![]()

1 Syrian tribes

Why is it important to know about them?

Introduction

Throughout history and up to the present, tribalism continues to influence many issues related to governance, conflict and stability in the Middle East and North Africa. Many civil society advocates argue that tribal affiliation in the Middle East has diminished, as evidenced by the disappearance of intertribal conflicts. Despite this, kinship loyalties continue to play a significant role in the everyday life of the Middle East, from employment in the public sector to recruitment in the army and security apparatus to competition between families and clans for many of the government positions and other social services provided by the state. Most research on the Middle East after the Arab Spring has tended to focus on the emergence of democracy and civil society while others have focused on Islamism and Jihadism. Most recently, the Arab Spring was accompanied by the resurgence of sectarianism, extremism and other social phenomena, which at the sub- or trans-state levels, has been empowered by the weakening of states. Although tribes have also been empowered, the resurgence of tribalism was not studied deeply. Political scientists who focus their research on the political processes of the Middle East tend to concentrate on state institutions, state policies and national parties. By contrast, anthropologists who are interested in politics limit their focus to segments of communities and tribal affiliations. This book attempts to do both by relating the local patterns to the larger system of which they are part.

Throughout history, tribes have always existed alongside states. It is only in the twentieth century, with the rise of modern bureaucratic states, that tribes have become weaker as a form of organisation. In states that remained more traditional and whose economies depend more on agriculture than industry, however, tribes continued to have power and influence. After the departure of the old imperial powers from the Middle East and the rise of the nation-states, many governments in the region sought different means to bring the tribes under their control. Government officials justified their policies in different ways, starting from the mobility of the tribes which challenges the borders between states, to the tribes’ loyalty to their kin groups instead of the state and finishing with the tribes’ military capacity that has proved challenging to the state authorities over time. There are many examples of the tribes becoming strong enough not only to occupy large territories within the state but even to set up their own states. Lancaster (1981) describes the state-like nature of the Rwalla tribe in Syria. Lewis (1987) records a similar attempt in 1929 by the leader of the Fad’an tribe who announced his own state in the governorate of Raqqa.

The tribal regions in Syria that constitute 70% of the country’s landmass have been the scene of recurrent political struggles between the Arab tribes and the central state. This political struggle has manifested itself in different forms, ranging from direct military confrontation to co-optation. The main feature of tribal society studied in this book is extended kinship and family ties that influence the role of the tribe vis-à-vis the central state. To understand the role of the tribes and their influence on Syria’s stability and instability, it is necessary to explore the roots of this issue in the state’s formative years which start with the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the mandate period and the establishment of the first nation-state in 1947. It is also necessary to analyse the structure of the Syrian state and the process of tribal integration into the state system, showing how the creation of the modern state influenced the role of the tribes and how the tribes, in their turn, played a major role in stabilising the Syrian state and destabilising it at a later stage.

The importance of the book and the questions that it seeks to answer

The significance of this study stems from different factors. Firstly, after the Arab Spring that was followed by fierce civil wars in Libya, Yemen and Syria, it was clear that many of the events in those countries were motivated by tribal tendencies (Boutaleb, 2012). The Libyan, Yemeni and Syrian cases provide exemplary models of the phenomena of the resurgence of tribalism in the arena of political action in the Middle East. In the Syrian case particularly, both the Syrian regime and the opposition forces have been working since the early days of the uprising to mobilise the tribes on their side. Understanding and analysing the status of the tribe and its role in the recent uprisings/civil wars will enable the reader to access data on the most important social and political events in the Middle East which suffer from a marked deficiency of study. Secondly, tribalism has proved remarkably enduring. The creation of the modern state in the Middle East certainly posed a serious threat to tribal identity and structure in the region (Fattah, 2010). The threats were numerous in the Syrian case and included methods such as drawing the administrative boundaries of the state, settlement projects for the tribes, abolishment of the tribal legal system and the centralisation of power in the hands of government officials supported by a large military body. Despite these measures and after decades of state formation in the region, tribal identity has not disappeared. Rather, it continued to thrive while changing to adapt to the modern world. This book looks to understand why tribal culture still persists in the modern political system of Syria which will complement other prior studies on state formation in the Middle East and the dilemmas of the state system in the region. Thirdly, while the persistence of tribalism remained a puzzling issue for many researchers, the persistence of authoritarianism in the Middle East has been a more complex issue for them. While some authors focus on the role of coercive apparatus in preserving Arab authoritarian regimes, others talk about the role of international support in keeping authoritarianisms in power (Bellin, 2004; Ghalioun and Costopoulos, 2004). Very few, such as Alon (2009), have analysed how authoritarian regimes ‘incorporated tribalism into the political order’ to extend their legitimacy and survival (p. 2). Therefore this book, by focusing on how tribalism was one of the factors that secured the regime’s survival in Syria, will contribute to a wider research area on the factors that led to the persistence of authoritarianism in the Middle East. Fourthly, the new states that emerged in the Middle East in the twentieth century had to accept new borders that had not existed before; however, some states continued to treat the citizens of their neighbouring countries as part of their own constituencies (Khoury and Kostiner, 1991). Because of the blood ties that existed between the tribes of Syria and those in Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Jordan, these countries continued to extend their influence in to Syria. By showing how different countries in the Middle East have meddled in the affairs of others because of and through kinship bonds, this study will contribute to other studies on the malfunction of the Arab states’ system and other issues associated with sovereignty and the mandate countries’ division of the Middle East.

