![]()

Part I

The use and supply of doping products

![]()

Chapter 1

Assessing and explaining the doping prevalence in cycling

Werner Pitsch

In recent years, a line of empirical studies succeeded in validly estimating the doping prevalence in elite sport as a whole and specifically in cycling. In each study, variations of the randomised response technique (RRT) were used, but they nevertheless ended up with more or less comparable results. Empirical social research thus provides a reliable description of the extent of doping in different contexts, while the development of theories explaining doping lacks the quality to provide coherent explanations of quantitative phenomena. This discrepancy was mentioned by Pitsch and Emrich (2012), but despite this desideratum, theoretical reasoning and empirical research did not succeed in closing this gap.

The following chapter will begin with a brief explanation of indirect questioning techniques to enable the reader to assess both the reliability and limitations of results from these methods. After an overview of empirical results on doping prevalence in elite sport, and especially in elite and amateur cycling, theories of doping will be contrasted using research questions arising from these results. Based on an astonishingly consistent pattern of results across different settings, we will demonstrate how social scientific theory can be linked explicitly to empirical data. The potential of this methodology in terms of clarifying essential and abundant elements of the description of the empirical field, as well as pointing at research desiderata and to new hypotheses, will be highlighted in the end.

Indirect questioning techniques

Indirect questioning techniques allow respondents in surveys on embarrassing or threatening topics to answer honestly without compromising themselves. The randomised response technique was the first of these techniques, developed more than 50 years ago (Warner, 1965). Since then there have been many methodological studies investigating advantages and risks of different variants of this technique (for an overview, see the meta-analysis by Lensvelt-Mulders, Hox, van der Heijden, & Maas (2005) and the recent review by Wolter (2012)). The rationale of these techniques is to use some randomisation like flipping a coin or rolling a dice in the process of answering an embarrassing question. This randomisation is implemented in a way that is clearly understood by the respondent. Thus, respondents understand that an embarrassing answer can be the result of the randomising process or of answering the embarrassing question truthfully. There is much evidence that indirect questioning techniques effectively reduce the social desirability bias for sensitive issues (Lensvelt-Mulders et al., 2005). As the researcher knows the characteristics of the randomising device, he or she can calculate the proportion of honest yes- and no-answers to the embarrassing question, while the respondent recognises that there is no way to infer his/her property or behaviour from his/her individual answer.

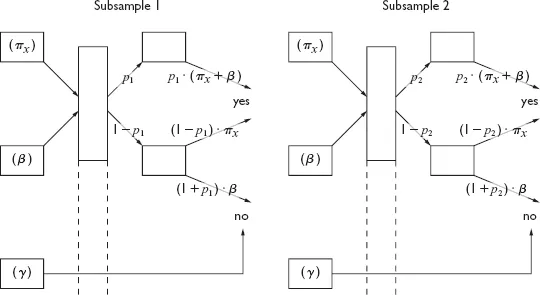

Although respondents are more prone to answer the sensitive questions honestly, there remains a bias due to either inappropriately handling the randomising device or to deliberately cheating when answering. In order to control for this effect, Clarke and Desharnais (1998) developed the first cheater-detection technique, typically used for no-cheating when the embarrassing answer is ‘yes’ (see Figure 1.1). Feth, Frenger, Pitsch, & Schmelzeisen (2017) expanded this technique to a total cheater detection, which can be used to detect no- as well as yes-cheaters.

RRT has been used for doping in sport repeatedly on different populations by performance (elite athletes: Elbe & Pitsch 2018; de Hon, Kuipers, & van Bottenburg, 2015; Pitsch & Emrich, 2012; Pitsch, Emrich, & Klein, 2007; amateur athletes: Frenger, Pitsch, & Emrich, 2016) and from different disciplines (track- and-field athletes: Ulrich et al., 2017; triathletes: Dietz et al., 2013; Schröter et al., 2016). In particular, concerning doping in cycling, there have been studies on elite Flemish cyclists (Fincoeur, Frenger, & Pitsch, 2014; Fincoeur & Pitsch, 2017) as well as among amateur cyclists licenced by USACycling (see below). For this chapter, the results from two studies among cyclists are considered. A population of Flemish cyclists was studied in May and July 2013 (Fincoeur, Frenger, & Pitsch, 2014). Among other questions, there was an RRT question on doping during the last season:

Have you used forbidden substances or methods in order to enhance your cycling performance during the last season? (TUE excluded)

Figure 1.1 RRT with no-cheater detection.

