1

Imitative Behavior in Human Neonates

Imitative acts in infants have been reported by a number of investigators. Even as early as in 1900, Preyer described imitation of adults’ lip protrusion by his 4-month-old child, an observation confirmed by McDougall (1908) who on several occasions saw that his 4-month-old child repeatedly protruded his tongue when an adult (whose face the child had been watching) made this movement.

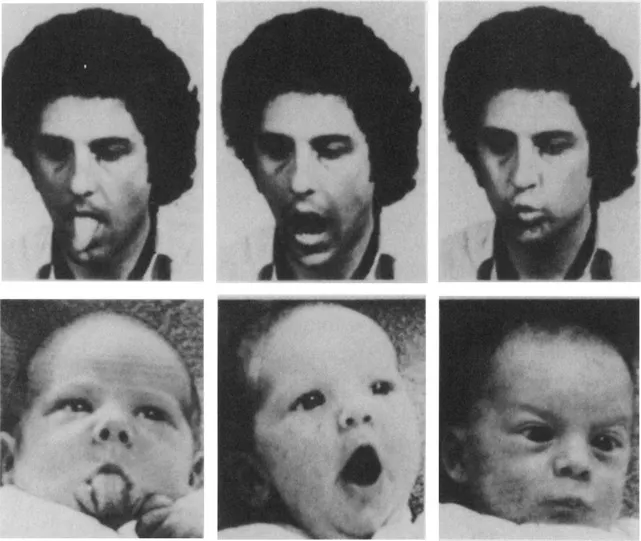

Systematic research of the problem of infant imitative behavior was undertaken seventy years later. Studies by Meltzoff and Moore (1977) showed that imitation in neonates can occur much earlier than previously reported. Specifically, 12 to 21-day-old infants were found to be already able to imitate facial expressions of an adult, such as mouth opening, tongue protrusion and lip protrusion (figure 1.1). The infants were also able to imitate manual gestures, such as hand closing and opening when these gestures were performed in the front of them by an adult. These experiments were carefully designed; the experimenters made sure that the infants had not been previously trained to imitate any of these gestures. To prevent the possibility of such training, the parents, who were present during the test, had not been told in advance about the experimental plan. Each facial or manual gesture was demonstrated to the infant by the adult four times in a 15-second presentation period. Each presentation was followed by an interval of 20 seconds, during which the behavior of the infant was closely observed and videotaped. The videotapes were then examined and evaluated by six independent volunteer judges who confirmed that imitation took place, that is, the infants did perform the movements that had been demonstrated by the adult.

FIGURE 1.1 Sample photographs from video tape recordings of 2-to 3-week-old babies imitating (a) tongue protrusion; (b) mouth-opening; and (c) lip protrusion demonstrated by an adult experimenter.

Source: Reproduced from A.N. Meltzoff and M.K. Moore “Imitation of facial and manual gestures by human neonates,” Science, 198: 75-78, 1977, by courtesy of the authors and permission from the American Association for Advancement of Science. Copyright 1977 by the AAAS.

More recently Meltzoff and Moore (1983) tested their findings on neonates of less than 72 hour of age with low illumination observations using infrared-sensitive video equipment. The video recordings were then analyzed by an observer who was not informed about gestures shown to the infants. The results showed that facial ges tures such as mouth opening and tongue protrusion were indeed imitated by neonates as young as 0.7 to 71 hours of age.

Several other investigators also reported cases of imitation of facial gestures in babies below four months of age (Dunkeld 1979) and in 2 to 10-week-old infants (Burd and Milewski 1981).

Field et al. (1982) showed that not only facial gestures but also specific facial expressions, such as happiness, sadness and surprise, presented by an adult model, can also be imitated by neonates. The study was conducted on 74 neonates at a mean 36 hours of age. During the test, the distance between the face of the adult model and the face of the infant was about 25 cm. The facial expressions of the neonate were recorded by an observer who was standing behind the model, and could see only the infant’s face but not the face of the model. There were three series of trials, one for each facial expression. Each trial was performed first when the infant looked away from the model’s face for about two seconds. An analysis of records showed that the neonates indeed imitated the model’s facial expressions such as a happy smile, sad protrusion of lips, and mouth opening suggesting surprise.

Imitation of tongue protrusion in 2 to 6-week-old infants as a response to demonstration of this act by an adult, was also reported by Jacobson (1979). The research of this author included a test as to whether tongue protrusion could also be elicited by other stimuli. Observations were conducted on 24 infants at 6, 10, and 14 weeks of age. It was found that a black pen or a white ball moving in the front of the infant also produced tongue protrusion. However, matching behavior to the tongue model declined by 12 weeks of age.

