Introduction

Since the end of the Cold War, it has been increasingly clear that democratic institutions such as legislatures and elections paradoxically contribute to the resilience of authoritarian regimes (Gandhi and Lust-Okar 2009).1 Legislatures help authoritarian leaders to facilitate power-sharing among elites (Svolik 2012: chapter 4; Wright and Escribà-Folch 2012) and selectively co-opt challengers and opponents (Gandhi 2008). Elections also provide informational benefits to dictators by revealing the distribution of electoral support (Magaloni 2006) and the ability of elites to mobilize electoral support (Blaydes 2011; Reuter and Robertson 2012).

In particular, party-based autocracies are more resilient than other types of autocracies (personalist or military regimes) (Geddes 1999). By tying their own hands with the formal and informal rules of party politics, leaders can credibly commit to sharing power and benefits with elites and masses (Magaloni 2008). Institutionalizing a party also creates a stake in regime survival among junior cadres by exploiting their progressive ambition (Svolik 2012: chapter 6). In addition, a political party helps ruling elites to create a highly advantageous playing field by monopolizing legislative power and state resources (Magaloni 2006; Greene 2007).

However, the mere existence of a party does not assure its enduring dominance, because only a limited number of them can remain in power for a long time. Specifically, despite the aforementioned benefits, multiparty elections lower the likelihood of regime survival (Magaloni 2008: 734–6; Svolik 2012: 184–92). To understand why some parties successfully survive multiparty elections, scholars have paid increasing attention to so-called dominant parties, such as Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI (Mexico), People’s Action Party or PAP (Singapore), Kuomingtang (Taiwan), United Russia, Botswana Democratic Party, Socialist Party (Senegal), and Chama Cha Mapinduzi (Tanzania).2

In their explorations, major case-focused studies (Magaloni 2006; Greene 2007; Blaydes 2011) have frequently encountered the key role played by resource distribution. Specifically, what is crucial is not the mere dispensation of benefits but the mechanism of controlling the flow of resources so as to cause elites and masses to actively sustain or passively accept the current regime (Slater 2010: 11–12;3 Svolik 2012: 163). Despite the significance of the distributive mechanism,4 however, there have been insufficient attempts to untangle the actual flow of resources and the underlying logics.

This book fills this gap by exploring distributive strategies of the former ruling coalition in Malaysia (formerly Malaya), Barisan Nasional (BN or National Front, formerly the Alliance) led by the United Malays National Organization (UMNO).5 Many studies mention it as the key case of dominant parties (Magaloni 2006: 2, 22; Greene 2007: 16, 268–75; 2010; Reuter 2017: 1, 8).6 Although the BN defeated in the 2018 election, its resilience was outstanding in terms of its longevity and competitiveness among other dominant parties.

To explain the BN’s resilience, existing Malaysia studies have repeatedly pointed out the key role of patronage distribution (Scott 1985; Shamsul 1986; Crouch 1996; Mohammad 2006), including some quantitative analyses (e.g., Jomo and Wee 2002; Pepinsky 2007; Ahmad Zafarullah 2012). However, there is still room for further investigation of distributive strategies. By utilizing originally constructed datasets, this study examines the distributive patterns of key political resources, i.e., money (development budgets), posts (ministerial portfolios), and seats (districting and apportionment).

The central argument of this book is that efficiency in resource distribution was the key to the BN’s resilience. The book argues that the BN leaders had provided effective career incentives for elites to induce electoral mobilization with fewer budgetary resources. A limited pool of electoral support and the lack of self-financing elites induced the BN to develop such a distributive mechanism. The study also examines complementary strategies for intra/interparty conflict management to keep such an incentive mechanism intact and the efficient transformation of mobilized votes into legislative dominance. It also investigates the historical origins and decline of party dominance.