An invitation to participate in this study was sent to 2776 Flemish cyclists by e-mail. After three reminders, there were 767 responses. Due to the cheater-detection method used, one cannot calculate for a point estimate of the rate of dopers in a population. Rather, an interval indicating the span between the rate of honest yes-responders – which equals the lowest possible level of dopers in the population – and the rate of honest yes responders plus the rate of cheaters, which reflects the upper limit of the interval. In contrast to the suspicion that cycling is a debauched sport with professional cyclists all being doping sinners, the results for the prevalence estimates for this study indicated the overwhelming majority of respondents is likely a non-doper. The rate of honest yes-responders for last season doping was estimated at 0.4%, with 26.3% cheaters and 73.3% honest no-responses. The important issue when interpreting these results is that the rate of honest no-responses is surely an unbiased estimation of the no-doping prevalence, as the rate of no-cheaters (presumably due to social desirability) is explicitly estimated with this technique. Besides this, the rate of honest yes-responders is also very likely to be a valid lowest threshold estimate, as the probability that this rate is inflated by yes-cheaters can, especially among elite athletes, be plausibly assumed to be extremely low. Accordingly, both the rate of honest yes- and of honest no-responses are the lowest assumable figures for dopers and non-dopers in the population.

The same questions were used in a survey among amateur cyclists who were licenced by USACycling in 2014. As USACycling did not share their list of contact data with the researchers, the communication with the respondents could not perfectly be controlled. Concerning the response rate, this was not seen a priori as a massive disadvantage as the large population count (51,782 licence holders in 2014) left enough room to end up with a sufficiently large record set even at low response rates. A total of 39,000 members of USACycling who had opted for e-mail communication were invited via a newsletter to participate in the survey. The reminder was sent to 44,133 members of USACycling. The discrepancy in the number of addressees between the two communications remained unclear to the researchers. The survey started on 04 September 2014 and was finished on 27 October 2014.

The response added up to 3756 records from respondents who had at least started to answer the questionnaire and 2949 complete records. Due to question- and/or item non-response, this figure is higher than the number of exploitable results for single items and especially higher for calculations referring to more than one item (e.g. estimating the doping prevalence by licence level).

Although USACycling provided in-depth information on the distribution of the population by age, discipline, sex, and performance class, the return could not be tested for being representative. The ‘doping’ focus of the study made only cyclists who actively participated in competitions relevant for the research. This was attained by a question in the beginning of the questionnaire asking if the respondent participated at least in one competition during the last two years. Respondents answering ‘no’ were immediately directed to a webpage thanking them for their interest in the research and explaining that they did not belong to the relevant subpopulation. The main objective of this technique was to avoid an artificial underestimation of doping prevalence as a result of cyclists with other motivations than being successful in competitions (e.g. saving money for accident insurance) entering the sample. As a side effect of targeting this subpopulation, the researchers were unable to test if the sample represents the subpopulation of actively competing amateur cyclists, as this subpopulation is not recorded by USACycling.

