![]()

1 Introduction

The Eurocrisis and national political elites

Nicolò Conti, Borbála Göncz and José Real-Dato

In September 2008, the bankruptcy of Lehmann Brothers marked the beginning of the world’s worst economic and financial crisis since the Great Depression in the 1930s. In Europe, this so-called Great Recession, turned in 2010 into a sovereign debt crisis that hit severely most European Union (EU) countries and seriously threatened the foundations of the Economic Monetary Union (EMU or also informally, Eurozone). Several Eurozone countries (particularly Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain) experienced serious problems in meeting their public debt commitments – which had increased since 2009. The economic downturn due to the global crisis, which also had accentuated internal economic structural problems, provoked a reduction of government revenues and a rise in public expenditures to cope with the negative effects of the crisis. These effects were mostly related to the increase of unemployment rates and to problems of highly indebted national banking systems which required public support in order to avoid bankruptcy.

These events led to what has been called the ‘European debt crisis’ or the ‘Eurozone crisis’ (Moro 2014), which brought about not only economic stagnation and recession in EU countries, but also a crisis of confidence in the sovereign debts and, in general terms, in the European financial system where the solidity of European financial institutions started to be questioned (Hall 2014). Nevertheless, the crisis did not affect all member states to the same extent or in the same manner; many started to recover earlier, while others (particularly those most severely hit in Southern Europe) experienced greater difficulties in returning to a path of economic growth. The crisis really reflected the differences among national economies with diverse institutional characteristics (ibid.).

The economic crisis in the EU has been accompanied by political changes, both at the national and the EU level. At the national level, practically no government that was in office before the crisis was re-elected (the only exception being Germany), and many countries have witnessed an increase in political disaffection and a loss of legitimacy of their political institutions (Auel and Höing 2014; Magalhães 2014). Also, in many countries the party system has experienced important changes, mainly associated with the discrediting of mainstream parties and the rise of extremist or anti-system political alternatives (Verney and Bosco 2013; Conti and Memoli 2015; Kriesi and Pappas 2015).

At the EU level, there has been a growing public questioning of the efficacy of the EU institutional architecture in coping with this situation. Since 2010 the EU launched, in collaboration with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), some financial assistance programmes to bail out those countries that were in greater difficulty (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and later Spain).1 Measures reinforcing the economic governance of the EU and, particularly the EMU, were also introduced, though with greater difficulty. First, in 2011, the so-called ‘Six-Pack’ and ‘Two-pack’; and, in 2012, the Treaty on Stability, Coordination, and Governance (also known as ‘Fiscal Compact’).2 The measures aimed at helping countries to cope with the financial problems also included the actions taken by the European Central Bank (ECB) to support and restructure the European banking system and offer relief to countries experiencing difficulties.

These measures reinforced fiscal austerity policies in countries under already severe economic problems, reducing the ability of governments to cope with the social consequences of the crisis. Particularly, bailout programmes implied the imposition on target countries of a strict conditionality based on fiscal discipline, structural reforms and close supervision by the ‘troika’ (European Commission, the ECB and the IMF). All these actions raised public criticism since they neither guaranteed a fully economic recovery nor corrected the alleged inbuilt problems of the EMU (Stiglitz 2016). Besides, since these measures put into question the room for manoeuvre of national sovereign governments to decide their policies, they reinforced criticisms focusing on the underlying fundamentals of the European integration process itself – particularly, the conception of the EU as a unified political entity above the national interests of member states.

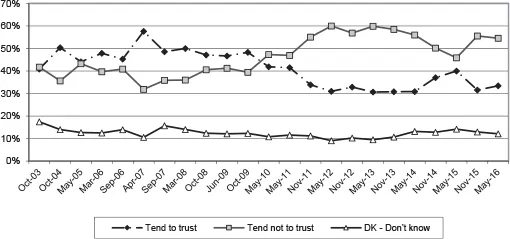

Therefore, in the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis the EU witnessed a very significant decline in public support for the European integration project in most member states (Serricchio et al. 2013). According to Eurobarometer data (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2), since June 2010 – coinciding with the first bailout of Greece – the average proportion of citizens who tended not to trust the EU has been higher than the proportion of citizens who tend to trust the EU – something not seen since the first point of the series in October 2003, some months before the big enlargement to Central and East European countries.3 Therefore, it is not an exaggeration to say that during the past years the EU has experienced one of the most important legitimacy crises in its history.

In this context, the analysis of the evolution of the attitudes of national political elites towards the EU is of particular interest. This is not only because national political elites (along with other economic and social elites) have driven the development of the European integration process since its inception (Haller 2008), but also because of their position as intermediaries between citizens and European institutions. From this position, national political elites provide citizens with cues and meaning references that they use in constructing their views of the political world surrounding them and, particularly, of political institutions (Higley and Burton 1989).

Consequently, national political elites play a key role in the process of legitimating the European integration process before their fellow citizens. This occurred both during the period when European integration was mostly an elite-driven process supported by what has been called the ‘permissive consensus’ of the public (Lindberg and Scheingold 1970); but also during more recent times, particularly since the 1990s, when this permissive consensus’ hypothesis gave way to a new context where the EU became (in some countries) a contested issue. In this ‘constraining dissensus’ scenario (Hooghe and Marks 2009), as mechanisms of democratic representation and accountability remain essentially national, domestic political elites continue to be the main mediators between their fellow citizens (who have become increasingly disenchanted about the integration process) and European institutions and decisions. In sum, exploring and tracing the views of national elites, their variety, stability and change, offers a crucial point of view for understanding the legitimacy and the future of the EU integration process, particularly during the critical juncture of the last few years.

Figure 1.1 Trust among EU citizens (average percentages for all EU member states).

