![]()

PART I

![]()

1Sustaining freshwater security and community wealth

Diversity and change in the pre-Columbian Maya lowlands

Christian Isendahl, Lisa J. Lucero and Scott Heckbert

The archaeology of freshwater security

The centrality of freshwater in our lives cannot be overestimated. Water has been a major factor in the rise and fall of civilizations. It has been a source of tensions and fierce competition between nations that could become worse if present trends continue. Lack of access to water for meeting basic needs such as health, hygiene and food security undermines development and inflicts enormous hardship on more than a billion members of the human family. And its quality reveals everything, right or wrong, that we do in safeguarding the global environment.

(Annan, 2003: xix)

Freshwater security is a global challenge that requires foresight in planning and begs learning from past experiences. Freshwater security is minimally the situation wherein people have access to water of sufficient quality and quantity to meet their physiological needs, including drinking water, water for food production and processing and water for sanitation (Barthel and Isendahl, 2013: 224; see also FAO, 1996). This definition centres on the basic necessities of individuals and leaves out a host of other ecosystem services provided by the hydrological cycle (see also Bakker, 2002; Orlove and Caton, 2010). Factoring these in further emphasises the point that whatever the size, however organised and no matter which biome is inhabited, all societies past, present and future, had or have to deal with freshwater security (see also Wutich and Brewis, 2014). Although global freshwater use is currently within the boundaries of a safe-operating space for humanity (Rockströ m et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015), the uncertainty and lack of adequate freshwater provisioning is regionally acute (Sadoff et al., 2015). Over the past century the total volume of freshwater consumption has expanded rapidly and socially asymmetrically (e.g. McNeill, 2000: 120–122), pushing towards a global post-peak-freshwater situation with decreasing volumes of clean freshwater available to an increasing number of people, and coming at a higher cost. Even without considering the shifting boundary conditions of hydrological cycles that climate change implies, freshwater security forms a daunting global challenge (e.g. Gleick, 2014). Indeed, failing to address this challenge is, as former secretary general to the United Nations Kofi Annan (2003: xix) indicates, an unacceptable humanitarian failure.

Archaeology certainly cannot solve these issues. But since its research generates perspectives, interpretive frameworks and empirical data on the past that no other discipline does, archaeologists can provide endemic insights on freshwater security that provide some leads for the gargantuan task of building sustainable freshwater security at multiple scales. Archaeologists, however, are rarely consulted on key sustainability issues to which they can potentially contribute. Consider, for instance, that of a total of 468 scientific contributors to the most recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2014) 202 (43%) were from the social sciences and humanities. Of these, 130 (64%) were economists. One contributor was a historian, but no archaeologist was involved (Poul Holm, personal communication, 2016). Thus, no contributor elucidated the long-term dynamics of socioecological systems from archaeology’s anthropocentric perspective. This suggests that archaeologists need to find platforms where their voice is heard in prolific scientific-based sustainability fora and that we are well advised to channel our insights to disciplines that decision-makers consult. From the IPCC example, striking a good rapport with Earth scientists and economists does seem particularly productive. Hence, recently the American Anthropological Association Climate Change Task Force published a report that brings to the forefront how people, communities and societies respond and have responded to climate change (Fiske et al., 2015) – topics largely lacking in IPCC (2014) and similar international reports.

The basic scope of the archaeology of freshwater security is twofold. First, it generates case studies of the opportunities and challenges that people in the past have addressed to attain freshwater security, and their successes or failures to do so. Second, it employs archaeology’s unique anthropocentric perspective to study the long-term, socioecological dynamics framing freshwater security under different and changing conditions, usually focusing on the Holocene to Anthropocene period of the last c. 11,500 years.

But there are caveats. As Lane (2015) notes, what is considered as long-term differs between the disciplines and is dependent on the kind and relative scale of the longevity of the processes analysed. Hence, ‘the long-term’ needs always to be specified rather than implied. The temporal frame of reference within which the archaeological analyses of freshwater security operate usually extends from a few hundred years to two or three millennia, i.e. over the longue duré e in the popular parole of the French Annales school of historians (Braudel, 1980). However, there is no standard frame of reference. This has important consequences for how we construct, evaluate and ultimately project the sustainability of social institutions addressing freshwater security. Although not unproblematic, the archaeological perspective is unique in terms of being able to track the effects of relatively slowly changing variables (Carpenter et al., 2001), i.e. processes with long-term temporal lags that otherwise might go unnoticed, such as the gradual long-term effects of a maximising productive strategy on the sustainability of an agricultural economy’s resource base. As an anthropocentric science, archaeology is concerned with what people have done, why they did so, and determining the outcome of these actions, both short- and long-term. That human practice involves both calculated and unrealised tradeoffs playing out over different temporal and spatial scales and social domains to undermine socioecological resilience have been recognised in the sustainability sciences for some time (e.g. Janssen and Anderies, 2007). For instance, Nelson and colleagues’ (2010) comparative study of pre-Columbian agricultural systems of the North American southwest demonstrates the so-called robustness–vulnerability tradeoffs at work in managing freshwater security and offers insights on the relatively high resilience capacity of flexible small-scale technological solutions (see also Hegmon, 2017). Although the archaeological record cannot provide blueprints for implementing freshwater security because of our living in a globalised world with exponentially greater numbers of people, it does offer a pool of experience of challenges, strategies, practices, successes and failures from which to draw.