Other tests conducted by Jacobson (1979) were related to the response of hand opening and closing. It appeared that these responses could be elicited in 14-week-old infants either by hand opening and closing or by a dangling ring. A comparative analysis of the data showed that the stimuli from the human model produced higher mean number of tongue protrusions or hand closing and opening than did stimuli such as pen or ball. Moreover, some investigators reported that they were unable to replicate the data obtained by Jacobson (Burd and Milewski 1981, quoted by Field et al. 1982). According to Field et al. (1982), certain differences in experimental procedure could be responsible for this failure. Nevertheless, the observations made by Jacobson (1979) that stimuli other than those deriving from living models can also produce imitative responses are important for understanding mechanisms involved in the imitation process. These mechanisms will be discussed in theoretical comments in Chapter 11.

2

Imitation in Growing Children Under Three Years of Age

Imitative behavior in young children attracted the attention of the number of scientists early in this century. The classic studies on this topic are those of McDougall (1908), Guillaume (1926), and Piaget (1962). All these authors described a variety of cases of imitation and presented their theories of imitative behavior. Because most of the experimental data were provided by Piaget (1962), his work will be described in more detail below.

Piaget’s observations on imitative behavior made on babies and children of various age led him to postulate that the ability to imitate develops together with the individual experience acquired by the child with age. On the basis of observations made mostly on his own children, he found that there exist six stages of development of imitative behavior. Let us describe each of these stages.

Stage I: Preparation Through the Reflex

This stage includes the period of the first few days after birth. At that time the experience of the baby is very limited, and the neonate is able to imitate only the most primitive motor acts (such as those described in Chapter 1). For instance, Piaget observed that his child T., being drowsy but not actually asleep, began to cry when other babies in the same room began to wail. A few minutes later, when the baby’s father tried to imitate the baby’s interrupted whimpering, T. started to cry in earnest; other sounds, such a whistle, did not produce any reaction. The author concluded that “in neither case is there imitation but merely the starting off of a reflex by an external stimulus” (p. 7).

Stage II: Sporadic Imitation

This period includes a period from one to five months, during which the child’s experience broadens by incorporating certain new visual or acoustic elements. This results in an addition of new motor or vocal responses. For instance, in the case of suction, the baby may use new gestures, such as putting the thumb into the mouth. Several cases of vocal imitation by babies in the second month of age were also observed. For example, baby T., being awake, motionless, and silent, started to cry three times in succession, when an older child was crying; each time the baby stopped crying as soon as the older child stopped. It was also observed that the young babies more readily repeated the specific sounds produced by an adult when the adult first repeated the sound produced by the baby. Thus, when the baby made sounds such as “la,” “le,” and so on, and the adult reproduced them, the baby repeated these sounds seven times out of nine. Similar observations were also made on another child.

The same was found concerning motor responses. They were reproduced by the child more easily when the adult first repeated the baby’s motor act. However, it was found that the movement to be imitated had to be clearly visible to the baby. In the case when the movement was not distinctly visible, the imitation did not take place.

Stage III: The Beginning of Systematic Imitation

This stage includes the period between six (or earlier in some cases) and eight months of age. The observations made by Piaget at that time comprise instances of imitation of sounds belonging to the phonation of the child, and the imitation of movements the child has already made and seen. A number of cases are described in which the babies imitated the adult’s sounds such as “pfs,” “bva,” “hha,” and others. Other observations include the imitation of movements such as closing and opening the hand, when the adult repeated them several times. However, some movements of the mouth connected with eating, or movements of individual fingers, were not imitated. According to the author, these observations confirm the earlier hypothesis of Guillaume (1926) that “at this stage there is no spontaneous imitation of movements which the child cannot see himself make” (Piaget 1962, p. 29). For instance, the child can see the movements of the mouth when they are made by adults during eating, but is only aware of them in himself through kinesthetic and gustative sensations. Piaget concludes that “imitation of known sounds and visible movements proved to be lasting after a few mutual imitations, whereas imitation of nonvisible movements would have required, for its consolidation, a succession of sanctions alien to immediate assimilation” (p. 29).

