![]()

Chapter 1

The international context of behavioural palliative and end-of-life care

Biopsychosocial and lifespan perspectives

Rebecca S. Allen, Brian D. Carpenter, and Morgan K. Eichorst

Palliative care is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as meeting the physical, psychosocial, and religious/spiritual needs of patients with life-limiting, terminal, or advanced chronic or progressive illness, as well as the needs of their families and caregivers, through an interprofessional team (World Health Organization, 2002). Although the WHO definition clearly delineates psychosocial needs as squarely within the purview of palliative care, certain professions and their treatment approaches (e.g., psychology) have been largely absent in most palliative care settings (Haley, Larson, Kasl-Godley, Neimeyer, & Kwilosz, 2003; Kasl-Godley, King, & Quill, 2014). Similarly, the 2014 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on Dying in America defined palliative care as “relief from pain and other symptoms, that supports quality of life, and that supports patients with serious advanced illness and their families”. The IOM definition does not specifically mention psychosocial needs and largely omits reference to the potential role of psychologists. The emphasis on supporting quality of life among patients and families, however, focuses greater attention on behavioural health issues and needs that may be addressed by psychologists and other behavioural health professionals (e.g., social workers) within the palliative care setting.

The question may be asked, “What is meant by psychosocial needs or behavioral health issues?” Recent systematic reviews (Candy, Jones, Drake, Leurent, & King, 2009; Keall, Clayton, & Butow, 2014; Singer et al., 2016) identify critical gaps in evidence and practice pertaining to behavioural health strategies that may be used to address psychosocial issues within palliative and end-of-life care, including: 1) the need for greater understanding of the role of palliative care among the public and professionals; 2) the need for focus on underserved and under-resourced, potentially high-risk populations; 3) improved communication between patients and family care providers regarding values and treatment preferences; and 4) the value of home services provided either in person or via telemedicine and telehealth. Therefore, behavioural mental health and wellness interventions within the context of palliative and end-of-life care may be defined as directly addressing psychosocial issues that arise and may reflect conflicts of cognition, emotion, and communication both within the individual and within the interpersonal and environmental care context.

This chapter reviews the history of hospice and the palliative care movement and describes theoretical models relevant to behavioural intervention delivery. We describe complexities of conducting intervention research with individuals and families near the end of life. Given the international perspective of this book, we emphasize diversity and intersectionality among individuals and families across practice settings and the course of palliative and end-of-life care. Finally, this introductory chapter ends with an overview of content within this book.

History of the hospice and the palliative care movement

The hospice movement is based on a holistic view of human nature and the fundamental idea that not only physical but also psychological, social, spiritual, and existential suffering may impede a satisfactory quality of life for the dying individual and his/her family. The modern hospice concept was developed by Cicely Saunders, who worked as a social worker, nurse, and, later, a physician in the United Kingdom. Early in her career as a nurse and social worker, Saunders identified several areas for improvement of the treatment of dying patients, such as telling patients about the terminality of their condition; better pain relief; attention to spiritual, emotional, and social needs; and the right to die peacefully (Clark, 1998, 1999). In 1963, prior to the establishment of the first hospice, Saunders traveled to the United States to discuss her ideas about hospice care and soon encountered Florence Wald, who was then the Dean of the Yale School of Nursing (Siebold, 1992). Wald later aided in the founding of the first United States hospice. Around this same time in the U.S., the psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published her book On Death and Dying (1969), with interviews of dying patients. This book had international influence and helped to shape people’s attitudes about transitions to death (Milicevic, 2002). Saunders, Kübler-Ross, and Wald contributed to the development of the modern hospice movement in the United States, Canada, and Europe. The hospice movement spread apace in Westernized cultures (e.g., Australia) but then lagged behind in other countries and cultures (e.g., Asia, Africa).

During the 21st century, the term palliative care has emerged as a distinct, complementary model of care in comparison with hospice (Kelly & Morrison, 2015). Palliative care encompasses all phases of advanced chronic illness and may be initiated at the time of diagnosis and provided concurrently with other disease-related or curative treatments. In many countries worldwide, the palliative care movement has experienced exponential growth. A barrier to systematic and high-quality provision of palliative care remains a lack of understanding by providers as well as the general public about what this treatment model involves. Currently, many providers consider palliative care synonymous with hospice, and community-dwelling adults are unfamiliar with the term.

