- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Judgment in the Victorian Age

About this book

This volume concerns judges, judgment and judgmentalism. It studies the Victorians as judges across a range of important fields, including the legal and aesthetic spheres, and within literature. It examines how various specialist forms of judgment were conceived and operated, and how the propensity to be judgmental was viewed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Judgment in the Victorian Age by James Gregory,Daniel J.R. Grey,Annika Bautz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia británica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The judgment of the law

1

Cartes de visite and the first mass media photographic images of the English judiciary

Continuity and change

Introduction

The goal of this chapter is to explore the impact that the invention of a particular type of photographic image, the carte de visite, had on visual images of the judiciary in England from the 1860s. The carte de visite is widely regarded as an innovation that helped widen access to photography. It is also associated with the birth of photography as a form of mass media. Evidence that the English judiciary were caught up in the frenzy of production and consumption that accompanied these developments, what contemporary commentators called ‘carteomania’ and ‘cardomania’,1 is to be found in a number of sources. A catalogue dating from 1866, the height of the ‘carteomania’ craze, entitled ‘Carte de Visite Portraits of the Royal Family Eminent and Celebrated Persons’ lists over 1,000 different cartes, the vast majority of which are portraits.2 Included in the list are portraits of judges; Lord Chancellors, Chief Justices and Justices of the High Courts. They sit alongside members of the royal families of various nations beginning with Queen Victoria and her large extended family, Lords, Ladies, Dukes, Duchesses, from the United Kingdom and beyond, members of the clergy (particularly bishops), military figures (domestic and overseas) and politicians. Artists (past and present), theatre and music hall performers, sporting personalities and beauties are also prominent. Another source of evidence is London’s National Portrait Gallery. A search of the Gallery’s collection of portraits of senior English judges in post between 1860, the start of the ‘carteomania’ craze, and the early 1880s, when the carte format was superseded, reveals many carte portraits. In numerous cases cartes de visite are the only photographic portraits of the judicial sitters in the Gallery’s collection. In several cases there are multiple carte de visite portraits of the same sitter in different poses, all of which date from the same time.3 Another archive, the library of one of the Inns of Court, Lincoln’s Inn, also has a collection of over 400 such portraits in several albums that date from the 1860s to 1870s. Many sitters are judges, and some appear several times in different (but nonetheless very similar) carte portraits.4 While this is far from being a systematic survey of the appearance of the judiciary within the format, it does point to a degree of judicial engagement with this new type of portraiture.

The goal of this chapter is to examine some of the effects that the encounter between the English judiciary and the technological and media innovations that come together in this format had upon the visual representation of the judiciary in the nineteenth century. How, if at all, did this encounter affect what appears within the frame of judicial portraiture? What impact, if any, did it have on other pictures of judges? These questions will be answered by way of a case study, focusing on Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn. He became Chief Justice of Common Pleas in 1856, Chief Justice of Queens Bench in 1859 and in 1875 he took up the post of Lord Chief Justice in the newly reformed courts. He died in post in 1880.

