1 An Introduction to an Interpretation of Equal Protection of the Laws and Integration in Terms of Belonging

Introduction

The argument of this chapter is that both “the right to equal protection of the laws” and the idea of integration can be understood in terms of belonging and that there is a link between the two. The argument starts by suggesting that the general “right to equal protection of the laws” should be understood in terms of belonging. The reader is introduced to the suggestion that the equal protection of the laws means a Right to Equal Belonging in a Democratic Society (section I). It is then explained that integration can be understood in terms of belonging too. It is indicated that integration may also mean an equal belonging in a democratic society (section II).

I. Equal Protection of the Laws in Terms of Belonging

The equal protection of the laws should be understood in terms of belonging. The way one belongs to a group is the way one stands in relation to the other members of the group, in respect of certain goods of reference the group provides to its members. Belonging to a group means membership. The way one belongs to a group is thus the quality of one’s membership. Whether one enjoys equal membership in a group is a matter of whether one equally belongs to this group.

Dred Scott v. Sandford,1 Plessy v. Ferguson2 and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka3 promote two distinct and opposing models of membership in the society. On the one hand, the two former decisions illustrate the model of non-belonging in a community of equals. On the other hand, the latter promotes a model of belonging in a community of equals. This is a community whose members are of equal worth.

Dred Scott was clearly excluded from the larger American society.4 He was among the enslaved African Americans of his time. He spent time in the free states. He sued then for his freedom. The Court, cynically affirming his arbitrary exclusion from the society of equals, held that Dred Scott was not “a person” for the purposes of the Constitution. He was a slave, not a citizen. Therefore, he was not entitled to sue. He could not have standing before the court and his “claim” was procedurally not even a claim. The Court did not have any jurisdiction to decide his “claim.”

Dred Scott did not belong in the larger American society as an equal. He belonged to his master with the rest of his master’s property. He was, according to the Court, “a part of the slave population rather than the free.”5 His claim was nothing else, but a “claim” to have an equal place in the larger society, in its most basic form: to be recognized as free and equal, as he was born,6 and be free from domination of other people. His exclusion was a violation of the most basic form of equality. The violation of his freedom was so deep as to violate the absolute core of all human rights, that is, human dignity and respect. The Court’s decision was thus a regretful declaration that Dred Scot did not belong in the society in its most basic form; that is the equal belonging to the universal family of human beings.

Then in 1890, the Separate Car Act from the state of Louisiana was passed. The Act required separate accommodations for blacks and whites on railroads, including separate railway cars. In 1892, Mr. Homer Plessy refused to obey. He instead sat in “the whites-only” railway car. He was asked to sit in the “correct” car, “the blacks-only” one. He refused, he was arrested, and he was remanded for trial. In 1896, his case finally reached the Supreme Court of the United States, challenging the law of Louisiana as a violation of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution of the United States.

Mr. Homer Plessy was asking for something more than merely the freedom to choose his seat in the railway car. He was asking for an equal place in the larger society. He did not want to live in a separate segment of the society that was forcibly chosen and constructed for him. He was challenging his arbitrarily inferior membership in the society. He was claiming to belong to the larger American society as a member of a community of equals. A minimum sign of this equal belonging would be his choice for any available seat in the railway car. However, the Court held that “separate but equal” was constitutional.

The Court overturned Plessy in 1954. The Warren Court7 concluded that the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place in the field of public education. It clearly declared that “[s]eparate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws.8 For the Supreme Court of the United States in Brown, the main question was whether segregation deprives the black children of equal educational opportunities. The Court explained:

[t]o separate them [the Negro children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.9

Thus, the Court talks about a feeling of inferiority as to the status of the African American children in the community which causes a particular harm. Let’s analyze the above statement word by word. First, in the Court’s understanding, it is a feeling which is at stake. Feelings exist in a relationship. Second, it was about a feeling of inferiority. It was about a feeling of the black children that white children are superior to them. Third, the Court talks about the feeling of inferiority regarding the status of the children. In other words, the Court connects the feeling of inferiority to the place these children feel that they have in the society. Fourth, the Court found that such is the harm caused by the feeling of inferiority that it may affect the hearts and minds of the children in an irreversible way. One could only rhetorically ask what kind of harm could be more serious than an irreversible harm caused in the heart and mind of a child? The feeling of inferiority of the black children as to their status in the society, which the Warren Court referred to, can be paraphrased in terms of belonging. The above wording of the Warren Court is just a different way of describing the black children’s feeling of being inferior members of the society.10 In other words, the community of equals is understood based on children’s feeling of having or not having equal belonging.

The Warren Court quoted the Supreme Court in Kansas in its factual finding on the connection between this feeling of inferiority caused to the black children and their motivation to learn. The opinion of the Supreme Court of Kansas cited social science developments which their factual findings confirmed. In particular, the Kansas Court had found that this feeling of inferiority influences in a negative way the motivation of the children to learn. It had also pointed out that the impact is greater when it has the sanction of law, as such policy denotes the sense of inferiority. The Court then concluded that segregation with the sanction of law has a tendency to delay the educational and mental development of black children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would otherwise receive in a racially integrated system.11 Thus, the Kansas Court talked about the nature of the specific harm that segregation causes to black children, connecting the feeling of inferiority caused to them to a worsening in their motivation to learn.

Reflecting on “the right to equal protection of the laws” in education between a black and a white child under the facts of Brown, one can see a triangular relationship. It is a relationship between the State, which provides the education, and these two children. Let’s say that the good of education is the good of reference in this example. Under conditions of equality, the relationship of each of the two children with the State, should be equal in respect of the good of reference and then in comparison and in relation to each child. But the quality of relationships is determined by some general parameters like distance/proximity, communication/lack of/weak communication, trust/distrust, safety/insecurity, care/indifference, comfort/discomfort and fairness/injustice. There are therefore two primary relationships. The one is the relationship between the good of reference, offered by the State, and the black child. Think of this relationship, under conditions of equality, in the following figure:

Figure 1.1 Relationship A

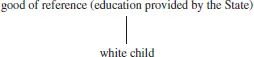

The second primary relationship is the relationship between the same good of reference, offered by the State, and the white child. Think of this relationship in the following figure:

Figure 1.2 Relationship B

Then, we need to compare these two relationships and see if there is inequality between them. Under conditions of equality, the two above relationships seem to be equally close. Trust, freedom, communication, security, comfort are some of the parameters which make the participants in a relationship close. The lack of these parameters will distance the participants of the relationships. In this sense, at least, under conditions of equality, the distance between the children and the good of reference in the above two relationships is equal.

To treat the two children differently by separating them because of their color and providing fewer educational opportunities to the black child, was, according to the Warren Court in Brown, an arbitrary differential treatment and it was discriminatory. We can perhaps think this comparison of the two primary relationships under conditions of inequality in the following figure:

Figure 1.3 Relationship A

Figure 1.4 Relationship B

An unequal relationship with the education provided by the state means an unequal relationship with the good of reference. One can see in the above figures that the distance of the black child to the good of reference is longer than the distance the white child had to the same good. This illustrates inequality in their relationships to the same good of reference. If one tries to put together the above figures of the primary unequal relationships, one will observe a non-isosceles triangle.

Ultimately, unequal relationships of the two children to the certain good of reference of education offered by the State means an unequal belonging to the State. As Chief Justice Warren said, “[t]oday, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments […]. It is the very foundation of good citizenship.”12 Karst finds that Chief Justice Warren was building a nation in Brown.13

Donna Greschner has also understood the purpose of the equality rights under section 15 in terms of belonging. She suggests that equality rights ensure belonging to three main communities: to the universal co...