![]()

1 Commemorating the Present

Introductory Thoughts

Cuanto miren los ojos creado sea

Let all the eye sees be created.

Vincente Huidobro, Arte Poética

Photography does not belong to history as one

of its already-surpassed moments. In fact it is

photography (and increasingly so) that

becomes ones of those ‘productive forces’ that

drive both the production of history and its

reproduction, here ‘imaged’.

Francois Laruelle, The Concept of Non-Photography

… forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

Elizabeth Bishop, At the Fishouses

… Substitution

of the immutable

for the shifting, the evolving.

Louise Glück, “Nostos”, excerpt from Meadowlands by Louise Glück ©1996. Reprinted by Courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers and Carcanet Press Ltd.

… does what we have available to us now

deserve the name of photography?

Jacques Derrida

le réel, éternal vainqueur aux points [reality always wins on points].

Gilles Ortlieb, from Stephen Romer (Ed.) Into the Deep Street ©2009. Reprinted by courtesy of Carcanet Press Ltd.

The core proposition of this study understands that photography, considered either as a unified or dispersed set of related practices, remains one of the most effective and instrumental representational forms constituting contemporary culture. It maintains that photography continues to shape both the exteriority and the interiority of social existence taking its place as part of the evolving modernity characterised by Jean-Luc Nancy as “the epoch of representation” and present in the formation of the contemporary human subject described by Hubertus V Amelunxen as “homo photographicus” (Nancy 1993: 1; Amelunxen 1996b: 117; see also Richter 2010: xxviii). It argues that photography’s claim to having a distinctive referential effectivity can still be defended. But it is a proposition aware that, since even before the digital revolution, it rests on shifting foundations and is haunted by the possibility it might resemble Wile E Coyote having run off a cliff keeps on going over empty space for while until, hit by the realisation there is no ground beneath his paws and plummets to earth far below. Of art in general Terry Smith posed the question can it still “constitute the stuff of existence?” (Smith 2001: 8). Applying the question to photography, my answer is a “yes”—but a yes with complications.

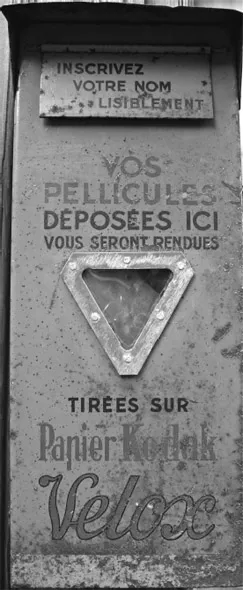

Figure 1.1 Vos Pellicules Déposées ici. Dieppe, 2015.

Photography is obvious. It is obvious in the original senses of the word meaning “being in the way” or something “frequently encountered”. It is obvious because it is ubiquitous and constant. From smart phone cameras stage—managing and networking our performances, through the medium’s numberless pragmatic, forensic, ideological, promotional, hobbyist and aesthetic applications, to surveillance cameras observing from wall or sky monitoring our presences, owning our public spaces, photography remains an unavoidable facilitator and mediator of knowledge, identity, pleasure, social relations and of the arrangements of power. The medium has shown an evolutionary ability to adapt and absorb other forms. As Sontag observed, it is phagic, it devours other forms of visual culture. It is the Dr Who of visual media. It appears then that photography, at least photographic effects, remain inherent within our lives and worlds, constituting a kind of immanence.

Photography still articulates the contemporary because certain of its own characteristics mirror those of contemporary modernity itself. In other words, photography remains constitutive of the cultural spaces we inhabit being in a way, a creature of them. An example is modern culture’s obsession with the present on one hand and its constant flight from it on the other. It is a contradiction which finds an equivalence in the ceaseless modulation of presence and absence at the heart of photographic representation—whose imagery is both indexical and spectral. Similarly, the double nature of the photograph as both a capturing or fixing of a fleeting reality and as an all too fragile or erasable material artifact echoes how modernity is at once defined by its own productions and systems and yet haunted by their destruction, pulled down by the same forces that brought them into being. As often it was Baudelaire who understood the deeply contradictory and conflicted nature of a then emerging modernity. He writes: “De la vaporization et de la centralization du Moi. Tout est là” (Baudelaire 1961: 1271)/“Of the vapourization and centralization of the Ego. Everything depends on that” (Baudelaire 1969: 49).

