Introduction

It is traditionally taught by accounting historians (Melis, 1950, 19–20) that the rise of modern accounting history coincides with the first printed work we know—that is, the Summa by Luca Pacioli.

Yet double entry had already been invented and had been in use for over a century in the small business houses of Italian merchants. Its conception tided up with the flourishing of trade thanks to the development until the end of the fifteenth century of independent communes, signorias, princedoms and maritime republics and to the connected need to control and report acts of management of companies, which had grown in both dimension and business scope (Peragallo, 1938, 1–37; De Roover, 1955, 405–420).

It’s hard to know who the first author to write a work about double-entry bookkeeping was, since until the last decades of the fifteenth century Gutenberg printing didn’t exist (invented in 1455 and slightly introduced in Italy starting from 1463).

Consequently whoever wrote about the subject before that time couldn’t issue his work, which remained as a manuscript, with the exception of Benedetto Cotrugli’s (cf. § 3.1), which was rediscovered and printed 115 years after its writing.

Otherwise, already before the publishing of the Summa by Pacioli in several towns of the Italian Peninsula there were master charts of accounts bookkeeping and masters who taught double entry (Bariola, 1897, 59–63; Besta, 1916, 345–346; Melis, 1950, 59).

Thus it is probable that those very preceptors, at least some of them, had arranged somewhat structured notes to carry out their work. A well-known example is Master Troilo, quoted in a 1457 ledger and journal belonging to Nicolò and Alvise Barbarigo’s brothers. In them the “quattro soldi lira di grossi” (four coins of heavy lira) expense is entered to pay “maistro” (master) Troilo as a compensation for teaching bookkeeping in the previous six months (Alfieri, 1891, 108–109; Besta, 1916, 345–346, 376–377).

In that period many others taught the double-entry method to merchants and, generally, they were the same teachers of abacus and calligraphy, which were never carried out separately according to the custom of that time.

Actually, by chance, even some of the first printed books—which were issued in low quantity due to the high cost of printing, above all in the early years—could have been lost. Vittorio Alfieri reminds us (Alfieri, 1891, 109) that in a journal dated 1484 entitled “Zornale R” owned by Francesco Minuzani, a Paduan librarian who worked in Venice, there is a list of books of his small business house where works of bookkeeping and abacus are referenced, some of which have not been catalogued in any library.

It is possible that these works contained references to double entry, due to the strict relation of the aforementioned subjects.

According to the updated knowledge, the first author in the timeline who illustrated the double-entry method was Benedetto Cotrugli in a manuscript dated 1458. There is a wider edition too, which has been found only in the 1990s and is known as “Malta’s manuscript” (Sangster, 2014). This is also the only celebrated manuscript enshrining double-entry notions which was arranged before the Summa by Luca Pacioli.

It is worth noting that the first Italian double-entry treatises were all issued in Venice—from Pacioli up to the early years of the seventeenth century, and thus for over a century—except for a chapter of the 1539 book by Gerolamo Cardano (Cardano, 1539) and the 1586 edition by Angelo Pietra (Pietra, 1586). This witnesses the pivotal and privileged role in cultural hegemony played by Venice for such a long period of time. Starting from the seventeenth century the publication of accounting works spread all over the territory.

The principal aim of this work is to frame the Venetian treatises compared with double-entry works in the Italian Peninsula. Following, the contents of the most relevant writings will be briefly commented on in order to find a “conceptual frame” of the contributions provided by several authors to the growth of accounting. Some of these books are widely commented on in the deepening of the present volume.

The Leadership of the Venetian Treatises in the Italian Peninsula and All Over the World

In order to gain an overview of the Venetian treatises within double-entry Italian works (in the Italian language) a detailed and complete bibliography has to be available.

To do so, the famous “Elenco cronologico delle opere di computisteria e ragioneria” (“Chronological list of commercial arithmetic and bookkeeping works”) has been gathered, which was edited by Giuseppe Cerboni and published by the Italian General Accounting Department (Cerboni, 1889). As accounting history scholars know, this volume, especially its fourth and last edition, which is the widest and the most updated, is still the largest and most complete bibliography on the issue (Coronella, 2016).1

Specifically, this volume lists all the works, manuscripts included, from Liber Abaci by Leonardo Fibonacci (1202) to 1888 (year of the end of the inquiry).

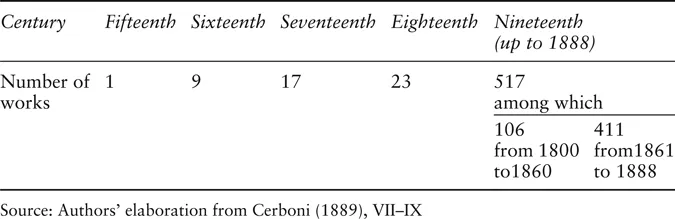

Table 1.1 Number of works on accounting divided into centuries

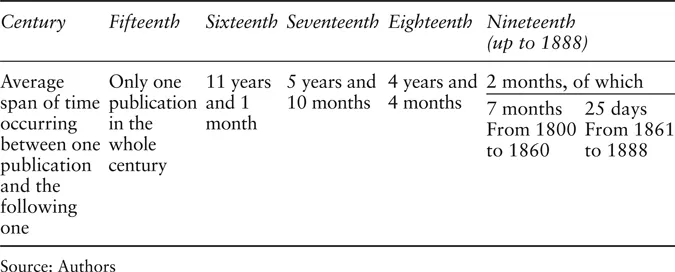

Table 1.2 Average span of time occurring between one publication and the following one

Concerning the works about double entry, the analysis of the volume underlines an exponential growth in time, as illustrated in Table 1.1.