This book aims to explore the policies of the successive Syrian governments towards the Arab tribes and their reactions to these policies and the consequences for the relationship between state and tribe, from the fall of the Ottoman Empire and its withdrawal from Syria in 1916 until the eruption of the Syrian civil war. The book develops a new understanding of the linkages between environment, economy and government policies as they affect the tribes and their relationship with the state. It seeks to answer the following questions:

• What was the policy of the state towards the tribes and how did they react to it?

• What kind of relationship existed between the state and tribal leaders?

• How did it affect the political role of the tribes in Syria until recently?

• How did management or incorporation of the tribes facilitate regime consolidation or state formation?

• How did the state policies towards the Kurds and the Islamists affect the position of the tribes in Syria?

• What role do the tribes play in the current uprising/civil war in Syria?

Geography and population

Geography

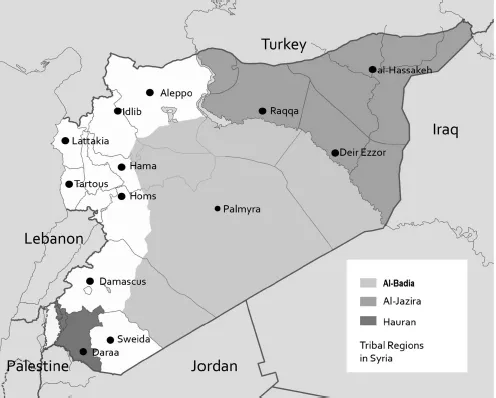

The tribes studied in this book inhabit four geographical regions of Syria. These four regions include al-Badia (Arabic: ‘the Steppe’), al-Jazira (Arabic: ‘the Island’), Hauran and the Syrian part of the Golan Heights in the countryside of Quneitra. These four regions will be known as ‘the tribal regions’ in this study. Each of these regions will be described briefly below:

Map 1.1 Tribal regions in Syria.

Al-Badia stretches over an area of 10 million hectares which constitutes 40% of the country’s land area, and it extends over large parts of central and eastern Syria (IFAD, 2012). Its administrative borders include parts of the governorate of Deir Ezzor to the east, parts of the governorates of Raqqa, Aleppo and Idlib to the north, and parts of the governorate of Hama, the countryside of Damascus, Homs and As-Suwayda to the west and south of the country. The northern border of al-Badia is marked by the Euphrates River. The Syrian Steppe is a continuation of the arid Arabian Plateau extending in an arc from the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf (Chatty, 1986). The Syrian Steppe is a dry area with low rainfall and poor quality soils that is principally used for providing pasture for the livestock of the tribes (FAO, 2004). Several important oases are located in the Steppe such as Palmyra and Sukhnah (Shoup, 1990). These oases are important centres for irrigated agriculture and trade with the tribes.

North of the Euphrates River lies the fertile region called al-Jazira. It was given the name of The Island because it is located between the Euphrates River to the east and the Tigris River to the west. It extends over parts of the governorates of Deir Ezzor and Raqqa and dominates most of the areas in the governorate of al-Hassakeh. It covers 20% of the country’s land area and is characterised by a flat geography, which spreads across a large swathe of the Euphrates River Basin, as well as the Khabur and Tigris River Basins (Mhanna, 2013). The area has historically been inhabited by Arab and Kurdish nomadic tribes. Over time, the majority of them settled down and started practising agriculture. The region produced large amounts of wheat, cotton and barley in addition to holding large reserves of oil (Ababsa, 2009). The region receives an average annual rainfall of 200–250 millimetres which allows agriculture to be more productive here than in al-Badia.

