherent, and actionable framework for sustainable development. Looking back, no other alternative approach has in fact ever acknowledged that economic growth does not necessarily require a corresponding increase in environmental pressure.

The time for a CE to blossom seems to have come. But why now? A number of diverse enabling factors, linked to regulatory, technological, and social trends, are facilitating its argumentation and acceptance. What remains to be seen are the ways in which private organizations (the engine of today’s globalized civilization) will strategically embed circular principles into their growth plans to future-fit operations and be ready to grasp new opportunities. The rest of this book lays out the authors’ view on the topic.

![]()

1 The Challenges of the Produce-Use-Dispose Model

1.1 Introduction

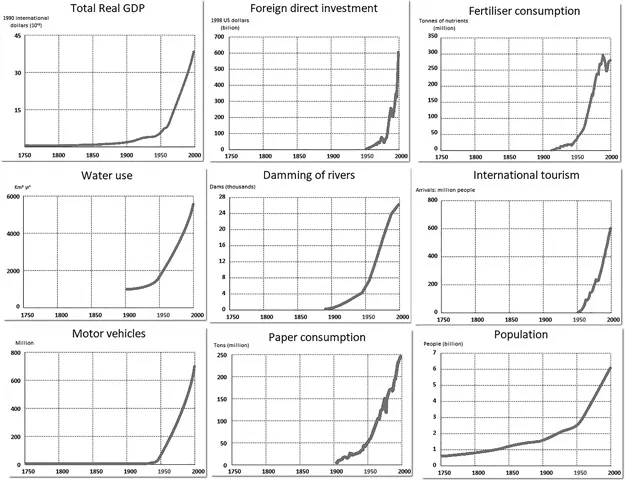

It has been estimated that between 1900 and 2000, global GDP has grown 20 times. Since the advent of the Second Industrial Revolution in 1880, and most notably after the end of Second World War, humanity has in fact experienced an unprecedented and steady growth in material wealth. Throughout the 20th century, the global economy has been radically re-shaped by the rapid industrialization of many regions of the world, boosted by the introduction of newer and more efficient production technologies, ever-lower labour costs, the creation of economies of scale, and the progressive globalization of markets. This extraordinary period of economic expansion has eventually culminated in a mass production of goods and services across all industries, delivering not only widespread material prosperity and higher-than-ever per capita disposable income, but also multiple tangible benefits in different key sectors of the human enterprise – e.g. better healthcare and longer lives, easy and reliable access to electricity, faster and safer transport, etc. The nine socio-economic trends reported later can be used to represent what the scientific community calls the “Great Acceleration”, i.e. the booming period that ran from 1950 until today (Figure 1.1).

What is now generally defined as “human development” has not come without a cost though. The industrial model standing at the roots of our current standards of living has been based around a linear system of production or take-make-waste paradigm, where natural resources are extracted from the Earth; then processed in manufacturing plants, where they become usable objects; items are then used; and finally get either incinerated or discarded as waste in landfills.

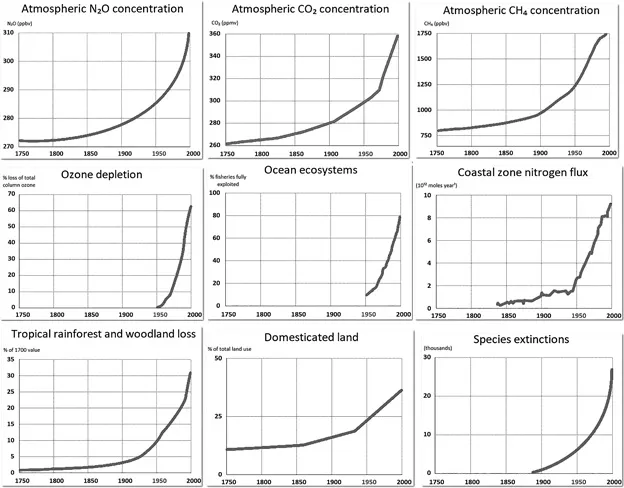

Each of these four steps causes a great deal of damage to natural ecosystems. Because of the amount of resources used on a worldwide scale and the industrial processes involved, ecosystems get heavily polluted (air and water), deprived of key substances (soil), or irreversibly modified (forests). Today, we extract and consume roughly 95% more raw materials than we did in 1880 and the numbers keep rising. The aggregate global material extraction rate of 35 billion tonnes recorded in 1980 nearly doubled in three decades to the current 65+ billion tonnes per year (Giljum et al. 2014). What is more, most assets end up being thrown away within just a few months from the time of purchase, resulting in waste generation levels exceeding 1.3 billion tonnes per year and projected to reach 2+ billion tonnes by 2025 (The World Bank 2012b). The situation becomes even more dramatic when considering that the linear economic model does not account for any effective regenerative actions.2 As a result, particularly after 1950, global economic activities have amplified the environmental footprint of the human enterprise, affecting the Earth system structure and functioning on multiple levels. The set of diagrams below illustrate some of the most notable damages caused, including deforestation and biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, and carbon dioxide emissions (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 The Great Acceleration.1

The positive correlation between human development and environmental degradation is evident. And although today we make more efficient use of natural resources – with 50% more economic value being extracted from a tonne of raw materials compared to just 30 years ago (OECD 2012) – a radical shift, away from the core pillars of modern development practices, is required to break the link between economic prosperity and the loss of natural ecosystems. Hence, whilst natural reserves could theoretically supply the linear model for a while longer and, in some instances, even see it scaled up to developing countries over the short term, proponents of an industrial system change are getting louder and evidence that the linear model has reached its tipping point is mounting. At least four trends are currently warning humanity of where it stands and of future dangers:

Figure 1.2 The Great Destruction.3

natural thresholds are being exceeded;

there is scarcity of raw materials;

the middle class with their demands is growing;

structural inefficiencies of the current economic model are worsening.

