![]()

1 Introduction

Knowledge is Power.

Francis Bacon (1561–1626)

This book revolves around the connections that exist between foreign policy motivations and the provision of development assistance (a.k.a. ‘foreign aid’). It seeks to understand countries’ choices to give aid in light of their foreign policy goals. The main puzzle this research is concerned with is why a country would choose to emphasize technical cooperation – essentially the exchange of knowledge and know-how – in its provision of development assistance, particularly through unconditional and untied agreements. Simply put: what is the (foreign policy) logic behind giving knowledge with no strings attached? To answer this question, it looks at Brazil and its provision of development assistance mostly through unconditional and united technical cooperation agreements.

Technical cooperation has a fundamental place in the realm of development assistance. Initially known as ‘technical assistance’,1 it was the very first instrument used for the explicit purpose of helping other countries develop. Compared to grants and loans, a sustained policy of providing technical cooperation is relatively easier, and viable to a greater number of (potential) donor countries. Because every country has some unique knowledge (particular experience or ingenious solution) to share, and many countries face similar issues, it is safe to say most countries in the world – both developed and developing – have provided some type of knowledge to another country via technical cooperation at least at some point in their history.

While there has been more visibility of the technical cooperation flowing from developed countries to developing countries, there is a plethora of under-reported and understudied technical cooperation agreements that occur between developing countries themselves. There is growing assurance that developing countries, as a group, have an entire range of modern technical competencies. Centres of excellence in key areas have increased national and collective self-reliance, and there is concrete ‘South-grown’ expertise to be shared (World Bank, 2008; UN-GA, 2009).

Most developing countries tend to deal with similar problems (e.g., poverty; inequality; high child mortality rates), and some might ‘bond’ over particular situations, such as: countries that share related environmental characteristics or concerns, like rising sea levels; neighbouring countries handling trans-border problems (e.g., drug trafficking); or countries dealing with delicate issues related to a particular cultural or historical background, such as post-conflict reconstruction, etc. Existing examples of this South-South Cooperation (SSC) include: the agreement between Costa Rica, Bhutan, and Benin to share knowledge over sustainable tropical forest management; Kenya’s help to South Sudan in developing technical capacity to run the new government; and not to mention the immense volume of initiatives undertaken in the past decade by Brazil, China, and India with other ‘Southern’ countries. Because of these features, technical cooperation can be seen as a ubiquitous feature in the provision of development assistance.

Paradoxically though, technical cooperation is not a topic of great investigation in the literature concerning development assistance. Most of the academic attention goes to money-based mechanisms, such as grants, loans, debt forgiveness, etc. Some elements inherent to technical cooperation might be at fault for this, with two of them deserving special attention. First, these agreements tend to be characterized by small scope, breadth, and budget. When compared to financial assistance mechanisms, technical cooperation is poised to have a much more limited capacity to effectively help a country develop. So, while these agreements can be useful for helping to overcome some specific problem, or fill a knowledge gap in some area, they (typically) have a narrow capacity to leverage broad transformations. Second, technical cooperation agreements generally involve non-controversial topics, which tend to fly under the radar of most political debates, media coverage, or public interest. Hence, by themselves, each agreement generally has little reach, limited potential for structural changes in the recipient’s development, and low visibility.

But despite these ‘weaknesses’, technical cooperation agreements still continue to be part of almost all countries’ foreign policy mechanisms for providing development assistance. There are four main possibilities for why technical cooperation is such a ubiquitous part of development assistance. While the motives are non-exclusionary, it is common that some (or one) reason will be more prevalent than the others in guiding a country’s decision to offer technical cooperation. First, due to its continuous use as a mechanism for providing ‘foreign aid’, offering technical cooperation has become intrinsic to the idea of providing development assistance itself: it is used because ‘everyone who is a donor offers it’ and ‘it’s always been done’. Second, for most developing countries that want to provide development assistance, technical cooperation is probably the only option available for nations with few resources, which simply can’t offer much else to others even if they wanted to (except for an occasional help in emergency situations): ‘we can only offer technical cooperation’. Third, technical cooperation might be used because it develops. Under this logic, sharing knowledge promotes best practices and real solutions. In this case, there is an underlying altruistic bent: ‘it is offered because it works’ and ‘it helps the recipient’s development’. The fourth reason – the one which will be explored in depth in this research – is providing technical cooperation to gain something in return.

The first two motives only concern the donor, as it asks itself ‘what can I provide [in the context of development assistance]’? The next two involve thinking about the nature of the relationship with the recipient: ‘what do I, as a donor, expect from providing technical cooperation?’ – the question this book is most interested in. There is a great deal of academic debate over the broad theme of why give ‘foreign aid’ in the first place (which will be explored in Chapter 2). The present accepts that countries might be motivated to offer technical cooperation for purely altruistic reasons. However, it assumes that most donors’ initiatives are attached to some interest: donors do in fact seek to gain something from recipients when they agree to provide technical cooperation (even if it is not publicly admitted).

The idea that countries’ foreign policies are motivated by ‘gaining power’ and that they seek to support ‘the national interest’ is not new (Morgenthau, 1962; Hook, 1995). But countries can want different things out of their development initiatives, so these answers are not sufficient. Therefore, the question becomes ‘if donors want to gain something, what kind of gain are they looking for’? Assuming there are different types of gains which could be accrued, allows for a yet deeper layer of analysis: ‘what leads donors to tend to prioritize one type of gain over other(s)’? These two questions are original and relevant, and follow Wendt’s (1999:133) call for more empirical research be done to investigate “what kinds of interests state actors actually have”.

