![]()

1 Geometric and botanic simulation

Until the early 1960s, the computer simulations used in morphogenesis problems had developed in an inchoate and divergent manner, based on issues that were essentially specific to professional mathematicians. It is important, therefore, to first reconstruct the factors that enabled these simulations to evolve towards greater biological realism. The simulations I will consider are of three types: geometry and probability-based, logic-based and pluriformalized. We will see how their implementation broke not only with the traditional uses of the computer as a calculator of models, but also with the pragmatic epistemologies of these models. These simulations, which were successfully adopted by biologists, were the first to establish closer links with work in the field, but they would not be the last. This series of initial intersections with the empirical opened the way to an era of convergences with many different dimensions. In this chapter, in particular, I will show that certain biologists (such as Dan Cohen and Jack B. Fisher) were ultimately able to make good use of simulation once they managed to accentuate its ability to produce a representation on a geometrical level – albeit at the cost of reducing their ability to take the temporal heterogeneity of plant-growth rules into consideration.

The probabilistic simulation of branching biological shapes: Cohen (1966)

We find the first use in biology of a particular type of discretized computer simulation in the work of the Israeli biologist Dan Cohen (born 1930). What interested Cohen (at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) above all was the possibility of forming a theoretical argument on the processes of morphogenesis. His aim was to improve on the work of his MIT colleague Murray Eden (born 1920), by trying to find certain concepts that were specific to the botanical morphology and embryology of the time, including those of Conrad Hal Waddington (1905–1975), an embryologist and organicist. Eden, an engineer and mathematician, had worked with the linguist Morris Halle (born 1923) in 1959 on a letter-by-letter modelling of cursive writing, using a succession of elementary probabilistic choices with multiple branches. He demonstrated that a numerical simulation of this combinatorial analysis to biological morphology situation, when depicted on a plane (random branching on a grid of square cells), could, in a first approximation, be considered analogous to cellular multiplication.

In 1966 Cohen recognized the value of this spatial representation of intertwined calculations. He set out to theoretically test Waddington’s hypothesis of a morphogenesis conceived as the result of a “hierarchically ordered set of interactions between genes, gene products and the external environment”.1 Cohen adopted the concept of “epigenetic landscape” that had been introduced by Waddington in 1957 in The Strategy of the Genes, in which he adapted to an ontogenetic scale the earlier (1932) notion of “adaptive landscape” proposed by the American geneticist Sewall Wright (1889–1988). Cohen’s aim was to thereby link his own evolutionary ecology questions to this morphogenetic problem of epigenesis. Without wishing to precisely calibrate his morphogenesis model on actual cases, he nonetheless wished to demonstrate a general overall feasibility: the feasibility for living beings of undergoing progressive and adaptive growth and development without requiring reference to excessively complex laws, with such complexity being expressed in terms of “information”. According to Cohen, if one could write a “minimal” program using the “simplest possible”2 rules of generation for branching shapes that were already relatively realistic from a global and qualitative point of view (as judged by eye), then one could consider that the plausibility of Waddington’s epigenetic hypothesis had been increased, along with the analogous hypotheses of evolutionary ecology.

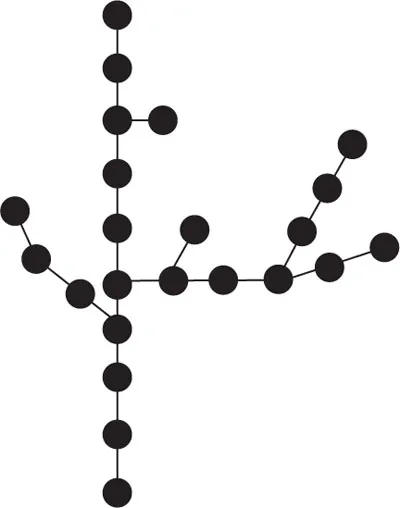

To this end, a branching structure was drawn by a computer connected to a plotter. Cohen then followed Eden’s probabilistic approach for branching. But in order to clearly demonstrate the usefulness – from the point of view of theoretical biology – of what Eden called the apparition of “dissymmetry” in cellular multiplication, Cohen planned to take into account the morphogenetic “density field”, as it is known in embryology. This is the key to simulation’s shift from combinatorial analysis to biological morphology. This concept of “field” had already been introduced in embryology in 1932 by Julian S. Huxley (1887–1975). In basing his own model on the physical concept of field, Huxley had hoped to generalize the notion of gradient (1915), which had originated with Charles Manning Child (1869–1954), by removing the bias toward a specific axial direction. This notion was then taken up by Waddington in order to explain the embryological phenomena related to this principle – which had been established in botany since 1868 – of growth towards the greatest available free space (Hofmeister’s principle). If Cohen was to take this field into consideration using Eden’s simulation technique, however, he could not make do with just a grid of square cells. He therefore came up with a geometric plane with a much more detailed spatial resolution that included the 36 points adjacent to the initial point of growth or of eventual branching, with each point separated by a 10° angle (since 36 × 10° = 360°). Each of these 36 directional points was affected by a “density field” calculated on the basis of the distances from each point to the other elements of the tree being constructed. Following Eden’s extensive discretization, Cohen was thus obliged to make the space of biological morphogenesis geometric once again, since he could not otherwise see how a sufficiently realistic plant form could be designed if he retained such an over-generalized cellular approach. Instead, he reduced the mesh size of the grid, and above all retained the probabilistic formalization.

