![]()

1 Nuclear energy and the management of radioactive waste

Nuclear energy is a major source of energy. It supplies about 14% of electricity in the world, more than 18% in OECD countries and approximately 30% in the European Union (EU) (Garwin 2013; NEA 2017). The nuclear energy currently produced is released by a process of nuclear fission that involves the splitting of atoms using uranium (NEA 2012d). In 2017, about 450 nuclear reactors were in operation in 30 countries.1

Nuclear energy has had a difficult history, more than any other technology of the 20th century. Mixed feelings accompanied the discovery of radiation and fear followed the use of the atomic bomb in World War II. Nevertheless, the peaceful application of nuclear energy that started in the 1950s was met with initial enthusiasm. Only through the decades, particularly after the 1970s, the general support for this source of energy has faded as a result of major accidents, safety issues and the problematic management of its waste.

This chapter introduces the topic of radioactive waste management (RWM). It offers a brief historical overview on the major developments of nuclear energy2 and touches upon the concerns that this form of energy has raised over time. The chapter discusses, then, the role of nuclear energy in a low-carbon economy and society, and its current challenges in terms of safety and, more extensively, RWM. The chapter also explains the distinction between low-, intermediate- and high-level radioactive waste, and touches upon deep geological disposal as the ultimate solution for high-level waste. Finally, the chapter presents Directive 2011/70/Euratom and its call for transparency in RWM in the EU.

Looking backward: a brief history of nuclear energy

Nuclear science is a relatively recent discipline that has developed over the last century. Its origin can be traced back to the late 1800s when the phenomenon of radioactivity was discovered (U.S. Department of Energy 2011; Weingart 2007). Radioactivity consists of a process by which the nucleus of an unstable atom loses energy by emitting electromagnetic waves or sub-atomic particles. This energy is called radiation (NEA 2012d). We know, now, that a specific type of radiation, i.e. ionising radiation, is capable of causing damage to living cells. In particular, the radiation generated during the production of nuclear energy has the potential to harm people and the environment if it is released accidentally (NEA 2012d). Exposure to high doses of radiation increases the chance of developing cancer; very high doses can cause immediate death (Weingart 2007). For this reason, high levels of safety are considered essential for the use of nuclear energy (NEA 2012d).

Studies and discoveries on radioactivity and radiation continued in the early 1900s. It became clear that atoms are divisible, unlike what had always been believed; they can divide and transform (or “decay”) into other elements. In particular, when uranium was bombarded with neutrons, lighter elements were produced; the missing mass had transformed into energy on the basis of Einstein’s equation (E=mc2). Nuclear fission was, thus, discovered: a neutron can cause an atomic nucleus to split and release more neutrons that cause other atoms to split in a chain reaction that generates energy in the form of heat (NEA 2012d). Atoms of many elements can be split to obtain small amounts of energy, but only uranium and plutonium can produce the neutrons needed for a self-sustained nuclear fission reaction (Garwin 2013). The nuclear age started in 1942, when Fermi conducted the first human-controlled self-sustaining nuclear fission reaction (Brook et al. 2014; U.S. Department of Energy 2011).

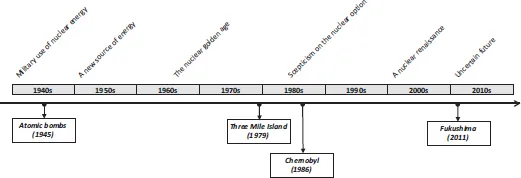

The demonstration by Fermi was immediately exploited for military application during World War II, in the framework of the “Manhattan Project”. Two atomic bombs were, later, launched in Japan in 1945 on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, marking nuclear energy’s destructive debut (Figure 1.1). In the wake of the tragic demonstration of the great atomic power released during the bombing, the international community realised the importance of harnessing such power and decided to commit to the peaceful use of nuclear energy for the benefit of mankind. As a result, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was founded in 1957 with the purpose of promoting nuclear cooperation at a global scale (Brook et al. 2014; Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015; Garwin 2013; U.S. Department of Energy 2011).

Figure 1.1 Nuclear energy: major trends and events

Source: Personal elaboration

The use of nuclear energy was, thus, diverted to the production of electricity, which started in the 1950s in several countries outside Europe (i.e. US and the ex-USSR) as well as inside (i.e. UK and France) (NEA 2012d). The nuclear power industry grew rapidly in the 1960s in many other countries around the world (e.g., Belgium, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Canada and Japan) (Chater 2005; Lester & Rosner 2009). At that time, nuclear energy was portrayed as a “miraculous and limitless form of energy” (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015; see also Garwin 2013) and a “glittering technological panacea” (Pasqualetti & Pijawka 1996).

Nuclear power generation intensified during the oil crisis of the 1970s. This period marked, nonetheless, a turning point in the history of nuclear energy (Figure 1.1). The positive attitude around nuclear power started to decrease mainly because of the economic costs of building nuclear power plants (NPPs) and the growth of anti-nuclear environmentalist movements concerned with safety issues and radioactive waste (RW) (Chater 2005; Pasqualetti & Pijawka 1996; U.S. Department of Energy 2011). At the end of the 1970s, the first major nuclear accident of Three Mile Island (1979) heavily struck the popularity of nuclear energy3 (Kasperson et al. 1988).

While public confidence in nuclear energy was still low, a second major accident occurred in Chernobyl in 1986 (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015; Chater 2005). Confidence in scientific knowledge and expertise in the field decreased. The events of Three Mile Island and Chernobyl brought the fear of atomic energy from its military application and the memories of World War II to its civilian employment (2007). As a consequence, nuclear power generation faced a period of stagnation and decline, particularly in the Western world (NEA 2012d).

