- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Online Activism in Latin America

About this book

Online Activism in Latin America examines the innovative ways in which Latin American citizens, and Latin@s in the U.S., use the Internet to advocate for causes that they consider just. The contributions to the volume analyze citizen-launched websites, interactive platforms, postings, and group initiatives that support a wide variety of causes, ranging from human rights to disability issues, indigenous groups' struggles, environmental protection, art, poetry and activism, migrancy, and citizen participation in electoral and political processes. This collection bears witness to the early stages of a very unique and groundbreaking form of civil activism culture now growing in Latin America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Online Activism in Latin America by Hilda Chacón in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Social Aspects in Computer Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Art and Activism in Cyberspace

1 A Theater of Displacement

Staging Activism, Poetry, and Migration through a Transborder Immigrant Tool

Sergio Delgado Moya

to drive, to come, go, to cause to move, to push, to set in motion, stir up, to emit, to make, construct, produce, to lead, bring, to drive back or away, to urge, incite, to do, perform, achieve, accomplish, to take action, to do something, to work at, to be busy at, to be busy, to work, to stage (a play), to take a part in (a play), to perform (a part) in a play, to perform (in a play), to play the part of, to behave as, to pretend to be, to strive for, to carry out, execute, discharge, to manage, administer, to celebrate, observe, to spend (time), to experience, enjoy, to live, to proceed, behave, to transact, to discuss, argue, debate, to arrange, agree on, to decree, enact, to press, urge, plead, to deliver (a speech)

(“Act, v.”, Oxford English Dictionary)

It reads like a poem, the list of verbs unfurled in the Oxford English Dictionary to drive home the meanings of “act,” root word at the heart of activism. Voiced out loud, it rings exalting, a constellation of all that can be done, all that is to be done, when performing acts of activism. Most striking for someone like me, who happened on this string of words while seeking a better grasp of the meaning (the import, the substance, and significance) of activism, is the cluster of references to the world of theater, resting smack in the middle of this verbal assemblage. Striking but not surprising, given all the acting and given the high degree of staging it takes for activism to take place. Indeed, it seems like the more we embrace these two aspects of activism—the strategic and the theatrical—the more meaningfully consequent activism is. But, for reasons that are easy to rehearse (a perennial distrust of the aesthetic in general, and the poetic and the theatrical in particular; a more recently entrenched “tradition of revolutionary puritanism”1), the more playful, the more artistic, and the more beautiful aspects of activism are usually eclipsed—closeted, one might say—in order to foreground the “serious” forces at play in activist praxis and ideology.

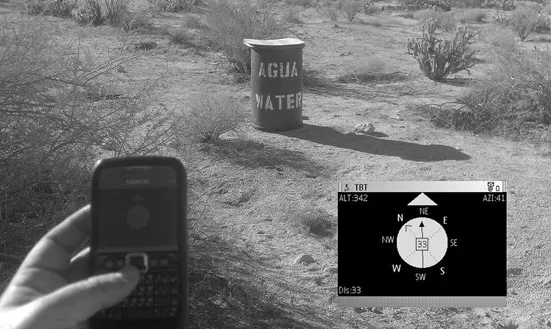

This tension between the various dimensions of activism plays out differently in the Transborder Immigrant Tool (TBT). Developed collaboratively from 2009 to 2012, a cell phone-based “code-switch” between computer code and poetry, between activism and aesthetics, the TBT is, fundamentally, an affirmation of the rights (right of passage, right to sustenance) of migrants crossing into the U.S. on foot by way of the treacherous Sonoran Desert. It is also a gesture of contestation, not just of the structures of oppression (physical, legal, technological) standing against migration, but also, and critically, against the terms under which social and political contestation have been historically registered. Not that the TBT foregrounds the theatrical or the poetic over and above the social or the political, nor that it seeks to strike a balance between them. Rather, along with the very real gesture of activism at its core, we find in the TBT a will to disturb the dividing lines that keep what is aesthetic (art, poetry) distinct from and often incompatible with what is political (social intervention, activism). We find, then, a contesting of contestation itself, articulated as an inquiry into the idea of place, staging, and framing: the place of aesthetics at large and poetry in particular and their displacement from direct actions that seek to attain a specific political or social goal; the staging of the figure of the migrant in the political imaginaries that give shape to it within a repertoire of social actors and socialized figures; and the staging of the Sonoran Desert as landscape.2 Place, stage, and landscape are here envisioned in theatrical and historical terms, through a constant play on the meaning (the sense, the substance, the import) of the notions of stage and staging.

Transbordering by Design

Developed under the auspices of two major North American research institutions,3 the TBT is a design project conceived around the idea of distributing inexpensive, GPS-enabled cell phones among migrants planning to walk across the desert that straddles the U.S. and Mexico. The cell phones have been shown in academic settings and in art exhibitions. They have been widely discussed in the media and in a wave of recent scholarly articles,4 but they have not been actually distributed among migrants.5 The phones come loaded with poems, a key feature of their design discussed at length later in this essay. They are also outfitted with locative software that can guide migrants to water posts, rescue sites, and other resources critical for survival in the trek across the desert. On a more conceptual and political level, the phones disturb the categories (the illegal, the outlaw, the undocumented, the criminal, and, increasingly, the terrorist) that have been historically used to frame images of immigrants in the U.S. The power invested in these categories goes far beyond the rhetorical. They form the basis for a series of policies6 that seek to turn migrants into social outcasts by placing them beneath the threshold of humanity we uphold when we extend humanitarian aid and other such basic provisions of human welfare (Figure 1.1).7

Figure 1.1 The TBT in operation, showing a cell phone with the Tool’s software installed and a screenshot, bottom right, from the same Nokia e71, directing the user to a Water Station Inc. water cache in the Anza Borrego Desert. Photograph and description by Brett Stalbaum.