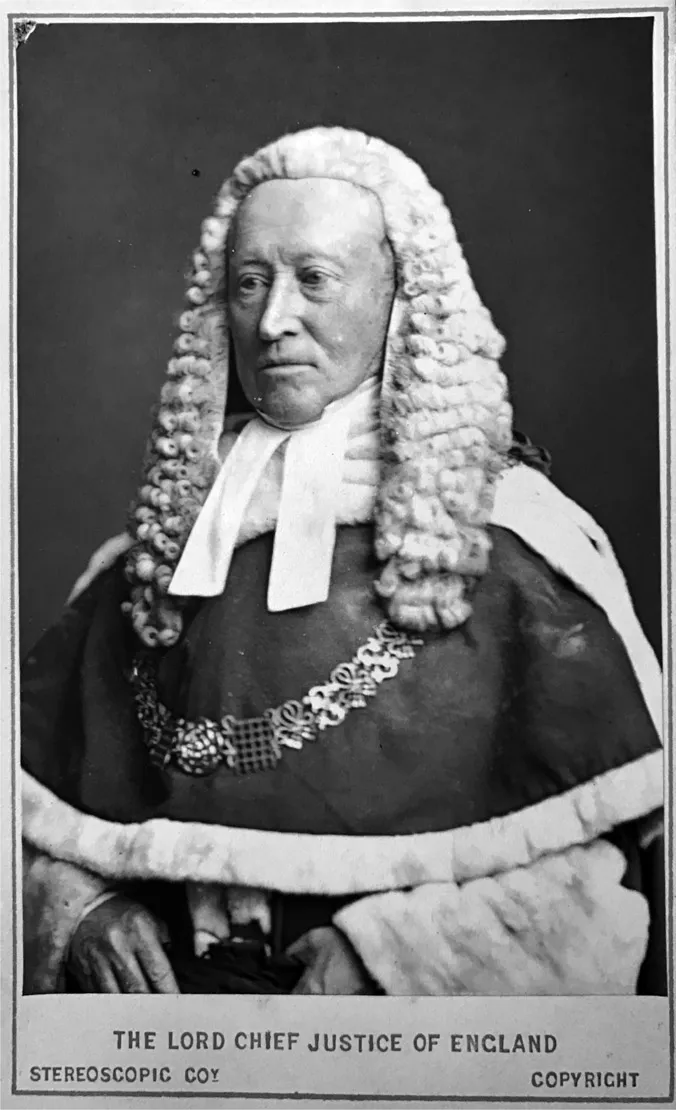

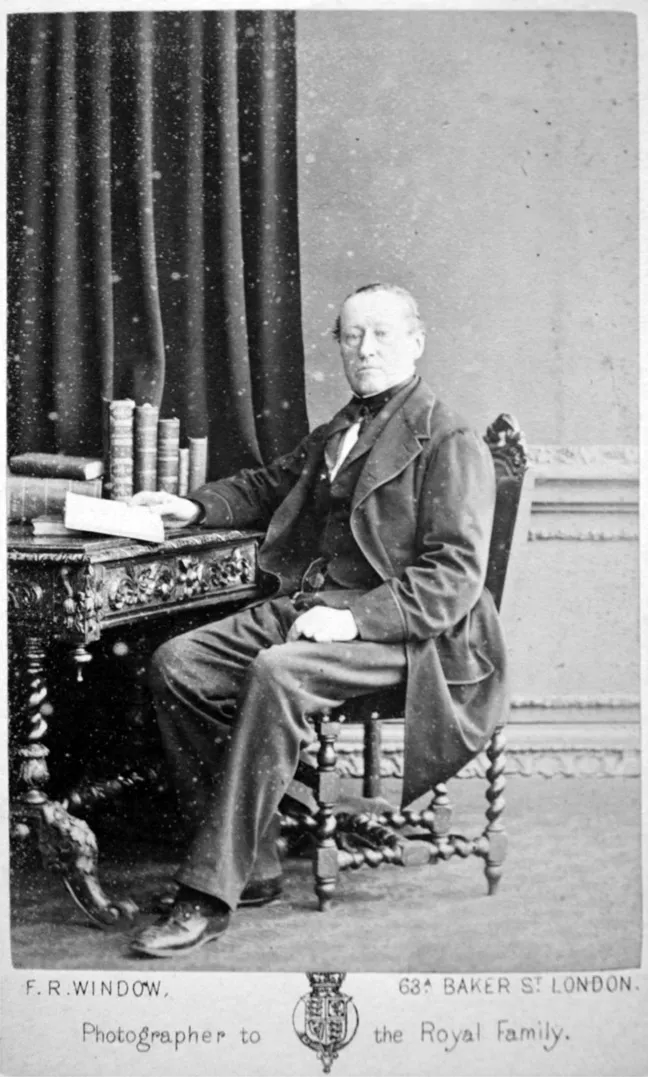

Many portraits of Cockburn were produced during his lifetime. London’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) has eleven portraits of him in its collection.5 All are dated as being produced during the period 1860–1880. The majority of these, six portraits, are photographs. Five are carte photographic portraits. Four, all showing him in his ceremonial robes, were produced by one studio, the London Stereoscopic Company. All are dated ‘circa 1873’.6 It is difficult to differentiate one from another: there is little variation between them. The many similarities, the pose, costume, props, lighting, backdrop, physical characteristics of the sitter, suggest they could well have been produced in a single sitting. The remaining carte portrait shows him in civilian clothing. He is also shown in civilian dress in the final photographic portrait which is in the slightly larger format known as a ‘cabinet card’ popularized in the late 1870s. The remaining portraits, all of which show Cockburn in his robes of office, are made using a variety of other methods. One is an undated painted portrait by Alexander Davis Cooper. A second portrait, a black-and-white mezzotint is the work of the engraver Thomas Lewis Atkinson and is dated 1871. A caricature by Carlo Pellegrini that was published by the society magazine Vanity Fair is from 1869.7 All incorporate captions: ‘The Lord Chief Justice’. The remaining two portraits take the form of sketches of Cockburn on the bench made by Sir Leslie Ward, another well-known caricaturist who worked for Vanity Fair. They date from 1873 through 1874.