Unfortunately, direct attention to mental and behavioural health within palliative and hospice care systems has lagged behind its recognition and alleviation of physical, and perhaps even spiritual, symptoms. This seems to be true despite the holistic nature of palliative care, and despite the pervasive psychosocial needs of individuals and families near the end of life. Reasons for this include misperceptions of the potential role of disciplines such as psychology, challenges in reimbursement of all team members, and the nonconcurrent timing regarding delineation of competencies within each profession (Haley et al., 2003). For example, psychology has lagged behind medicine, nursing, and social work in establishing educational curricula and clinical competencies necessary for work in palliative and end-of-life care. In order to address the lack of clinical competencies for psychologists, Kasl-Godley and colleagues (Kasl-Godley et al., 2014) describe the work of psychologists practicing in primary care settings wherein palliative care may be provided. These authors provide case illustration to enrich their discussion of needed competencies for work in palliative care. These competencies include but are not limited to knowledge of: 1) the biological aspects of illness and the dying process, 2) normal versus abnormal grief and bereavement, 3) communication and advance care planning, 4) assessment, 5) intervention, 6) family treatment, and 7) work in multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary treatment teams. These competencies are, of course, shared by other behavioural and mental health professionals. However, psychologists also may bring unique theoretical knowledge, expertise in program evaluation, and other research skills into intervention design and delivery across wide ranging disease and treatment contexts. Foundational knowledge in the biopsychosocial model, as well as developmental and stress and coping theories, may guide treatment and facilitate the functioning of and communication within interprofessional teams.

The biopsychosocial-spiritual model

In his 2002 article using methods of philosophical anthropology to describe a biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care at the end of life, Sulmasy stated:

Having cracked the genetic code has not led us to understand who human beings are, what suffering and death mean, what may stand as a source of hope, what we mean by death with dignity, or what we may learn from dying persons.

(p. 25)

The cornerstone of this model is the premise that individuals are innately spiritual, as many individuals search for transcendent meaning, perhaps particularly near the end of life. Sulmasy elaborates upon Engel’s (1977) original biopsychosocial model by adding spirituality and explaining the importance of additional propositions. First, Sulmasy posits that all individuals exist as beings in relationship; sickness therefore is a disruption of right relationships within and outside of the individual. These relationships exist in interpersonal, social, and transcendent contexts. Second, Sulmasy suggests that healing involves the whole person and restores that which may be restored even when this does not restore perfect wholeness or health. Sulmasy proposes assessing four domains as necessary in the measurement of healing, including religiosity, spiritual/religious coping, spiritual well-being, and spiritual need. The logic of this expanded model fits well in the consideration of psychosocial and behavioural interventions within the context of palliative and end-of-life care. During this period of life, mental health and wellness frequently entail grappling with existential distress, sadness, anxiety, or depression within oneself or within one’s interpersonal and spiritual relationships. Hence, in addition to addressing biological needs for the relief of suffering in palliative and end-of-life care, psychosocial and spiritual needs require direct attention and possible intervention for healing.

As suggested by Sulmasy’s expansion of the biopsychosocial model, many interventions targeting behavioural and mental health and wellness near the end of life incorporate elements of meaning-seeking or spirituality into their treatment approach. Knowledge of such interventions is a core competency for behavioural health specialists in palliative and end-of-life care (Kasl-Godley et al., 2014). For example, in this volume, the chapter by Masterson, Rosenfeld, and Breitbart (Chapter 4) describes Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Cancer Patients and references Victor Frankl’s Logotherapy and the search for meaning (Frankl, 1955/1986; 1969/1988) as seminal to their treatment approach. Additionally, the chapter by Annable, Chochinov, and colleagues on Dignity Therapy (Chapter 5) describes the importance of dignity within the experience of palliative care and approaching death, both for individuals and for their interpersonal support systems. These and other palliative care interventions to address behavioural and mental health and wellness near the end of life incorporate principles of lifespan developmental or stress and coping theories into treatment planning and therapeutic goals.