This book begins by positing a parsimonious approach towards self-interests sought from providing development assistance in general and technical cooperation in particular, dividing it into two basic categories: commercial and diplomatic gains. The former is straightforward: the primacy is to accrue profits for the donor country. Thus, ‘commercial gains’ involve seeking concrete returns – making money – through the process of selling/buying goods and services. ‘Diplomatic gains’, on the other hand, will be the term used to designate a broad range of gains that are mostly intangible (albeit very much real and sought-after in foreign policy), and harder to be secured (as they are usually based upon a social element of gratitude and/or recognition). As Chapter 2 will detail, they are related to the concepts of ‘soft power’ (Nye, 1990a, 1990b, 2004, 2011) and ‘middle power diplomacy’ (Evans, 1989, 2011; Evans & Grant, 1991, 1995; Cooper et al., 1993). Examples of diplomatic gains to the donor State include:

-

recipient’s votes and/or implicit support for the donor in international fora;

-

donor’s improved regional/international image as a ‘do-gooder’;

-

strengthened bilateral/regional relations between donor and recipient(s);

-

donor’s increased regional/international legitimacy as a necessary voice regarding a certain topic, etc.

It is important to highlight an important boundary: the present analysis is concerned mainly about gains for the State, not for the individual actor engaged in the policy. This means it consciously brackets the analysis of policymakers motivated by personal monetary gains (in the form of bribes or side-payments). Also, the word ‘diplomatic’ has been chosen over ‘political [gains]’ in order to highlight the focus on the State, foreign policy, and the international context. Nonetheless, significant connections between national and international politics are taken into consideration, as domestic normative and institutional factors inform foreign policymaking in a “two-level” process decision-makers are simultaneously engaged (Putnam, 1988).

For this book, it is assumed that (1) donors would like to accrue both diplomatic and commercial gains from their initiatives; but (2) in each agreement, the donor can give primacy to only one of these gains, which concurrently lowers the chances of the other.2 This does not mean that the donor does not value both diplomatic and commercial gains, nor that these gains are mutually exclusive – it just means the donor must opt between what it wants more. The argument posited is that the optimal way to achieve diplomatic gains through technical cooperation is by proposing agreements that have no-strings-attached.

Development assistance instruments, in general, can be provided with or without certain characteristics: ‘conditionalities’ and/or ‘tied’ agreements. To the first point, donors can condition their provision of development assistance by demanding that the recipient promote specific institutional changes so that the aid can be provided. Conditionalities can be of political nature (like related to democracy or strengthening institutions) or have an economic focus (such as macroeconomic reforms or trade concessions), and do not need to be directly related to the effectiveness or the goal of a specific development initiative. To the second item, when donors ‘tie’ the assistance it means the recipient must purchase – exclusively from the donor – certain goods and services related to the projects. ‘Tying’ an agreement means placing clear commercial provisions that benefit the donor over a specific development-based initiative.

Each one of these ‘attachments’ is independent from one another. Each donor can choose how it wants to provide its development assistance: (1) conditional and tied; (2) unconditional and tied; (3) conditional and untied; or (4) unconditional and untied. This last combination is the one which will be detailed, and serve as a synonym for what is meant by ‘no-strings-attached’ technical cooperation.

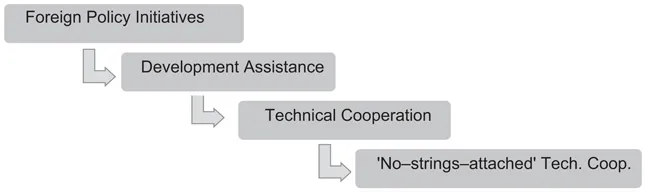

In sum, development assistance is one out of the many foreign policy initiatives a country has to achieve its goals. Development assistance can be provided by various mechanisms – one of which is technical cooperation. And technical cooperation can be arranged through different combinations: with/without conditionalities and with/without ties. This book is interested in why countries choose to provide technical cooperation agreements that have no conditionalities and no ties in the context of their foreign policy goals (Figure 1.1).

‘No-strings-attached’ technical cooperation

Conditionalities and ties always take away some level of the recipient’s autonomy, since they limit the recipient’s options. This book assumes that, ceteris paribus, recipients will tend towards a no-strings-attached arrangement. This derives from the understanding that placing conditionalities and ties onto technical cooperation agreements will reduce (although not necessarily eliminate) diplomatic gains for the donor from its interaction with the recipient.

In the case of unconditional and untied technical cooperation agreements, donors’ expectations of gains (whether commercial or diplomatic) are not formalized. This means they are not written in the agreements, and consequently they are not legally binding under International Law.3 After all, if they were binding, they would not be unconditional or untied. Of course, behind-the-scenes quid pro quo ‘commitments’ might be established. But what matters the most here is that, in these cases, there are no formal commitments made by the State, as they rely solely upon vows made between the individuals involved in the negotiation. Hence, they are not legally binding, and a recipient’s compliance cannot be explicitly demanded by the donor. This is certainly one of the reasons for the unattractiveness of a no-strings-attached arrangement – it has no ‘teeth’. It is not an ideal path for donors who seek guarantees in achieving foreign policy goals embedded in their provision of development assistance. If a donor wants the recipient to assure it will open its markets or promote democracy, having the opportunity to place conditionalities but not doing so might seem nonsensical. If the immediate gain sought by the donor through technical cooperation is a commercial one – such as selling equipment or a specific service – then untied technical cooperation is a missed opportunity.

Nonetheless, even if the donor does not ask for anything, donors generally still expect to gain something from the recipient even if nothing is open...