In the late 1990s an apparent revival of nuclear energy – a so-called “nuclear renaissance” (NEA 2012d) – was on its way, mainly as a response to the difficulty of meeting energy demands with renewable energy sources alone, the increasing cost of fossil fuel, the dependence on foreign oil and the necessity of reducing CO2 emissions (Lester & Rosner 2009; Sundqvist & Elam 2010; Weingart 2007). The chance of a nuclear renaissance was, though, shattered by the Fukushima accident of 2011 which brought many national governments and public opinion to question the safety and use of nuclear energy (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015).

Following the third major nuclear accident of Fukushima-Daiichi, some countries have decided to freeze any nuclear development, close existing plants over the following years and turn away from nuclear energy (notably Germany and, outside the EU, Switzerland) (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015; NEA 2012d). However, several other countries are embarking on a new expansion of nuclear energy or have confirmed previous programmes of investment (e.g., UK). National policies towards nuclear energy vary across the EU depending on the national political priorities, the resources available and the technology possessed by each Member State (MS). In a world facing rising electricity demands under the need of lowering CO2 emissions through the decarbonisation of energy supplies, the nuclear option still remains attractive in terms of competitiveness of electricity production, security of supply and reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (NEA 2012d).

If we move from the political orientations of national governments to public opinion across the EU, we see that more than 40% of European citizens are in favour of nuclear power generation according to the last Eurobarometer on the topic (Eurobarometer 2008). Finland and Sweden score at the top of pro-nuclear countries, with (respectively) 61% and 62% of the population in favour of nuclear energy. Public opposition to nuclear energy is commonly due to people’s concerns about safety issues, radioactive waste (RW) and nuclear weapons proliferation4 (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015; Eurobarometer 2008; IAEA 2014).

In particular, the management of RW affects public acceptance of nuclear energy so strongly that it has been defined as the “Achilles’ heel” of nuclear power generation (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015). According to some studies (e.g., Di Nucci et al. 2015; Sundqvist & Elam 2010), a large portion of people’s opposition to nuclear power would disappear if citizens perceived that a permanent and safe solution for RW exists. Instead, a general sense of distrust populates the whole nuclear field, including RWM. The reasons for this lack – or, rather, loss – of trust must be found in the nuclear history itself.

The loss of trust

Nuclear energy has experienced a considerable loss of public trust over the decades (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015; NRC 2003). Public fear surrounds both operating nuclear installations, and facilities for the storage and disposal of RW (NEA 2003). This low level of trust can be explained as the sum of two processes, i.e. the general erosion of public trust in government and historical developments specific to the nuclear field.

As a general trend, public trust in government and public agencies has declined across all developed countries and in many policy areas (Armour 1991; Pharr & Putnam 2000; Tuler & Kasperson 2014). The unquestioning trust in authorities typical of the 1940s and 1950s has been substituted by growing citizens’ awareness, activism and scepticism since the1960s and 1970s. We live today in ‘an era of general public distrust of government’ (Weingart 2007: vii; see also OECD 2017). Several factors are responsible for this “alienation from government” (Weingart 2007): the recent prolonged economic crisis; poor performance of national administrations; episodes of dishonesty and corruption in governments; and the political inability to address current crises such as large-scale migration. This goes well beyond the nuclear field and relates to a broader political and social debate that falls outside the scope of the book.

In the nuclear field, distrust for government – and industry – is well acknowledged (Pasqualetti & Pijawka 1996). According to the Nuclear Energy Agency of the OECD (NEA 2003: 17), this lack of credibility reflects the general trend explained above. Undoubtedly, though, something specific to the nuclear field makes it highly distrusted by the general public. Multiple elements in the history of nuclear energy explain such strong distrust: the role of images; the military legacy; the production of RW; mistakes in (crisis) communication; major accidents; popular ignorance; and media intensification.

First, popular concerns about nuclear energy and RW are rooted in images of danger that predated the very discovery of nuclear power. Even before nuclear weapons and nuclear energy became a reality, the discovery of radiation was surrounded by a belief of extreme powers in the public imagery. Radiation was believed to be capable of (almost) magical effects that would go from medical miracles to destruction and horrific mutations induced in living beings (Weart 1991; 2013; Weingart 2007).

Second, the use of atomic bombs confirmed the massive destructive nature of nuclear energy. Public opposition to nuclear energy is still partly due to the fear of radiation perpetuated by memories of the nuclear weapons used during World War II and their effects. Prejudices in popular culture about radiological safety are, indeed, still very strong. The secrecy that surrounded the military use of nuclear energy before it became a source of electricity for civilian purposes contributed to these prejudices in public imagery (Brook et al. 2014; Weingart 2007).

Third, RW started to solicit greater anxieties than other types of industrial waste (Weart 1991). In the 1950s, the peaceful use of nuclear energy was still accompanied by the expectation (or hope) of a utopian future steered by nuclear innovative devices (Garwin 2013). It is in the 1970s that Weart (1991; 2013) identifies an important turning point. The fear of radiation dating back to the atomic bombs was revamped by more recent concerns for the fallouts from bomb tests. Such fear broadened, then, also to the civilian use of nuclear energy and its related waste (Weart 1991, 2013; Weingart 2007).

Fourth, feelings of fear and distrust escalated in a context of “arrogance, indifference to the public, and secrecy” shown by responsible governmental agencies and the nuclear industry (Weart 1991; 2013). The nuclear sector (both governmental and commercial organisations) can be blamed for mistakes of communication, particularly miscommunication and delayed disclosure of information during nuclear accidents (Shrader-Frechette 2015).

Fifth, three nuclear accidents – i.e. Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima – have marked a clear decrease in public trust: ‘[a]fter each major accident, the industry has suffered major setbacks with loss of public confidence’ (Brunnengräber & Schreurs 2015: 55).

Sixth, nuclea...