Today the tropics host over 40% of the world’s population (a proportion expected to expand to 50% by 2050) (State of the Tropics, 2014: xii), with nearly half estimated to be susceptible to water stress (State of the Tropics, 2014: 55). It is, thus, critical and timely to discuss freshwater security in the tropics with an ultimate goal of addressing present concerns. This chapter discusses freshwater security among the pre-Columbian Maya in tropical Central America. We offer some examples of how the Maya developed water management systems in different regions and how efficient these were in providing freshwater security sustainably (see also Tainter et al., this volume). In this and other tropical regions worldwide, unless freshwater security is maintained, not only will shortages worsen, but water-borne diseases will proliferate. People will suffer.

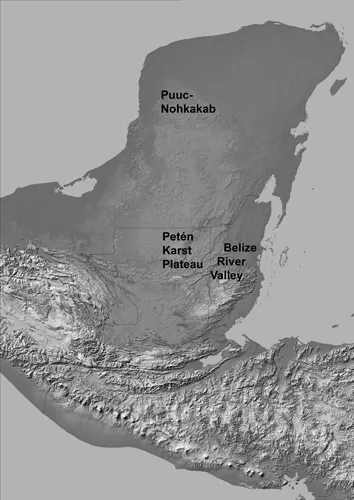

The Maya lowlands are environmentally heterogeneous and different regions presented challenges as well as opportunities within certain socio-political, cultural, historical and environmental constraints to address freshwater security. For instance, the Maya had no beasts-of-burden or wheel-based transport and several regions lacked water-borne transport routes. Since people often had to carry goods, distant production of bulk food was relatively inefficient and contributed to an emphasis on urban farming in the total food resource framework (Isendahl, 2012; Barthel and Isendahl, 2013; Isendahl and Smith, 2013). In response to this diversity, a variety of water management systems were developed in different social and historical contexts (Lucero, 2006; Isendahl et al., 2016; see also Dunning and Beach, 2010). In this chapter, we initially focus on two regional examples of how the Maya addressed freshwater security: the Puuc-Nohkakab region in the northern Maya lowlands of the Yucatá n Peninsula and the Peté n Karst Plateau of the southern Maya lowland interior (Figure 1.1). As we will see, although these regions are located in different areas with different cultural histories and environments, there are significant similarities in the general pattern of how freshwater security was addressed and the consequences of these water management systems for long-term societal sustainability. We then present a third, contrasting case study based on the site Saturday Creek in the Belize River Valley, immediately to the east of the Peté n Karst Plateau. Saturday Creek brings in considerable dissonance to the first two cases presented on how pre-Columbian Maya water management systems performed in addressing freshwater security long-term.

Figure 1.1 The Maya region with the physiographic sub-regions discussed in the text indicated (plotted by C. Isendahl on a modified map from NASA, www2.jpl.nasa.gov/srtm/central_america.html; accessed 22 November 2011)

Theoretical baseline

As an initial point of departure for purposes of our discussion, we provisionally suggest that long-term freshwater security is equivalent to a sustainable water management system and can largely be understood as a result of successful problem-solving. A water management system is here broadly defined as the sequence of activities that link water ‘production, processing, distribution, consumption and waste management, as well as all the associated regulatory institutions and activities’ (Pothukuchi and Kaufman, 2000: 113). Tainter and colleagues (Tainter, 2006; Tainter and Taylor, 2014; Tainter and Allen, 2015) argue that sustainability emerges from success at solving problems, and that technological and institutional complexity – defined as ‘differentiation in both structure and behavior, and/or degree of organisation or constraint’ (Tainter, 2006: 92) – is not only a powerful tool for problem-solving, but also that complexity requires resources and involves costs to be maintained.

Complex water management systems depending on management-intensive hydro-technological solutions, for instance, those dependent on investments in a system of reservoirs, distribution canals and other large-scale landesque capital features (i.e. landscape transformations made to increase productivity), carry relatively high costs. Although the solutions applied to build freshwater security by increasing technological sophistication and involving complex forms of management organisation may be highly effective for a time, they require resources such as up-front investment and ongoing maintenance costs, which carry with them a long-term series of inbuilt costs that can limit the future capacity to adapt (Scarborough and Burnside, 2010). Maladaptation and responsive inertia (i.e. too little too late) may be associated with sunk-cost effects, i.e. that decisions are based on past investments rath...