![]()

Part I

Principles and Practices

![]()

1 Classical Music, Copyright, and Collecting Societies

Brian Inglis

Introduction: Copyright and the (Classical Music) Work-Concept1

Copyright and classical music have a symbiotic relationship.2 Although copyright once simply denoted the legal right to copy specific documents, it achieves its fullest potential when it defines fixed, bounded, and original abstract entities manifested in one or more physical modalities. The description readily applies to (implicitly classical) musical works, which Lydia Goehr calls ‘ontological mutants’: a piece’s identity lies neither in its score, for music is an aural medium, nor in any single performance or recording, for the same score gives rise to different interpretations; it is instead abstracted from the sum of all potential realisations.3 These conceptions, then, rely on abstraction but also containment and association with a single individual: musically, the composer. Goehr coined the term ‘work-concept’ to encapsulate her idea, defining musical works as ‘complete and discrete, original and fixed, personally owned units.’4

This theoretical framework is important because it corresponds perfectly with how modern copyright professionals routinely use the term ‘work’ to denote discrete units under copyright protection, be they musical, artistic, or literary. As Anne Barron has observed:

Copyright law not unlike musicology operates with a conception of the musical artefact as a bounded expressive form originating in the compositional efforts of some individual: a fixed, reified work of authorship.5

Friedemann Sallis has identified a ‘weak’ work concept informing music composition before the French Revolution: composer-performers were seen as enacting a craft, and music was about events rather than ideas; process rather than product. This was overtaken by ‘the era of the strong work concept’ from the late 1700s to the present day, in which ‘music conceived as “works” consigned to paper … emerged as a new concept that had a major impact in Western culture.’6 Significantly, the newer concept acquired a regulative role, not only in terms of aesthetic ideology but also by influencing copyright legislation:

In the early eighteenth century, publishing houses acquired copyright … insofar as sheets of music were produced. For most of the eighteenth century copyright remained so defined. In 1793, however, copyright laws were passed in France to transfer ownership away from publishers to composers … [reflecting] the basic idea that composers are the first owners of their works, for it is they who put the works in permanent form [by notating them].7

Goehr and others have traced the rise of this strong work-concept, which spread from France across Europe in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—a period in which the enduring productions of copyright legislation and Viennese musical life also flourished. The pivotal figurehead, of course, was Ludwig van Beethoven, who effectively elevated the musical score from being ‘a more or less detailed map to being a full and complete representation of a work.’8 Similarly, a composition was no longer mere craftsmanship but an autonomous work of transcendent art.9 An emerging Romantic aesthetic accordingly emphasised, and valorised, originality.

This cultural zeitgeist engendered changes in copyright legislation that enhanced abstraction. New laws were enacted to extend protection to performances of musical works (the “performing right”) in Prussia (1837) and the United Kingdom (Thomas Talfourd’s Act of 1842).10 The ideology of Romanticism continues to inform the regulative function of the work-concept: both modernist classical music and the rock concept of “authenticity” inherit elements of it, as qualities such as rebellion, shock, alienation, the transcendent power of the original, and the aspiration to art attest. The incorporation of popular musics into the ambit of the work-concept is particularly interesting—and, as we shall see, relevant to classical music. In nineteenth-century France, such styles were originally excluded from legislation, being considered insufficiently “original” or worthy of artistic or commercial status.11 Because certain popular forms, such as Victorian ballads and Tin Pan Alley standards, divide labour between writer(s) and performers—a mode still evident in modern pop icons reliant on “hit factories” or shows such as The X Factor—they more obviously fit the work-concept template than, say, the group dynamic of later blues-based rock music, where the functions and boundaries of composers, performers, and indeed of the work itself, are more blurred.12

For popular music productions in oral traditions to acquire copyright protection, the tangible trace (in copyright law, the “fixed form”) became the original recording. This required some abstract thinking on the part of lawyers and administrators to conceptualise the “work” underlying and separate from the sounds (a case of strengthening a weak work-concept). In the UK, copying the underlying works in musical recordings (“mechanical copyright”) was first controlled by the 1911 Copyright Act, which led to the establishment of what became the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society (MCPS, allied with the Performing Right Society (PRS) since 1998). Protection of copyright in sound recordings themselves was established by a court case that led to the founding of the “neighbouring rights” (i.e. non-authorial copyright) society Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL) in 1934.

