![]()

Part I

Copying and modelling

Introduction

Models are made in multifarious media and of multifarious materials, they represent a most astonishing number of objects and they are used to accomplish a host of different tasks. We encounter them as mathematical models and car models, mannequins and model houses, role models and digital models. They appear in everyday settings, in politics, the sciences and the arts. In short, they appear in so many versions, formats, materials and settings that the word ‘model’ seems to refer to phenomena that have nothing in common but the term.

There are many models in collections and in museum exhibitions. But what are models in a museum? What do they represent? How are they presented, categorised and conserved, and for what are they used? Answers to these questions are many and vary over time and across museum types; as the following chapters make clear, museum models are worth studying because they help us interrogate and understand how museums work, how collections are established, how objects are documented and conserved and how exhibitions and didactic activities work with objects. They also help us to answer a central question in this book: How and to what degree are copies and copying practices at the heart of museum practice?

The first of the four chapters in Part I uses the term ‘copy’ as an analytical lens to compare a set of objects that also can be termed ‘models’, ‘replicas’ or ‘reproductions’. A team of scholars working in different departments in the National Museums Scotland present these different objects with the aim of describing the value of copies in museums and the work they do. They focus on specific phenomena and the materials used. The objects are chosen from different collections and museum departments: A miniature engineering machine, a papier mâché larynx, a set of pear wood crystallography models and a pair of illicit reproductions of early medieval silver objects. The authors’ choice of comparing these objects across materials, disciplines, departments and sites brings the role of presentation and imitation in museums to an eye-level view. Through labelling the objects ‘copies’, the authors foreground the many areas of museum work implicated in imitation work. Focusing on materials and size also points to the performative nature of copies. Copies model museum disciplines and didactics, exhibition and conservation work.

In the second chapter, ‘model’ is the lens through which collecting and collections in an eighteenth-century scientific society are seen. What made a model a model? How was ‘model’ understood and used in the learned environment of the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters in Trondheim, one of the larger Norwegian cities at the time? The chapter deals with how models, in different ways, moved into – and out of – collections. It also describes differences in function: A model could be a description or a prescription, a blueprint or a proof. What might be surprising is how ‘model’ in many ways carried the same connotations as today. Yet, eighteenth-century models that were part of knowledge-producing activities were never structural or abstract. They were typically wood-carved instruments for transporting and attaining new knowledge in different forms. Today there are few traces of these models, and we can infer that they, in the Trondheim collections, have suffered the fate of so many other copies in collections: At some time, they disappeared from the interest field of the learned, including the collection curators, and thus become interesting only when rediscovered as historical sources.

The third chapter in this part brings us to a type of museum where copies have thrived: Museums of science and technology. The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology started to collect and document industrial heritage in the 1940s. The chapter follows the different routes of heritage work in the museum – documenting, modelling and recreating – and uses two flour-grinding mills as examples. The reason for copying in these two examples and the understanding of what was copied – the techniques, purpose and use of the copies – was noticeably different at different times and in the visions of the various actors and groups of people involved. The two cases also demonstrate diverging concepts of technology, time and history. Copying might serve to preserve historical remnants, to separate something from time or space or to re-enact or recapture a specific historical period.

The last chapter discusses modelling as concept and practice within the field of natural history. Whereas ‘models’ in the seventeenth century referred to three-dimensional models, modelling in the form of conceptual models and abstractions became central in scientific practice in the nineteenth century. However, physical specimens still play a decisive role in natural history museums. The chapter analyses specimens in relation to the categories they are supposed to represent. More specifically, it interrogates the role of type specimens as ‘models of’ and ‘models for’. The author takes us beyond any simple notion of copying. Copying is at the heart of the natural world: Reproduction is a core function of organic nature. A museum of natural history is thus not just a storehouse for specific originals, but a vast reservoir of museum specimens that can be used for different purposes, for example, for modelling effects of environmental changes. The chapter shows the crafting of natural specimens as originals, replicas and representatives.

Models and other copies thus are at the core of museum practices. Models play a central role in collecting and exhibiting and in other museum activities. And as the four chapters in Part I clearly show, they are particularly important as knowledge production and disseminating tools.

![]()

1 The art and science of replication

Copies and copying in the multi-disciplinary museum

Samuel J.M.M. Alberti, Alice Blackwell, Peter Davidson, Martin Goldberg and Geoffrey N. Swinney

It is ironic that although the credibility of collections is often bound up in the authenticity of artefacts and specimens, museums nonetheless hold many imitations and models. From exquisite glass flowers to miniature ships, copies have held key places in museums since their inception and serve many functions. These fascinating objects have attracted considerable scholarly attention, and yet too often this is focused on a particular phenomenon or material. Here we want to cut across disciplinary boundaries to juxtapose a selection of models to understand the differential value of copies in museums and the work they do.