The carte portraits of Cockburn in the NPG collection are not unique to that archive. Examples are also to be found in other collections in a variety of locations. I have found them for example in the library of Lincoln’s Inn in London, the State Library of New South Wales in Australia,8 and in the John Rathbone Oliver Criminological Collection of the Harvard Medical Library.9 A search of eBay or a Google Image search generates other copies of these, plus other carte portraits of Cockburn not replicated in any of these collections. In some he wears the robes of office, in others he is dressed in civilian clothing. At times it is difficult to differentiate one regalia or civil dress portrait from another. But they can be separated by way of minor variations of composition, for example offering a three-quarter body pose in judicial robes rather than a half body, or in those in which he is in civilian dress. In addition to different variations of pose they can be separated by reference to minor changes in his clothing; in some his cravat tie has a polka dot pattern in others it is striped. Props also show slight variation; some desks and chairs are more elaborate than others.

The carte shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2 will be used to examine the impact that the technological innovations that come together in this form of photography had on what appears within the frame of these two portraits of Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn about the time he was ‘The Lord Chief Justice’. Both are from my own collection. Figure 1.1 is an example of one of the many variations in which Cockburn poses in his robes of office. It also appears in all of the archives referred to above. Figure 1.2 is an example of a carte portrait in which Cockburn is portrayed in civilian dress.10

Both cartes follow the standard format. They are approximately 89 mm × 58 mm (3 1/2 in. × 2 1/4 in.) which is about the size of a visiting card. Each one is made up of a thin photographic paper print mounted on card. In common with many such portraits the robed portrait includes the name of the studio that produced the portrait on the front: ‘Stereoscopic Coy’, an abbreviated reference to the ‘The London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company’. Both cartes carry the branding of the studio on the back of the card mount. The civilian dress portrait was produced by the F. R. Window studio.11

Before embarking on the analysis of what appears within the frame of these portraits, drawing on some of the scholarship on cartes de visite, I want to add some background detail about the nature, production and impact of this type of picture.

Introducing cartes de visite

The carte de visite is a photographic picture that came into being during the 1850s as a result of new developments in chemistry and camera optics. The chemical innovation known as the albumen print process enabled the production of the first cheap and relatively easy to use, commercially viable method of producing a photographic print from a negative plate on to paper.12 The other key invention occurred in 1854 when a multiple-lens camera was patented by an enterprising French photographer, Andre Adolphe Eugene Disdéri. Different lenses could be opened to the light at different times to capture the sitter in a variety of poses on a single negative in a single sitting. Together these developments enabled the production of a photograph (and more specifically a photographic portrait) at a fraction of the cost of any other method of portraiture.13 The repeated use of the negative also allowed for the manufacture of an almost endless supply of copies of the portraits. The carte de visite was introduced into England in 1857.

The lower costs of production of carte portraits potentially widened access to portraiture for purposes of self-fashioning by those in society who had sufficient disposable income to expend on this new picture format. As such, cartes enabled and enhanced the capacity of individuals to make and shape their visibility in wider society.14 Scholars have described this as the democratizing effect of this photographic format.15 The format also introduced a much cheaper means of producing multiple copies of individual portraits for circulation.

Figure 1.1 Carte de visite of Lord Chief Justice Cockburn in his robes of office, by the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company.

Source: Author’s collection.

Figure 1.2 Carte de visite of Lord Chief Justice Cockburn in civilian dress, studio of F.R. Window.

Source: Author’s collection.

By the mid-1860s, the height of the ‘carteomania’ craze, there were 300 studios producing carte de visite portraits in London; 35 were on one street in the West End, Regent Street.16 One estimate is that between 300 million and 400 million cartes were sold in England between 1862 and 1866.17 Individuals with enough disposable income commissioned studios to make their portraits for distribution to family and friends. This is described as the primary market. Some portraits, such as those in the carte de visite catalogue referred to above, were commissioned by the studios for sale to members of the public with an interest in the sitter and sufficient surplus income to indulge their curiosity. Studios were proactive in offering their services for free to sitters with an established or emerging public profile. Scholars describe this as the secondary market.18 Hacking explains that this market was driven by the zealous pursuit of established members of the elite and other contemporary eminent and famous people by studios for purposes of their commercial exploitation.19

Carte portraits that were for sale to the public appeared in window displays surrounding the entrance to the studios. These were also spaces used to advertise the services of the studio to potential clients.20 Other outlets for cartes included fine art dealers, booksellers and stationary stores. Prices for cartes in the secondary m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I The judgment of the law

- PART II Judgments in culture

- Index