Hauran is the name of the fertile plains near the Jordanian border and the frontier with Israel. It stretches over the governorates of Sweida, Dar’a and parts of Quneitra. The majority of its population work in agriculture. In the nineteenth century most of the inhabitants of Hauran were the descendants of Bedouin (Toth, 2006). Hauran is a region of settled Bedouin (Chatty, 2014). Tribal affiliation is widespread in Hauran and is a source of identity and pride for the majority of its inhabitants. The Syrian part of the Golan Heights is situated in southern Syria, bordering the countries of Lebanon, Jordan and Israel, the Syrian governorates of Daraa and the countryside of Damascus. This area has supported agricultural activities such as wheat growing and pastoralism (Bromiley, 1994). After the 1967 war between Israel and Syria, the Golan Heights were divided between the two countries. Nearly all members of the al-Fadl tribe were displaced from their villages in the Golan Heights and mainly settled in the countryside of Damascus since then. Members of the Nuim tribe in the Syrian part of the Golan Heights have continued to live in their villages up until now.

Population

One of the factors leading to the confusion about the number of Bedouin in Syria is the fact that the term ‘Bedouin’ is used to describe settled and semi-settled nomadic groups (Nahedh, 1989). ‘Bedouin’ continues to be used for any individual with a nomadic background. Semantically speaking, ‘Bedouin’ is derived from the Arabic badawi, which is usually interpreted as ‘desert dweller’ (Cole, 2003). The Arabic word for nomadism, badawa, derives from the root b-d-w. It means the way of life and living in the desert, the opposite of settled life (Jabbur, 1995). Badu is an antonym of ‘sedentary’, ‘urban’, which is ‘hadr’ in Arabic. I will use the phrase ‘Arab tribes’ in my book because it is more acceptable among the different segments of the tribes in Syria. While interviewing people from Hauran, they refused to be called Bedouin because they have always been farmers, according to them. Many interviewees from the al-Jazira region also refused to be called Bedouin because they are Shawi (non-‘noble’ tribes). Even many interviewees of al-Badia insisted that they are ‘Arab tribes’ rather than Bedouin.

Historically, Syria’s nomadic population has been declining, going from 13% of the total population in 1930, to 7% in 1953 and less than 1% in 1982, yet tribal authority and solidarity proved capable of surviving in changing conditions, i.e. agricultural settlement or urbanisation (Hinnebusch, 1989). The previous spokesman for the coalition of the tribes in Syria, Mahmoud al-Dougeim, stated that the tribes constitute 55% of the social structure of the country, and even the Kurds and Turkmens are organised into tribal structures (Abu-Zayd, 2013). The Alawites are divided into four major tribes: the Khayyatin, Hadadin, Kalblya and Matawira (Firro, 2005). The Druze are divided into three major tribes: al-Atrash, al-Amer and al-Hinidi (Interviewee 1, 2015). The Kurds are divided into many tribes, some of which are Amikan, Biyan, Sheikan and Jumus (Tejel, 2008). Although the Alawites and the Druzes are tribally organised, their sectarian identity remains predominant and stronger than their tribal identity. The same could be said about the Kurds whose ethnic identity is stronger than their tribal identity, which is why these three groups are not included in the scope of this book (al-Ayed, 2015).

Syria’s population reached 24.5 million in January 2011 (Central Office for Statistics, 2011). Out of this population, 1.7 million live in Deir Ezzor, 1.0 million in Raqqa, 1.6 million in al-Hassakeh and 1.1 million in Dar’a (ibid.). If we exclude the Kurds from these statistics, we could say that 80% (3.4 million) of people living in these governorates belong to Arab tribes. Additionally, 10% (1.3 million) of the citizens live in the governorates of Aleppo, Idlib, Homs, Hama and Quneitra who, according to the same source, number 4.5 million in Aleppo, 2.1 million in Homs, 2.1 million in Hama, 2.1 million in Idlib and half a million in Quneitra. The total number of people who are members of Arab tribes would, by this count, be 4.7 million. This means that Arab tribes’ population in Syria would amount to 19.34% of the whole population living in a region that covers 70% of Syria’s total land area. This number is very close to the statistics (15%) of Chatty (2013) and the Syrian researcher Abdul-Nasser Al-Ayed (2015) who published a few studies on the role of the tribes in the Syrian conflict.

The tribes used to live in portable, black tents made from woven goat hair and they moved from one area to another looking for grass and water for their herds (Elphinston, 1945). More permanent settlements have only played a minor role in the tribes’ survival, though they have had relations with cities and their markets in order to sell their products and to procure daily necessities (Marx, 2006). The primary economic activity of the tribes was, and to a certain extent still is, animal husbandry through the natural grazing of sheep, goats and camels (Jabbur, 1995). Tribes have usually spoken Arabic dialects that differ from those spoken in urban centres (Cole, 2003). ...