This article will interrogate the copy as a museological phenomenon via four (sets of) objects, spanning archaeology, medicine, science and technology. Our first is one of the National Museums Scotland’s renowned engineering models, with its hallmark motion. Second is a strange, otherworldly papier-mâché larynx from the renowned nineteenth-century Auzoux factory. Like the larynx, the purpose of our third case study – early nineteenth-century pear wood crystallography models – was ostensibly educational. These were precisely rendered, crafted to illustrate a pioneering textbook. In contrast, our final objects’ precision was motivated by deceit: A pair of illicit reproductions fashioned after early medieval silver objects discovered at a mound known as Norrie’s Law in 1819.

These objects are selected to emphasise the ubiquity of imitation across the arts and the sciences. We seek to expose the differences and similarities in the function of copies and, in particular, what their respective materials and scale afford. Our aim overall is to ask, how are copies used and valued in museums?

What these have in common is their location within the holdings of what is now National Museums Scotland. This institution has a complex pedigree involving the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, established in 1780; the University of Edinburgh’s collections, which were set on a firm footing in the early nineteenth century; and the Industrial Museum of Scotland, founded in 1854 (Swinney 2013). The latter two collections were housed within the institution which by 1904 had become known as the Royal Scottish Museum; this then amalgamated with the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland in 1985. Our copies stem from each of these diverse elements, and this chapter takes the opportunity to widen the focus across the Museum’s material spectrum of science, nature, art, culture and (of course) all things Scottish.

Miniature machine

In the nineteenth century and for much of the twentieth, given the limited space in the Museum, the only practical means of fulfilling its objective to represent much of ‘the industry of the world in relation to Scotland’ was in miniature (Wilson 1858, 55). The Museum therefore acquired or constructed numerous engineering models, many of them sectioned to show their anatomy. By the early 1890s the displays of engineering, comprising mostly models, occupied a newly constructed ‘Machinery Hall’.

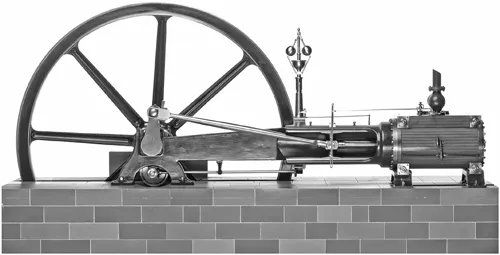

Models were especially important in this area because of the tradition of model-making in the engineering industries. Miniature versions of their products were often generated by firms for use as part of the design process, as apprentice pieces and as illustrations to prospective clients. The Museum acquired many such models from Scottish engineering companies, and from 1868 it began to craft its own. The Museum workshop emulated the processes by which the full-size counterparts had been made, taking great pride in fidelity to original materials and processes. However, this verisimilitude was at best only ever partial – for example, the stone or brickwork supports to machinery were invariably represented in papered wood, as displayed in the 1:6 scale ‘Corliss Engine’ built in 1876 (Figure 1.1). Named for the American engineer George Henry Corliss and featuring innovative valve gear, this type of stationary engine was used in factories and especially in textile mills. The model, with its gleaming steel drive rods, brass fittings and wood-clad steam box, was made to scale from plans supplied by Douglas and Grant, a major manufacturer of this type of engine.

Figure 1.1 Model of a patent Corliss engine, horizontal and non-condensing, scale 2 inches to 1 foot, made from designs by Messrs Douglas and Grant of Kirkcaldy, 1876. 155 cm wide.

Copyright the Trustees of National Museums Scotland.

In the early twentieth century, the Museum workshop introduced a new initiative which involved copying in a different dimension: Movement. Not only would the material form of a machine be represented, but so too could the choreography of its component parts. Thanks to the introduction of electricity, belt-drives from a motor in the base of the display case provided the motive power and a push-button switch enabled the visitor to set the exhibit in motion for a short while. The Corliss engine was thus animated in 1903; over the years the Museum added to the number of push-button activated models and the ‘Machinery Hall’ was renamed the ‘Hall of Power’. The visitors’ ability to set many of the models in motion and to see for themselves the relative movement of components became a mainstay of a policy to introduce ‘a certain amount of realism’ and to make exhibits ‘self-interpreting’ (Martin 1912, 2).

Over the twentieth century, push-button models became for many visitors the defining feature of the Museum, undoubtedly the most heavily used of any of the copies we consider in this chapter. Director Douglas Allan emphasised in the mid-century: ‘models of ships, engines, and coal mines, these are accurately constructed scale copies of large objects, too big for museum display, in which the aim is to show the design, function and purpose’ (Allan 1948). In attempting to copy and display ‘function’, however, much was left out. In miniature, the world of work was sanitised and aestheticised. Lost was the din of the shop-floor or engine-room, the scalding heat of steam, the smoke, soot, dust and grime, the smell of oil, grease, diesel or petrol. The human element was also conspicuously absent: The machines’ operation required no heavy work, no skilled manipulation of controls, no stoking of furnaces. And unlike in their workplace counterparts, the motions of these miniature machines produced no end-product – these representations of manufacturing and propulsive technologies neither manufactured nor propelled (Staubermann and Swinney 2016). The m...