Societies institute themselves, writes Cornelius Castoriadis, by “instituting a world of significations” (Castoriadis 1987: 360). Charles Taylor, in a similar vein, utilises the term “social imaginary”, which he defines as:

the ways in which (people) imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations.

(Taylor 2004: 23)

Taylor underlines his use of the term ‘imaginary’ as his focus is “on the way ordinary people “imagine” their social surroundings”. More often than being expressed theoretically, he notes, they are “carried in images, stories and legends” (Taylor 2004: 23).

Photography is one of many processes through which the social imaginary is represented, confirmed and distributed. It is a crucial medium in the “culture of generalised communication” or “mediatized culture” (Vattimo 1992; Hepp 2013). Its emphatic if only apparent realism, that is, its ostensibly non-linguistic essence, becomes a form of enforcement or naturalisation of the values of the social imaginary, as though putting them beyond discussion. No debate over photography’s social functions or its claims to evidential authenticity can exclude a discussion of how it is implicated in the politics of presence where visibility is linked to power, establishing what Gary Shapiro has called, a visual régime. With acknowledged echoes of Foucault Shapiro identifies a major characteristic of a visual régime as lying in

what it allows to be seen, by whom, and under what circumstances. But it is also a question of a more general structuring of the visible: not just display or prohibition, but what goes without saying, not what is seen but the arrangement that renders certain ways of seeing obvious while it excludes others.

(Shapiro 2003: 2–3)

As we shall see in a later chapter, the restriction of visibility has been utilised as a weapon of political repression.

A visual régime organises what Jacques Rancière calls the “distribution of the sensible”. The concept widens the meaning of the term “aesthetics” to describe how “ forms of visibility” are arranged in a more generalised social space than those of exclusively art practices. They are, he writes, a system

of a priori forms determining what presents itself to sense experience. It is delimitation of spaces and times, of the visible and the invisible, of speech and noise, that simultaneously determines the place and the stakes of politics as a form of experience.

(Rancière 2004: 13)

What he calls “primary aesthetics”, are not the exclusive domain of art. They are forms actively present in shaping how experience and understanding are articulated and presented across the whole of social life. Art practices are aesthetic interventions into social and cultural practices already formed by “primary aesthetics”. They are, writes Rancière,

“ways of doing and making” that intervene in the general distribution of ways of doing and making as well as in the relationships they maintain to modes of being and forms of visibility.

(Rancière 2004: 13)

A work titled Where We Come From (If I Could Do Something for You in Palestine What Would It Be?) 2001–2003 by the Palestinian artist Emily Jacir contests a certain visual régime, or rather it side-steps through what is as much an act of kindness as it the production of an aesthetic statement. In possession of a United States passport and therefore able to visit Israel Jacir asked Palestinians prevented from doing so by the Israeli authorities, what she might do for them while in Israel/Palestine. One asked her to visit his Mother’s grave. The image shows the gravestone with Jacir’s shadow passing over it, a mark of her presence, her gift of the presence disallowed the son, her presence standing in for his.

My aim in subsequent chapters is to illustrate how photographic practices have been engaged in the formation but also in the investigation or contestation of the visual orders theorised by Shapiro and Rancière among others. Their engagements are not always radically antithetical, not necessarily desiring the thorough disruption of dominant visual régimes. Some do. For the most part, while they are critical in all senses of the imposed languages of representation, their aim is to complicate or, rather to, recomplicate how we see and how it conditions what we see and the meanings we can draw from it. Much of contemporary photography now represents a resolute uncertainty about the veracity of its statements. Yet, as the conveyor of provisional truths it represents a powerful opponent of certainties which so often charge the armories of oppressive power structures and their rigid imaginaries.