Stage IV, Part 1: Imitation of Movements not Visible on the Body of the Subject

The first part of stage IV comprises the imitative behavior of the child between eighth and ninth month of age. At that time, the child is able “to assimilate the movements of others to those of his own body, even when his own movements are not visible to him” (p. 30). During this period, similarly as during the second and the third stages, the observations included mutual imitation (in which the adult first imitated a spontaneous facial movement of the child, thus producing the repetition of the same movement by the child). In a case when the baby put out her tongue and said “ba.. .ba,” the adult quickly imitated her, and she began laughing; after several repetitions of this demonstration, without any sounds by the adult, the child “moved her lips and bit them for a moments and then put out her tongue several times in succession without making any sound” (p. 31). In another case, the adult rubbed his eyes in front of child J. just after she had rubbed her eye; after several repetitions of rubbing the eyes by the adult, the child imitated this movement each time. Similar observations were made with putting a finger into the ear.

Stage IV, Part 2: Beginning of Imitation of New Auditory and Visual Models

This part describes the imitative behavior of babies between 9 and 11 months of age. However, according to the author, it is “only the fifth stage that a general method of imitation of what is new can be developed” (p. 52).

Stage V: Systematic Imitation of New Models Including the Movements Invisible to the Child

Observations at this stage were made on children from one year and one year and 3 to 4 months of age (although a few cases refer to somewhat younger or older subjects). Let us describe several examples of imitation occurring at this stage.

Imitation of visible movements includes a case when the model (father) put a sheet of paper in front of child J. (1 year and 21 days of age) and made a few pencil strokes on it and then put down the pencil. The child seized the pencil and first made several unsuccessful movements, such as trying to draw with the left hand or using the wrong end of the pencil. Finally, after the model made marks on the paper with the finger, the child at once imitated him with her finger.

Further examples of imitation at this stage include the movements connected with various parts of the body which the child could see but with which he or she is not very familiar. (1) When the model rubbed his thigh with his right hand, child J watched him, laughed, and then rubbed first her cheek and then her chest. (2) One month later, when the model struck his abdomen, the child hit the table and then her own knees. Over three months later, when the model rubbed his stomach, the child hit first her knees, and then her thigh. It was only after a further repetition of this movement by the model, two weeks later (when the child was already one year and 4V2 months old), that she correctly imitated the rubbing of the stomach by the model.

Other examples show the cases of child’s imitation of new movements connected with parts of the body not visible to the child. (1) The model touched his forehead with his forefinger; child J. (11 months old at that time) watched this with interest and then put her right forefinger on her left eye, then over her eyebrow; in the next moment she rubbed the left side of her forehead with the back of her hand, and then touched her ear and came back towards her eye. After three further trials, when the child was already one year and 16 days old, she finally seemed to discover her forehead. When the model touched his forehead, she first rubbed her eye, then touched her hair, then brought her hand down and finally put her finger on her forehead. When this demonstration was repeated on the next days, the child at once succeeded in imitating this movement and even found the approximate spot on her forehead corresponding to the spot touched by the model. (2) The model touched his nose with his forefinger; child L. (one year and 19 days old at that time) tried to imitate him at once; she raised her forefinger and moved it in the direction of her mouth; she touched her lips, then moved her hand above the mouth and, finally, she found her nose.

Stage VI: Deferred Imitation

This stage refers to the cases when the imitation does not occur immediately after the demonstration by the model, but some time later and not necessarily in the presence of the model. According to Piaget ‘s explanation, “imitation is no longer dependent on the actual action, and the child becomes capable of imitating internally a series of models in the form of images or suggestions of actions” (p. 62). Here are a few observations of this kind of imitation.

(1) Child J. (one year and 4 months old at the time) had a visit from a small boy (one year and 6 months old) who screamed when he tried to get out of a playpen and pushed it backwards, stamping his feet. Child J. never witnessed such a scene before. The next day she herself screamed in her playpen and tried to move it, stamping her foot lightly several times in succession. This was a clear imitation of the boy’s behavior.

(2) After another visit from the same boy, child J. showed imitation of another of his behaviors. Namely, “she was standing up and drew herself up with her head and shoulders thrown back and laughed loudly” (p. 63) just as the boy did during his visit.

(3) Child J. also began to reproduce some words “not at the time when they were uttered, but in similar situations, and without having previously imitated them” (p. 63).

The cases of imitation quoted above are only a few examples chosen from his book (Piaget 1962). These examples show the general methods as well as main results of his work. The method consisted of close personal observations made by the author on the subjects (mostly his own children) from their birth through the first twenty months of life. The results showed that the sporadic ability to imitate is already present in the first few months of life and it develops together with the development of the child.

Piaget’s observations were confirmed by the results of studies of other investigators. For instance, a review of research on imitation of live and televised models by young children by McCall et al. (1977) showed that infants younger than one year of age were already able to imitate simple motor behaviors with objects; the imitation of gestures was more common than the imitation of vocalization. However, the imitative ability depended on the child’s level of mental development. Children below two years of age were ...