The sense of the exponential growth of the accounting works is conceived through the analysis of the two sub-periods of the nineteenth century as preceding and following the unification of Italy (from 1861 to 1888).

In the first sixty years of the nineteenth century more than a hundred works were published—a huge increase compared to previous centuries—whereas in less than thirty years since the unification of the country more than four hundred works have been catalogued.

The relevance of these data lies in the average span of time occurring between one publication and the following one (see Table 1.2).

In the fifteenth century there is only a single printed work of accounting (the Summa by Pacioli), in the sixteenth century an average of one publication each eleven years, in the seventeenth century one nearly each six years, in the eighteenth century one every four years and a bit, in the nineteenth century up to the unification of Italy one printed work each seven months and, after the unification, one every twenty-five days—an amazing growing rate.

Therefore, up to the unification of Italy just in Venice the printed works have been listed in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Number of accounting works printed in Venice

Among the ten printed works in Italy between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (see Table 1.1) listed in Cerboni’s bibliography, eight of them (80%) are Venetian. The only exceptions are the brief essay by Gerolamo Cardano issued in Milan as a part of a work of arithmetic (Cardano, 1539) and the volume by Angelo Pietra issued in Mantua (Pietra, 1586).

The essay by Cardano consists of a brief chapter (a few pages written in Latin),3 whereas the work by Pietra is the last one issued in the sixteenth century. This means that for a long time Venice had a total “cultural monopoly” in the double-entry field (Zan, 1994, 263–264).

This perspective being strengthened, it is worth noting that in Cerboni’s bibliography a further Venetian manuscript dated 1516 (Gian Francesco, 1516) has not been listed.

In the following centuries, double entry and the related treatises spread all over the Peninsula; thus “Venetian leadership” declined as time passed.

Actually, among the several printed works in the further centuries, some Venetian ones stand out as having excellent remarks compared to the mean.

The Venetian Treatises From the Fifteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries: An Overview

The “Trattato di mercatura” (Treatise of Merchants) by Benedetto Cotrugli (1458, 1475, 1573)

As far as we know, Benedetto Cotrugli, merchant and diplomatic agent, was the first to illustrate double entry in a manuscript dated 25 August 1458.

His work, entitled “L’arte di mercatura” (The art of merchants), although written before the Summa by Pacioli, suffered the misfortune of being printed only in 1573 with the running head “Della mercatura et del mercante perfetto” (“About the essence of business practice and the proper conduct of a merchant”), moreover with several interventions compared to the original version which took place 115 years after its writing as well as 80 years after the publication of the Summa (Cotrugli, 1573).

Unfortunately, the earlier version of the manuscript has not reached the contemporary age, but information about its date is supplied by the following copies of his work (in those days, the print hadn’t been invented yet so books were copied by amanuenses or copyists). Nowadays three different manuscripts exist: the first preserved at La Valletta in the National Library of Malta, whose copy was drawn up in Naples in 1475 by Marino de Raphaeli from Ragusa; the second one preserved in the National Library of Florence and ended on 17 March 1484 by Giovanni de Matteo di Giovanni Strozzi; and a third unfinished copy (it ends at the eighteenth chapter of the third book) without any date (but dating back to the fifteenth century) and preserved in the Marucelliana Library in Florence (Coronella, 2014, 56).

The most interesting is the one from Malta, uncovered only at the end of the 1980s. The first accounting history scholars to have dealt with it are Dutch: Johanna Postma and Anne J. Van der Helm in 1998 (Postma, Van der Helm, 1998). In recent times, a thoroughly detailed work on this manuscript by Alan Sangster (Sangster, 2014) has been issued.

Before 1998, Cotrugli was referred to in the printed1573 work (composed of 106 charts),4 whose references to accounting are quite poor.

Indeed, this volume confines itself to a few pages of exposition on the accounting books for merchants and some specific entries, as well as on the closing of accounts in Chapter 13 (entitled “Dell’ordine di tenere le scritture mercantilmente” [About the correct posting of entries]) and in Chapter 19 (running head “Il saldo si deve fare ogni sette anni” [The closing ought to be carried out every seven years]) of the first book. Actually, it never delves deeper into the bookkeeping method, as Paciolo does (Peragallo, 1938, 54–55).

For this reason, accounting history scholars have rather neglected Cotrugli compared with the ampler coverage they have devoted to the Summa by Pacioli.

Nevertheless, unlike the other two already known books as well as the printed work itself, Malta’s manuscript includes a broadened appendix, which contains a patrimonial inventory and 266 ledger entries dated 1475,5 in Naples. This certainly throws a new light on the extent of Cotrugli’s work.

Moreover, it is worth noting that compared to the printed work, the various handwritten versions we know do not coincide in many aspects. The printed version largely differs, thus including deletions, amendmen...