Photography, then, can be a means of imposing a visual régime. It is more than that, being itself what Castoriadis calls a materialisation of “imaginary significations” central to the contemporary order (Castoriadis 1987: 361). The medium embodies certain of the necessary myths of modernity such as the link between science and technology, the link between its realist claims and positivism. It exemplifies the synthesis of culture and technology and the production of symbolic goods. Through mass ownership of cameras it is associated with the idea of mass cultural democracy. It is mass produced, immediate and globalised. It progresses: able to re-invent itself as modern, and at each change to transform what is meant by the term photographic. Finally, on behalf of the modern, photography has heroically usurped the powerful spell of traditional society’s mythical or sacred time. Traditionally, sacred time, described by Mircea Eliade as a “succession of eternities”, might be made present through ritual (Eliade 1987: 88). In the ritual of the photographic image the passing moment becomes an unchanging eternity—an “eternal present” the sacralisation of the everyday (Eliade 1987: 88).

Photography states the obvious. Yet in doing so it can destroy its obviousness: outstare it; reveal the strangeness of things and the complexities of seeing; look into the overlooked; unsettle the self-evident; introduce the precise uncertainty of the poetic, thereby proclaiming what Geoff Dyer calls the “the poetry of comprehensive contingency” (Dyer 2005: 4). Much of photography is a simple celebration of what exists, an activity that places it at the heart of an evolving modern condition described by the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz. Miłosz traces a passage from a religious to a post-religious culture in terms of the shift from a view of the world as filled with symbols and allegories to one made of things as themselves devoid of resident gods. He writes,

Untranslatable into words, I chose my home in what is now In things of this world, which exist and for that reason delight us.

(Milosz, 1993)

However, as we shall see, the visual expressions of secular modernity have not remained unchallenged; the metaphysics of the image have not departed.

Photography in this moment is also elusive: easy to find, but hard to recognise—and definable in multiple ways. While it remains, in John Tomlinson’s words, “one of the great emblematic artefacts of modernity”, digitalisation, speeds of image transmission, global mass usage and changes in economic and social formations accompanied by the rise of more sceptical takes on representation, have together transformed the ways in which photography is understood (Tomlinson 2007: 72). For much of the last 30 years, as the digital epoch advanced, the very idea of a single distinctive entity called photography has become seriously questioned. Numerous jeremiads have prophesied its effective demise. These assertions and anxieties are now, like the medium itself, also obvious. Nevertheless they need some re-describing.

In his essay “Ectoplasm”, a piece written mostly in the 1990s, Geoffrey Batchen itemises a number of important descriptions of photography’s uncertain condition following the advent of digital technologies. The status of the photographic document itself was challenged (Tim Druckery). Its claim to truthfulness was being undermined (Fred Ritchin). Its very medium specificity may have disappeared (Anne-Marie Willis); and if it was not already a corpse, then photography was certainly “radically and permanently displaced” (William J. Mitchell in Batchen 2005: 129). These descriptions are echoed elsewhere. Terry Smith wonders if given the excess of images in the world photography has become enervated (Smith 2001: 1–7). John Roberts links the loss of reliance on photography’s indexical power since digitalisation with a detachment of the medium from its role in political criticism and resistance which had been based in the revelation of social reality utilised to contest dominant ideologies, naturalised myths and official versions (Roberts in Kelsey and Stimson 2008: 164; see also Paul Willemen and Dai Vaughan in Doane in Kelsey and Stimson 2008: 5). George Baker notes how, as the borderlines between photography and other media and art forms have become unstable or reinvented, the practice is at risk of becoming lost in its own “expanded field”. “Even among those artists,” Baker writes, “who continue in some form the practice of photography, today the medium seems a lamentable expedient, an insufficient bridge to other more compelling forms” (Baker 2008 in Beckman and Ma 2008: 177). James Elkins wonders if photography now survives only through being hooked up to a conceptual life support system being, he writes, “intravenously fed by pure streams of academic art theory” (Elkins 2011: 110). Touché.

And yet what seems to have happened is not the effective disappearance of photography through the dispersal of its aspects and elements. In many respects it displays a more vigorous cultural existence than ever before, a condition brought about by two quite different reactions sharing the conviction or hope that photography remains a d...