The length and angle of growth that took place from the starting point were determined by the density field. The branching rules were also affected by this density field, but were above all probabilistic. A test was carried out at each growth point by random number selection (pseudorandom), in order to determine whether or not the computer should add a branch in that direction. Finally – and it was here that Cohen could introduce his idea of a programmed epigenesis that was nonetheless sensitive to environmental events – he reused Eden’s concept of variable branching based on the directions of the plane: this made it possible to simulate heterogeneous density fields arising either from the presence of other parts of the organism or from the potential pre-existence of a physical obstacle outside the organism. Using this programming flexibility, Cohen could also simulate areas that, on the contrary, facilitated growth. For Cohen, the resulting shape was conclusive, since it brought to mind experiments in mould growth on a heterogeneous nutrient substrate.

Cohen also chose to vary the growth and branching probabilities in accordance with the order of the branch in relation to the trunk. A branch attached to the trunk was order 1; a branch issuing from this branch was order 2, and so on. In this way, the hypothesis of hierarchically organized genesis could be tested, since the order represented a difference in biological status on the level of the general organization of growth. Since the diagrams that were generated by the plotters appeared to Cohen to resemble qualitatively realistic trees, leaf veins or even moulds, he considered that the results of the simulation were very conclusive. It had been able to rise to the two initial challenges of his theoretical epigenesis problem: 1) to prove the credibility of biological growth that is constrained by rules that have a fixed form, but whose parameters are at the same time sensitive to environment; and 2) to prove the credibility of the theoretical representation of this growth process as being hierarchically organized. This entire simulation process was published in the Nature journal in October 1967.

The epistemic functions of modular programming, simulation and visualization

As a result of the conditional branching made possible by computer programming, the model was able to incorporate a sensitivity to environment expressed as a feedback effect from the environment on the genetic parameters. These sub-routines had the property of seeking the spatial optimum by self-adapting the rules of growth. Cohen then noted that these mathematical rules, which were constant but nonetheless had variable parameters, were extremely simple. The brevity of his FORTRAN program (only about 6 ∙ 104 bits) merely confirms the feasibility of this type of scenario in nature: the small size of the program substantiates the initially counterintuitive idea that natural morphogenesis requires only a limited amount of elementary “information”. Cohen even assessed the number of genes that would be necessary for the biological insertion of these 6 ∙ 104 bits, and calculated that it would amount to 30 genes.4 The briefness of the informational message was due to the modular nature of the programming, which avoided the repetition of computer instructions of the same type. Finally, it should be noted that, with this model, Cohen used the ability of MIT’s computer at that time – the TX-2 – to visualize these calculations of point positions on a plotter so as to evaluate his project’s success: he hoped to demonstrate visually that a hypothesis of growth that was both structured and epigenetic could apply to natural phenomena. For Cohen, as we can see, simulation by digital computer served essentially as a means of testing theoretical hypotheses. Similar ideas had already been expressed since the earliest days of digital computers, initially in work on nuclear physics, and later in biochemistry and physiology.

According to Cohen, two specific conditions had to come together in order to consider that a simulation could enable a biological theory to be rejected. In the first condition, the computer program itself must “incorporate” the hypotheses. To begin with, it materialized or embodied, so to speak, something that until that point had been merely spoken words. In this sense, it became closer to the empirical. Furthermore, the prevailing view of the times, which represented the genes as information units and the genome as simply a program, assisted in this identification. Next, the use of the plural term “hypotheses” must be noted: the program fleshed out a set of hypotheses and not just one isolated hypothesis. As we have seen, there was a variety of rules that replaced the uniqueness of one law. In this program, there were growth rules and branching rules: these two types of presumed rules were tested together, overlapping each other. For the second condition, it was necessary that a comparison could be made with natural shapes. In other words, the simulation could not have the power to discard hypotheses unless the computer could provide a means of comparison with the empirical: the simulation did not, of its own accord, reject a set of hypotheses; its ability to reject had to come, by transitivity, from the strong resemblance of its results to what is seen in nature. Thanks to the technical visualization system added to the TX-2 computer, however, the simulation could transmit its ability to discard morphogenetic theories to the computer – an ability that, until that point, had been the prerogative of actual or physically simulated experimentation.

It should be noted, nonetheless, that this comparison (and therefore this relationship of transitivity) was carried out here in a purely qualitative manner, or “by eye” we might say. It is no doubt for this reason that, unlike Eden, Cohen – who was well informed in the subject of biological substrates – was the first to use the term “simulation” to refer to this type of modelling and visualization of living forms by computer. Indeed, the title of his 1967 article is “Computer simulation of biological pattern generation processes”. He owed his use of the term in this context to his acquaintanceship with the cybernetician von Foerster.5 But according to Cohen, the occasionally qualitative nature of the comparison in no way diminished the unambiguous nature of the overall process of hypothesis testing, because he was alluding only to phenomena of shape that had already been identified as being typical, generic and easily recognizable globally and to the naked eye. In the case of a theoretical approach, the diagrams produced by the plotter evoked clearly enough – for those specialized in the field – real organisms that have been observed in real life. The diagrams thus did not prove the hypotheses, but nor did they reject them, and above all they might retain the hypotheses as being plausible despite having seemed scarcely likely beforehand.

At first, due to the inadequacy of the classic mathematical languages, the biology of shapes was unable to directly include the shape of living organisms in a single formal language so as to then attempt to reconstruct their evolution by means of an abstract model. For this reason, as we see in Cohen’s work, the biology of shapes came up instead with local hypotheses – which for their part could be formalized by computer – about what generated these shapes, in order to make them construct what we see on an integrated scale: the overall shape. It was these atomi...