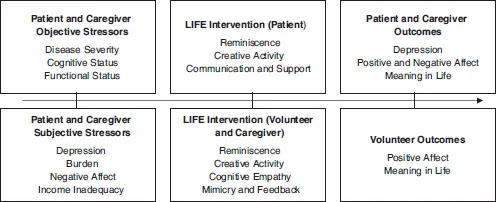

Lifespan and stress and coping theories

Our own intervention work with community-dwelling palliative care dyads (Allen, Hilgeman, Ege, Shuster, & Burgio, 2008; Allen, 2009; Allen et al., 2014, 2016) applies socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Fung, & Charles, 2003; Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999) and the strength and vulnerability integration model (Charles, 2010) to conceptualize why individuals and self-defined family systems are motivated to engage in meaning-making in the service of emotion regulation near the end of life. These theories posit that a foreshortened perspective on time left to live shifts an individual’s motivation toward regulating emotions and engaging in meaningful activities. Stress and coping theories also have considered the importance of meaning-making and suggested how these activities sustain the coping process. For example, Folkman’s (1997) revised stress and coping model expands early theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and describes how the coping process is maintained in the face of unresolved or unresolvable outcomes that may initially be addressed through problem-focused coping strategies. Folkman posits that meaning-based coping consists of revising goals, engaging in positive events, and considering religious and spiritual beliefs. Thus, our intervention approach, like others (e.g., Chapters 4 and 5) uses reminiscence and engagement in dyadic creative activity or legacy making as a therapeutic tool (Allen et al., 2014) (see Figure 1.1.). Through focusing individuals’ attention on lifetime accomplishments and challenges, relationships, and values, behavioural interventions containing these elements facilitate meaning reconstruction and reduce existential distress. Clearly, individuals of different ages or developmental “stages” may approach the end of their lives with differing levels of acceptance and proclivities for positive or negative emotional reactions. Practitioners must approach this work with a sense of curiosity and humility, respecting individual variability embedded within cultural contexts.

Figure 1.1 LIFE Intervention model

Global and cultural diversity and intersectionality in palliative and end-of-life care

Although our prior work has incorporated non-Hispanic White and African American palliative care patients and a self-defined family member from both urban and rural communities in the southeastern United States, many behavioural interventions, including our own, have not adequately addressed issues of diversity and intersectionality (see Chapter 6). With regard to race and ethnicity, it is well known that individuals of varying cultures approach palliative and end-of-life care from different perspectives, emphasizing different values (Kwak & Haley, 2005). With regard to geographic diversity, culture in rural areas is more conservative than in urban ones, valuing self-reliance and religiosity while potentially maintaining a distrust of the medical community (Bushy, 2000). This is particularly true in the southeastern United States, stemming in part from the egregious suffering resulting from 40 years of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, during which rural African American men were denied a known effective treatment for syphilis in order to examine the long-term effects of untreated disease (Ball, Lawson, & Alim, 2013). Likewise, there is likely wide variability in different regions of the world regarding the experience of serious illness and, therefore, what might make for effective psychosocial care at the end of life. Globally, more research is needed to explore the translation of current interventions into culturally appropriate delivery models and settings.

In considering diversity, it is notable that very little information exists with regard to palliative and end-of-life care needs of individuals self-identifying as members of the LGBTQ community, an issue addressed in Chapter 6 of this volume. Another recent book (Acquaviva, 2017) covers communication, attitudes and access to care, shared decision-making and family dynamics, care planning and coordination, ethical and legal issues, psychosocial and spiritual issues, and ways to facilitate institutional inclusiveness for individuals who self-identify within this group and their allies. In certain countries internationally, self-identifying within the LGBTQ community still caries significant personal safety risk directly relevant to biopsychosocial-spiritual palliative and end-of-life care.

The intersection of ethnicity, gender identity, socioeconomic status, and geographic place of residence may expose individuals with greater combinations of low social status identities to significantly more stigma and discrimination. Ghavami, Katsiaficas, and Rogers (2016) describe the need for developmental theories and methods that account for intersectional identities and that examine their relation to lifespan outcomes across life domains. These authors clearly and cogently argue that a focus on only one social status or domain of identity hinders the development and delivery of culturally appropriate and clinically effective behavioural and psychosocial interventions across the lifespan. In this volume, the editors and authors have attempted to include consideration of cultural diversity and ethical care delivery in every chapter, with particular attention given to intersectionality of identities across the adult lifespan.

In palliative and end-of-life behavioural and psychosocial care, fostering a sense of intersectionality and positive marginality (Mayo, 1982; Unger, 2000) may be therapeutically effective in healing. Positive marginality exists when the ...