Systematic analyses reveal that the distributive mechanism found in Malaysia deviates from the mechanisms in an electoral theory or a coalitional theory of party dominance. The former (and conventional wisdom of Malaysia studies) attributes party dominance to punitive threatening and the exclusion of opposition supporters. In contrast, the latter expects rewards for autonomous and powerful elites. The problem with these theories is that the former assumes the party discipline as given, whereas the latter consider electoral support to be a secondary accompaniment of elites’ support. The study argues that this theoretical division is a diversion from the important aspect of distributive politics in Malaysia, i.e., mobilization agency.

To clarify the aim of the book, the next section demonstrates the hidden vulnerability of the BN’s dominance and argues that the conventional view (the electoral theory of party dominance, including the punishment regime theory) cannot fully explain the distributive strategies in Malaysia, because it pays insufficient attention to the incentives of ruling elites. The subsequent section discusses why the coalitional theory of party dominance is also insufficient to understanding the BN’s distributive strategy. It explains why bridging the theoretical division helps not only deepen our understanding about the Malaysian politics but also extend the theoretical scope of distributive politics studies in general. The final section explains the plan of the book.

A puzzle and the shortcomings of conventional view

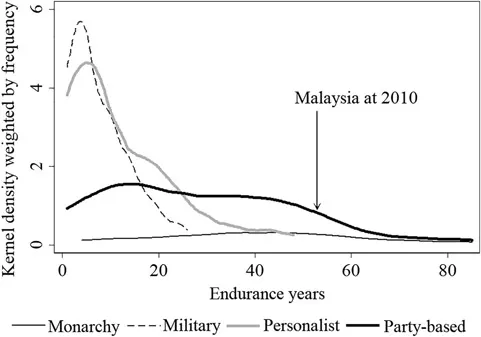

The merit in focusing on Malaysia stems partly from the outstanding resilience of the BN. As stated earlier, party-based autocracies are more durable than personalist or military regimes. Figure 1.1 illustrates the endurance years (censored at 2010) of different types of autocracies in the dataset of Geddes, Wright and Frantz (2014). It confirms the relative durability of party-based regimes and the BN’s outstanding tenure even within this category.

The longevity of party dominance allows us to examine an optimal distributive strategy for party dominance, because the longevity implies that leaders of ruling parties have/had followed an optimal distributive strategy in specific strategic conditions. A long-term reign structures “a rule of the game” that is shared implicitly or explicitly by participants including politicians, bureaucrats, interest groups, party clerks, vote-canvassers, and electorates. Continuous interaction in turn leads to the specific pattern of distributive politics.

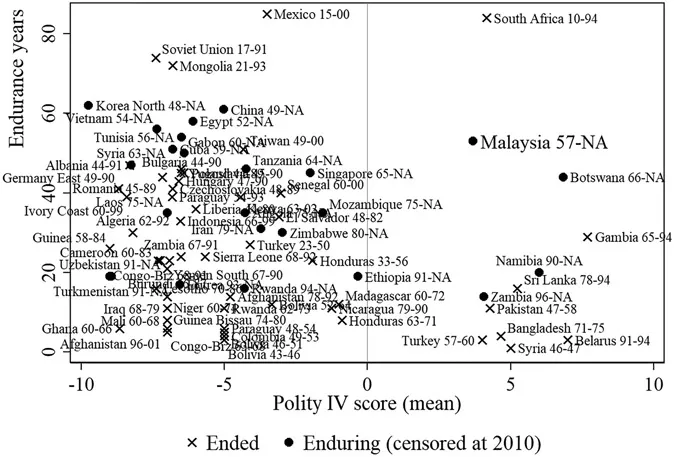

More important, the BN had survived more competitive elections than those of other cases. As seen from the scatterplot of the tenures and the mean scores of the Polity IV index during the tenures of party-based regimes (Figure 1.2),7 the degree of political competition is negatively associated with the endurance periods. It shows that the long-lasting cases are rare in relatively competitive regimes. Malaysia, for which the mean Polity IV score is 3.7 (1957–2010), is outstanding for attaining both longevity and competitiveness, as is Botswana.8

Figure 1.1 Kernel densities of duration years by regime types, 1946–2010

Figure 1.2 Scatterplot of longevity and competitiveness of party-based regimes, 1946–2010