Source: Eurobarometer (http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/getChart/chartType/lineChart//themeKy/18/groupKy/97/savFile/187, accessed 9 February 2018).

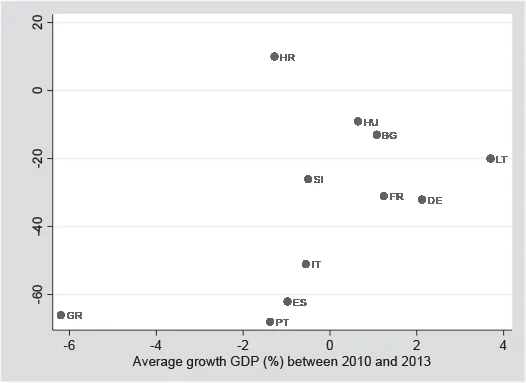

Figure 1.2 Evolution of the levels of trust in the EU among citizens (vertical axis) during the crisis (countries studied by the ENEC project).

Source: Eurobarometer (trust in EU) and Eurostat (GDP growth).

Note

Net trust is the result of subtracting the percentage of those individuals who responded that they ‘tend not to trust’ the EU to those who ‘tended to trust’. Country labels correspond to the official ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 country codes.

These were the main goals we had in mind when we launched the project European National Elites and the Crisis (ENEC) in 2013 that constitutes the basis of this book. In the following chapters we aim to offer a complete image of how the crisis has affected national political elites’ positions with respect to the EU in eleven member states, including some of the most affected ones by the economic downturn (Greece, Portugal, Spain), key member states such as Germany, France or Italy and five Central-Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania and Slovenia). Although the fieldwork of the survey was carried out between 2014 and the beginning of 2015 and, therefore, the opinions gathered were not affected by subsequent important events such as the refugee crisis and Brexit, the analyses that are presented reflect the impact that 4 years of enduring crisis had on the traditional consensus of national political elites on EU issues. More specifically, the following chapters will show to what extent the crisis altered national political elites’ levels of identification with the EU as a supranational entity, their perception of the current functioning of EU institutions, their preferences concerning the advancing of supranational governance and their views about the future of the EU.

In sum, our analyses of the views of national political elites provide important clues about what we could expect about the evolution of the EU and of the European integration project in the next future. In case national political elites (or a significant part of it) respond to citizens’ discontent by adopting more critical positions before the EU, this would certainly jeopardize any advancement in European integration in the years to come. This applies particularly if an increase in Eurosceptic stances takes place in the key EU member states, such as Germany or France. In contrast, resilience of pro-European positions among national political elites would point to a significant disconnection between citizens and their representatives, at least in some countries. This situation represents a double-edge sword for European integration. On the bright side, national political elites’ views could act as a reservoir of political legitimacy for the EU that, once the hardest consequences of the crisis are over, could revitalize citizens’ support for European integration. On the negative side, the gulf between political elites and citizens could reinforce popular feelings of detachment and those Eurosceptical arguments that represent the EU as a manifestation of elites’ interests imposed against the interests of the common people.

In the rest of this chapter we set up the context for the following chapters. In the next section, we focus on the antecedents of the ENEC project, reviewing the literature on national elites’ attitudes towards the EU. Then we outline the features of the ENEC project – the theoretical rationale, research questions, design and fieldwork information. Finally, we introduce the structure of the book, summarizing the content of the different chapters.

National political elites and the European Union

In contrast with the abundant literature on public opinion support for the EU (Loveless and Rohrschneider 2008; Hobolt and de Vries 2016), research on the attitudes of domestic elites towards the EU has been much sparser. Possible reasons are the greater difficulty to access the necessary data, and – particularly until the 1990s – the dominant view among theories of European integration (either functionalist or intergovernmentalist) about the role played by national elites in this process. For these theories, national elites (especially governmental elites) acted both as drivers of the process and intermediaries before national citizens, responsible for legitimating it and granting consensual support for European integration (Haller 2008). In the 1990s, as supranational integration went deeper, this ‘permissive consensus’ paradigm gave way to a new context where EU issues were regarded as increasingly integrated into national political agendas and thus also as more contentious (Hooghe and Marks 1999). The attitudes of domestic elites towards European integration therefore attracted an increasing amount of attention, particularly regarding their twofold role as cueing agents before the general public as well as for their influence in the formation of national political positions (particularly in the case of political elites integrated within parties).

In this respect, most studies have focused on the general support for EU integration among national political elites.4 The first analyses date back to the European Elite Panel Survey (TEEPS) in 1955, 1956 and 1959 (Lerner and Gorden 1969; cited also in Wessels 1995, 141) where elites in France, Germany and United Kingdom were asked if they supported transferring national sovereignty to a supranational institution. In 1959, 2 years after the Treaty of Rome was signed, 74 per cent of elites in West Germany and 68 per cent in France were favourable to such perspective. In contrast, in the United Kingdom, only 48 per cent thought so (Lerner and Gorden 1969, 198). In 1974, another survey (Free 1976, cited in Wessels 1995, 141) found that the proportion of elite members in the same countries in favour of ‘joining a political federation’ were, respectively, 71, 59 and 32 per cent (ibid.). In West Germany, the percentage was even larger 1 year later (79 per cent) (ibid.).

In 1979 the first candidate survey was carried out in the context of the European Election Study, covering the then nine member states.5 The results of this survey showed that political elites were largely in favour of communitarization of important issue areas, mostly those related to transnational issues such as environment, energy or regulation of multinational companies and also agriculture; the same elites were more reluctant with respect to the constitutive functions of the nation-state, such as defence or foreign policy (Rabier et al. 1980; Rabier and Inglehart 1981). Besides, this survey also revealed important differences in the positions of national political elites across countries, with Belgian, German and Italian...