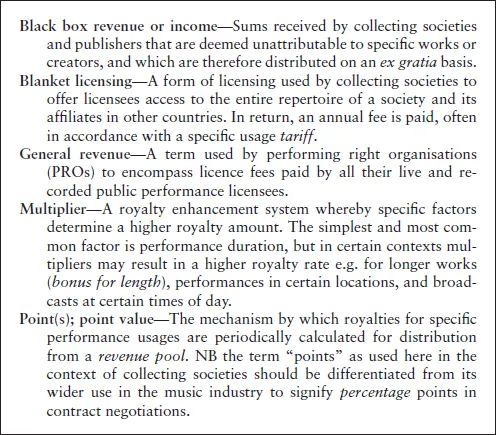

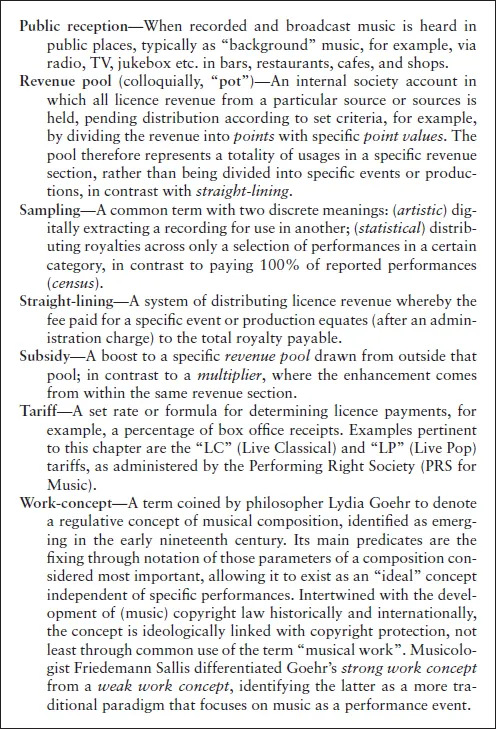

As Ron Moy has argued, the evolution chronicled here has much to do with a general desire to identify popular music-based products with individuals, and the consequent necessity to construct singular authorial subjects.13 More recent popular music forms, such as electronic dance music with its reliance on sampling and remixing, have posed stronger ontological challenges to the work-concept. Such issues will be revisited later in the chapter, which focuses primarily on the copyrights of classical composers.14 It scrutinises how and why the PRS instituted a Classical Music Subsidy and removed it at the end of the twentieth century. The episode illuminates the roles of collecting societies, how the performing right is mediated in practice, and how socio-political shifts reframe copyright societies in general and classical music in particular. Finally, we zoom out to examine contemporary copyright challenges and debates, again nuanced by a classical music perspective. As in academia, the worlds of copyright and collecting societies are replete with acronyms and specialist terminology. Figure 1.1 therefore offers a glossary of some of this chapter’s key terms.

Figure 1.1 Glossary of Specialist Terms Used by Collecting Societies and Musicologists

Collective Licensing: The Performing Right Society (PRS)

To administer copyrights, composers and their publishers rely on collecting societies to license music “users” on their behalf, from live and recorded performance premises and cinemas, to record labels, broadcasters, and, more recently, online entities.15 Also known as authors’ societies, or Performing Right Organisations (PROs) when performing rights are involved, collecting societies are typically national monopolies, linked by reciprocal agreements with affiliated societies across the world. The PRS (“PRS for Music” since 2009) was formed in 1914 with a committee of composers, authors, and publishers.16 Composers were largely drawn from the popular and light music sphere, but classical publishers were well represented, including William Boosey and Charles Volkert (of German publisher Schott, among other publishers). Tracing the society’s history three-quarters of a century later, Cyril Ehrlich argued that

[The PRS], as it approached a seventy-fifth birthday, continued to serve the general public no less than its members. The former were provided with access to the world’s music, easily and cheaply, while giving due reward to its producers … Among the members there was general satisfaction with the Society: an efficient alliance of interests, maintaining a reasonable balance between writers and publishers, [and between] serious and popular music.17

This Panglossian conclusion may not have been entirely inappropriate at the time of the book’s publication, but, a mere decade later, members, management, the Board, and even promoters, would be at loggerheads—a situation that threatened to pull the PRS apart and, according to some, to decimate the composing profession in the UK. Let us now explore the primary catalyst for this explosive reaction.

§

To the Arts Council, it had been an ‘enlightened example of musical patronage.’18 To British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors (BASCA) chief executive Chris Green its removal was ‘the most terrible tragedy.’19 To Terri Anderson (PRS’s then Communications Director), its abolition was part of the ‘slaughtering of a number of sacred cows’ by a ‘determined and unsentimental’ chief executive, John Hutchinson.20 To composer George Benjamin, its disappearance was ‘the worst thing that has happened to classical music in my lifetime.’21 One of many changes PRS made to its distribution policy at the end of the twentieth century, the withdrawal of its subsidy for live classical concert royalties was a high drama of cultural politics, bitter wrangling, unresolved resentments, and long-term relationship disruption. The voluminous textual trace left by the episode allows us to recount the facts of the matter and to examine some of the contexts and ideologies underlying participants’ actions, responses, and debates.

What was the Classical Music Subsidy (CMS)? The origins of the mechanism that had acquired this label by the 1990s are hard to pinpoint, but its contexts are clear. The first is the enormity of the task facing all PROs in identifying all public performances of copyright music by any means within their given territory of jurisdiction; that is, licensing them and acquiring data to inform distributions of this “general” revenue. Recorded public performances—to the smallest shop or bar with a radio, TV, or stereo playing in the background—are arguably the hardest to identify. The impossibility of negotiating separate licenses for every work that might be used leads to “blanket” licensing solutions. In return for access to the repertoire of the licensing society and its international affiliates (that is, virtually all copyrighted music), users are charged according to tariffs for different types of use, creating revenue “pools”. Likewise, the impracticality of having a direct royalty distribution from every licence fee paid to every work performed (sometimes called a “straight line”) means that distributions of general revenue have always depended to an extent on ideological decisions. And while broadcasters are easier to manage in licensing and reporting terms, the issue of how to allocate, or subdivide, into multiple usage subcategories those large blanket licence lump sums paid annually by public broadcasters such as the BBC is inevitably a matter of collecting society policy.

This practical reality leads to a second, more specific context, which Ehrlich outlines:

Methods of redistributing income within the Society had been discussed at least since the 1920s, when there was talk about compensating “serious work” as against “commercial music”. It was also a policy long established by CISAC [Confédération Internationale de Sociétés d’Auteurs et Compositeurs, the umbrella organisation representing ...