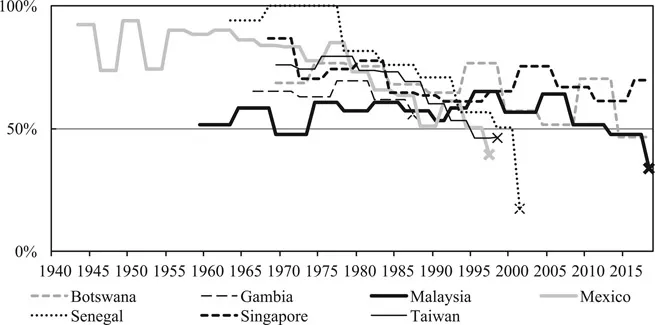

Moreover, the Alliance/BN had enjoyed merely a limited pool of electoral support. Figure 1.3 compares the trends of vote shares of leading dominant parties listed by Greene (2010). It indicates that the Alliance/BN had faced tougher competition since the embryonic (democratic) period and its vote shares have hovered at lower scores.

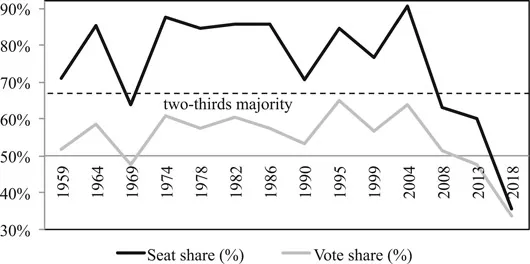

Despite the limited pool of votes, the Alliance/BN had sustained a two-thirds majority except in the 1969 and recent elections (Figure 1.4).9 A partial reason lies in electoral rule. Like Botswana, Malaysia uses a single-member, plurality electoral rule, or the first-past-the-post (FPTP), which magnifies lower vote shares into larger seat shares. Yet, at the same time, the FPTP ironically magnifies seat fluctuation by translating the modest level of decrease in vote shares into a significant number of defeating seats.10 Because the FPTP bonus (seat share minus vote share) becomes smaller as electoral performance deteriorates, the FPTP cannot provide a bulwark against electoral setbacks.

Given the electoral vulnerability of the BN, the theory of punishment regime proposed by Magaloni (2006) cannot sufficiently explain its resilience. This theory attributes the long-term party dominance to punitive threatening. According to this theory, winning a supermajority in the legislature bestows on the winner monopolistic control of state resources. The ruling party then reinforces electoral support by threatening exclusion from distributive benefits,11 which in turn deters pragmatic elites from defecting or seeking political careers outside the ruling party and imposes a serious coordination problem on opponents. Such equilibrium generates “the image of invincibility” (Magaloni 2006: 9) to reproduce party dominance.12

Figure 1.3 Vote shares of typical dominant parties, 1946–2018

Figure 1.4 Vote and seat shares of the Alliance/BN, 1959–2018 Source: Election Commission, Report on the General Election, various issues.

Existing Malaysia studies have also highlighted the monopoly of resources that enable punitive exclusion of opposition states, constituencies, localities, groups, and individuals from various kinds of benefits (e.g., Scott 1985; Shamsul 1986; Jomo and Wee 2002; Mohammad 2006). However, because of the vulnerability, a punitive logic cannot be the core of the distributive mechanism in Malaysia. A narrow and unstable support base made it difficult for the BN to rely on limited safe areas and the punitive strategy that can even consolidate a tentative oppositional swing.

Stable supporting bases for the BN had been restricted to specific parts of the peninsula (e.g., Perlis, Pahang, and Johore). Other areas, except some oppositional strongholds (e.g., Kelantan and Kuala Lumpur), had been much more vulnerable because of the limited and volatile electoral support. Although keeping the oppositional stronghold (Kelantan) in a less-developed status might have some demonstration effect, the exclusion of oppositional areas from the flow of distributive benefits had never suppressed the fluctuation of electoral support.

It is reasonable to think that the strategic condition of the BN differs substantially fro...