The TBT was conceived in 2007, against a background of increasing hostility in the U.S. toward migrants, undocumented immigrants, and what Mae M. Ngai conceptualizes as “alien citizens,” U.S. born and naturalized persons rendered “permanently foreign and unassimilable to the nation” by immigration policies that racialize national, regional, and (increasingly) religious markers of certain ethnic groups (Ngai 7–8).8 The latest wave of antagonism peaked intermittently in recent decades,9 tethered as it is to the mix of social and economic indicators (economic hardship, high unemployment, spikes in inflation, stagnated wages, rising inequality) that Marcela Cerrutti and Douglas S. Massey list as conditions that “make immigration a salient political issue with the public” (Cerrutti and Massey 19). This latest wave dates back to the institution of two concerted, operational plans to quell undocumented migration at the busiest entry points of the U.S.-Mexico border: Ciudad Juárez/El Paso and Tijuana/San Diego. These widely touted plans, Operation Hold-the-Line (1993) and Operation Gatekeeper (1994), effectively militarized the borderlands extending across the urban corridors listed above. In line with other U.S. war zones established after Operation Desert Shield (1990–1991), otherwise known as the Gulf War, these plans mounted a theater of operations both visible and invisible. Visibly, U.S. border patrol agents and their motorized vehicles were positioned in prominent parts of the landscape, becoming a fixture of sorts of the borderlands as seen from either side of the border. Invisibly (or at least less visibly), an infrastructure of electronic surveillance (movement sensors, seismic sensors, low-light cameras, heat-seeking cameras,10 infrared night scopes, aircraft, etc.) of unprecedented sophistication was put in place at the border.

The objective of Operations Hold-the-Line and Gatekeeper was simple, announced to much fanfare: deter11 undocumented migration in the major entry ports (Tijuana/San Diego, Ciudad Juárez/El Paso) and move it outside urban areas, to the desert, where the border patrol believes it enjoys a “strategic advantage over would-be crossers.”12 The nature of this “strategic advantage” is grim. It rests squarely on the border patrol’s ability to force migrants onto the most dangerous, most treacherous route into the U.S.: the desert. Deterrence is the presumed effect of this “advantage,” but as Cerrutti and Massey argue on the grounds of compelling statistical evidence, Operation Hold-the-Line and Operation Gatekeeper, like every other U.S. border enforcement effort implemented since the end of the Bracero Program in 1964,13 “have had relatively small effects on the likelihood of undocumented migration between Mexico and the United States” (Cerrutti and Massey 40).14

While they fail to deter undocumented migration and while they also fail in their efforts to apprehend undocumented border crossers,15 the concerted government efforts to drive migration out of city limits and into the desert, coupled with dispersed but not entirely unrelated initiatives to dehumanize migrants by criminalizing attempts to provide them basic sustenance, do result in what Ngai theorizes as “impossible subjects,” persons outside the polis and outside the law, a “caste, unambiguously situated outside the boundaries of formal membership and social legitimacy” (Ngai 2). In short, the militarization of the U.S.–Mexico border has decimated undocumented migrants attempting to enter the U.S. on foot. And it does so with unspeakable violence. Since Operations Hold-the-Line and Gatekeeper were implemented, anywhere from a few thousand to ten thousand migrants have died in grueling desert conditions as they attempt to cross into the U.S. by foot.16 Migrants have always risked death as they make their way from Mexico into the U.S., but the number of migrants who have died after Operation Gatekeeper went into effect is appalling, without true precedent.

The rising rate of death among migrants is “strategic,” deployed from above.17 As the borderline cutting across the major urban corridors was further militarized, the path taken by a significantly large group of migrants (the most impoverished and the most vulnerable, those with little to nil financial resources or social capital) was pushed out of the urban grid and into the Sonoran Desert. And thus took shape another form of punishment, another decimation, another “removal” befallen on migrants, one that works physically as well as symbolically. Physically, because it spells death: dead bodies pile up on the grounds of the Sonoran Desert as a direct and strategic result of changes in U.S. immigration law. Symbolically, because the migrant’s death, like a path drawn on sand under the desert wind, is blurred away beyond recognition, forced out of memory and into political erasure. Briefly put, to die in the desert is, politically speaking, to die nowhere. A death unseen, unspoken,18 and un-staged is a death that never quite takes place.19 To die in the desert, then, amounts to both more and less than death: under the conditions of erasure and anonymity that so many fallen migrants have faced, death becomes more like disappearance. Without place, without background, there is no figure, there is no event, nor is there an act. Without a stage in which to set it, not even death registers. Indeed, four to ten thousand deaths have occurred in the Sonoran Desert since Operation Gatekeeper was begun, and barely a ripple has formed in the imagination of the cities and communities on either side of the border. “Quién hablaría de la soledad del desierto,” “Who would speak of the desert’s loneliness,” asks Amy Sara Carroll, citing the Chilean poet Raúl Zurita, in “Of Ecopoetics and Dislocative Media,” her introduction to the volume that prints the TBT’s working computer code alongside the project’s poetry (Carroll et al., The Transborder Immigrant Tool/La herramienta transfronteriza, 2014). Carroll’s “Desert Survival Series” poems are, in large part, a response to the silence shrouding the countless deaths in the Sonoran Desert, in much the same way that Zurita writes his own “El Desierto de Atacama”20 as a way to render the vast Chilean desert “no longer conceivable except if the voices and the deaths in the desert are made part of that desert” (Leonard Schwartz, cited in Carroll, “Of Ecopoeti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART I Art and Activism in Cyberspace

- PART II Blogging as Online Activism

- PART III Enduring Struggles, Now Online

- PART IV Cyberspace and New Citizenry Representations

- List of Contributors

- Index