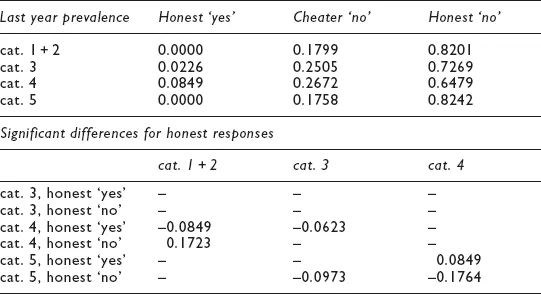

Analysis resulted in a best estimate of 3.15% for the prevalence of last year doping, which did not differ significantly from zero. The estimated rate of honest ‘no’-responders is 74.88%. The true score of the last year prevalence thus ranges between at least 3.15% and 25.12%. Compared to other studies in amateur sport (Frenger, Pitsch, & Emrich, 2016), this rate is not astonishing and there is no hint that doping in amateur cycling was more prevalent than in any amateur sport in general. What was especially interesting is the pattern of doping prevalence when differentiating by performance category. To conduct these analyses, cyclists were grouped according to their USACycling amateur performance category. These categories range from 1 (topmost performers) to 5 (lowest performance category). Due to the low number of records among category 1 cyclists, we grouped categories 1 and 2 together and conducted no-cheater detection analyses. The reasons for omitting the yes-cheater detection are as follows: (1) the overall estimate of this proportion yielded a value of 0 (see above) and (2) the no-cheater detection already provides stable results for sample sizes that are too low to perform a total cheater detection (Feth et al., 2017). The results for the last year prevalence (Table 1.1) strongly support the findings from elite sport, discussed above. As can be seen in the following table, the rate of honest ‘yes’-responders was calculated to be zero for categories 1 and 2 as well as for category 5, while the estimates for categories 3 and 4 were above this level. The significant differences support the pattern showing doping is less prevalent at the highest levels of competition. Additionally, doping is less prevalent where performance and success are the least important (category 5).

Similar results were repeatedly reported in elite sport, as internationally competitive athletes showed a lower doping prevalence than the category of nationally competitive ones (Pitsch & Emrich, 2012; Pitsch, Emrich, & Klein, 2007). As a result of this research, we find nearly equal overall levels of doping prevalence among elite and amateur cyclists, while the pattern of reduced doping prevalence among the top performers compared to athletes at lower performance levels persists at both levels.

Table 1.1 Comparison of doping prevalence at different licence categories

Initial ad hoc explanations (Pitsch, Emrich, & Klein, 2007) for this prevalence pattern in elite sports were built on the assumption of athletes rationally making doping decisions based on balanced utilities from doped and non-doped sports, and the probabilities of success, detection, and sanctioning. With this rationale, the lower prevalence among the top performers was thought to originate from the higher risk of detection as well as the higher loss in utility after being detected and sanctioned. Therefore, present anti-doping policies that concentrate doping tests at higher levels of performance were thought to reduce the amount of doping at these levels, but also to increase doping prevalence at lower levels of competition. Nevertheless, this rationale does not hold for amateur sport as (1) there are no massive gains to win from being successful in competition and (2) doping tests are scarce at every level and therefore the probability of detection at the top level nearly equals the probability at lower levels.

The aim of the following considerations is to find a coherent explanation that works on both levels of performance. To end up with different explanations for similar patterns in elite and in amateur sport would also require explanation of how these areas differ qualitatively and how this difference yields similar results when it comes to decisions for deviant behaviour. In this context, the difference between amateur sport and professional sport is only a qualitative one from the perspective of sport organisations. Differences at the athlete level are mostly quantitative in terms of performance, but also in terms of loss such as time spent on training, money spent on equipment and travel, as well as in terms of utility like prize money and public attention. At least between high-level amateur sport and low-level professional sport, this is a very blurred line.

The explanation developed in the following chapter also accounts for results from studies on the relationship between the level of prize money and the doping prevalence in different sports. Frenger, Pitsch, & Emrich (2012) had studied the relationship between prize money and prize money gradation in Olympic disciplines and the estimated doping risk in these disciplines. The doping risk was estimated by experts, forming the group of independent observers at the 24th Olympic Games in Beijing (WADA, 2009). The results showed that the level of the mean prize money in different sport disciplines was positively correlated with the estimated doping risk. However, within each discipline there was no correlation between the possible relative gain by performing higher and the doping risk estimate. Therefore, economic incentive-theories (like e.g. used by Maennig, 2002) may well explain different levels of doping between sports but cannot explain doping decisions of athletes at different levels of performance within one sport.

Problems of theory development in the doping field

Social scientific theories used to explain doping so far cover both domains of sport but ignore empirical evidence showing different doping prevalence in different disciplines and at different levels of competition (e.g. psychological explanations, building on moral (dis-) engagement, Melzer, Elbe, & Brand, 2010, ...