1.2 Exceeding Planetary Natural Thresholds

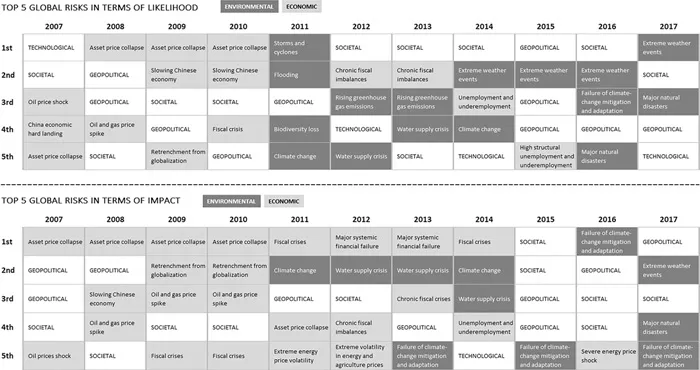

For the last 11 years, the World Economic Forum (WEF 2017) has been publishing a yearly “Global Risk Report” outlining the main dangers facing society and humanity. These risks are grouped into five broad categories (Economic, Environmental, Geopolitical, Societal, and Technological) and ranked according to their likelihood and impact. By looking at the top five risks identified each year since 2007, there is a clear trend moving away from economic threats (the clear majority over the period 2007–2010) towards environmentally related threats: “major natural disasters”, “failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation”, and “extreme weather events” above all others (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 The Evolution of Global Risks4

The shift in focus is firmly grounded in recent scientific discoveries (Rockström et al. 2009; Wijkman and Rockström 2012; Hughes et al. 2013; Steffen et al. 2015) alerting of the nexus between man-made activities and a progressive, irreversible change in the dynamics of the Earth system (i.e. the functioning of natural ecosystems typical of the last 11,000 years, throughout the Holocene geological epoch). Researchers have in fact collected evidence that our current path of development – with its intense use of chemicals, heavy reliance on fossil fuels, and ever-greater demand for virgin land – is on a collision course with the stability of the natural system. In 2009 and then in 2015, a team led by Johan Rockström at the Stockholm Resilience Centre was able to isolate and assess the state of nine key biophysical processes that regulate the stability of the Earth system and to delimit a safe operating space for humanity to keep our planet within its current hospitable conditions – i.e. mild average climate, abundant water and vegetation cover, and occasional natural disasters (Rockström et al. 2009; Steffen et al. 2015). Their study led them to publish the “Planetary Boundaries” (PB) framework, which received worldwide recognition as a coherent guide to global environmental sustainability management and development. The correct measurement of environmental sustainability is not always a straightforward exercise, but a substantial number of indices and indicators are already available and new ones continue to be defined (Cook et al. 2017). What follows is an account of the likely consequences that surpassing each PB will have on the business sector.

1.2.1 Boundary: Climate Change

Status: Safe limit surpassed and worsening. Today, the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide is already beyond the established safe limit (390 ppm CO2 against 350 ppm CO2), and keeps rising. Because of it, as per the latest (fifth) report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the global average temperature of combined land and ocean surface has already warmed by 0.85°C since pre-industrial levels (IPCC 2013).

Major impacts and industries most likely to be affected: As temperatures continue to rise, multiple extreme weather and climate events such as heat waves, heavy precipitation, droughts, cyclones, and high sea levels will inevitably be more frequent and marked by greater intensity. The primary ways in which these occurrences will have an impact on businesses are as follows:

More and tougher legislative regulatory regimes: Laws and regulations aimed at curbing greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions can affect firms on various levels, from imposing new taxes or costs, to limiting or banning specific activities or products (Tietenberg and Lewis 2015). Globally, climate change laws have seen a significant increase since 2009 (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2015b), with new cap-and-trade schemes becoming operational in China (since December 2017) and part of North America (since January 2018), and Sweden legally committing itself to become carbon-neutral by 2045. Carbon-intensive activities like oil and gas extraction; the production of iron, steel, aluminium, and paper; and civil aviation service are inexorably the main target of these new policies.

Impacts on physical manufacturing plants: Sectors like fashion, sportswear, toys, and automotive, all heavily relying on complex and elaborated supply chains, will predictably be the most exposed to business continuity uncertainty due to the growing risk of natural disasters hitting primary manufacturing hubs in countries like Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Bangladesh. As an example, the Thailand flood in 2011 caused Toyota a loss of 150,000 vehicles in output. Of course, it is not just manufacturing sites that will suffer. The risk extends to firms owning properties in climate-sensitive areas like coastal regions (e.g. hotel chains) or to those growing products that depend on favourable climate conditions (e.g. food producers). A case in point is the 2013 profit cut experienced by the world’s leading agricultural trader Cargill, whose operations had been severely hit by a massive drought affecting the U.S. that year5;

Damages to “intangi...