eBook - ePub

Early Music Printing in German-Speaking Lands

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Early Music Printing in German-Speaking Lands

About this book

The book draws upon the rich information gathered for the online database Catalogue of early German printed music / Verzeichnis deutscher Musikfrühdrucke (vdm), the first systematic descriptive catalogue of music printed in the German-speaking lands between c. 1470 and 1540, allowing precise conclusions about the material production of these printed musical sources.

Chapters 8 and 9 of this book are freely available as downloadable Open Access PDFs at http://www.taylorfrancis.com under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND) 4.0 license.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Early Music Printing in German-Speaking Lands by Andrea Lindmayr-Brandl, Elisabeth Giselbrecht, Grantley McDonald, Andrea Lindmayr-Brandl,Elisabeth Giselbrecht,Grantley McDonald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Music printing and publishing in the fifteenth century

1

Early music printing and ecclesiastic patronage

Printing was first established in Mainz, the seat of the archbishop who was the most important of the seven Electors of the Holy Roman Empire and head of the largest ecclesiastical province of that Empire, containing 17,000 clerics who made a perfect market for liturgical books.1 The Council of Basel had ended in 1449 with the imperative to distribute newly reformed liturgical texts across Europe, and music was an integral part of those reformed texts. Although it appeared that the entire international church was behind the adoption of the conciliar reformed Liber Ordinarius, the Council of the Province of Mainz that met in 1451 voted against what was essentially a Roman liturgy, supporting instead a text offered by the archbishop of Mainz.2 Despite the pope’s threat to use military force if necessary, the council ended by sending bishops and abbots back to their homes to create unique reformed diocesan and monastic texts in a giant exercise in textual editing.3 The publication of hundreds of editions of liturgical books – tens of thousands of copies – would have to wait.4

Music was in the middle of the struggle over textual orthodoxy. Every priest was required to have a missal, an enormous market for printers, and music was a necessary, if small, part of the genre, the fairly simple plainchant sung by the priest. On the other hand, choirbooks, agendas, services for the dead (vigiliae, obsequiale) contain melismatic chant on nearly every page, requiring complex neumes of music type designers. The crucial significance of choir music in the liturgical reform movement is demonstrated by the fact that music was first printed in choirbooks.5 We know how the struggle for uniformity in liturgical texts ended. The international distribution of new books sought by council reformers and promised by the invention of printing would be the Roman liturgy authorised by the Council of Trent in the next century, but only after northerners had been allowed to see into print their regional texts and chant celebrating local saints and practices.

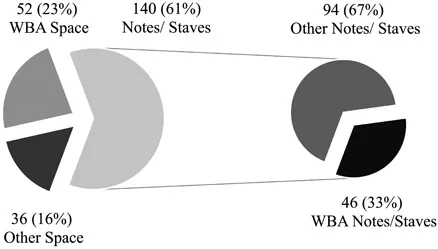

Figure 1.1 The impact of ecclesiastical patronage on incunabula of German lands with printed music or space for music. WBA = Würzburg, Bamberg, Augsburg

Bishops and abbots played a major role in bringing their reformed liturgy to print, investing large sums of money in the creation of impressive text and music types and in the printers able to compose such type. Solid evidence of relationships between ecclesiastical patrons and printers exists for liturgical printing in Würzburg and later Eichstätt with Georg and Michael Reyser, Bamberg with Johan Sensenschmidt, Steffan Arndes in Schleswig and Lübeck, and Augsburg with Erhard Ratdolt. Those printers alone published one-third of all fifteenth-century German liturgical books printed with notes and staves (46 of 140) and well over half of the liturgical books with space for music (52 of 88) (Figure 1.1).

Würzburg: Georg Reyser and Prince-Bishop Rudolf von Scherenberg

The first example of ecclesiastical sponsorship of liturgical printing is a contract for a territorial monopoly of the new technology of printing. The privilege awarded to the first printers in Würzburg by Prince-Bishop Rudolf von Scherenberg, the governing prince of his territory, just east of Mainz, is clearly described in a letter in the first book off the press, the Breviarium Herbipolense (after 20 September, 1479):

The liturgical books of our Würzburg choir should be circumspectly examined, corrected, and improved with the utmost care by selected men whom we considered suitable for this task – which we have indeed found to have been carried out with utmost attentiveness – so, in order that the prelates and other priests and office holders of our city and diocese might in all future times benefit and prosper from this due correction and integral renewal of the books, we have therefore decided that nothing could be more proper and even opportune than that in accordance with the correction and improvement of the liturgical books their impression should be carried out and adapted by some outstanding masters in the art of printing. For which purpose we have come to an agreement with the following far-sighted men who are devoted to us in Christ and whom we sincerely esteem: Stephan Dold, Georg Reiser and Johannes Beckenhub, alias Mentzer – these being most experienced masters in this art – and we have brought them to our city of Würzburg on the basis of contracts and equal terms. To them alone and to no one else have we given the opportunity to print accurately and in the best possible way these liturgical books (as indicated above, including those for the choir). We have taken them and their families, their goods and chattels, under our dutiful and paternal protection and defense. Therefore, so that fuller faith might reveal itself to all thanks to such a printing of the books, we have ordered and allowed the master printers to decorate the canonical books which are to be printed in the manner mentioned above with the insignia of our Pontificate and Chapter.6

Bishop Rudolf invited Strasbourg residents Georg Reyser, Stephan Dold, and Mainz cleric Johannes Beckenhub to establish a printing shop in Würzburg, the central city within his duchy. Though Reyser had a thriving printing business in Strasbourg with his relative Michael and had acquired citizenship there in 1471, he left the town of 40,000 to move to Würzburg, a town of a few thousand, to accept a monopoly on printing with the primary goal of the production of reformed liturgical texts. There is no evidence that Reyser purchased property in Würzburg, and the terms of the contract – protection of goods and chattels – suggest that his home and printing shop were in the bishop’s residence.7 The first book to be issued in Würzburg was a folio breviary for the diocese, and Dold, Reyser and Beckenhub are listed in the colophon. The edition is dated after 20 September 1479, the date of the contract, but it is likely that it came off the press the following year.

Reyser printed thirteen editions of service books for Würzburg with two sizes of gothic plainchant type: nine missals, an agenda, a Vigiliae mortuorum, a gradual, and an antiphonal (see Table 1.1 in the Appendix). In addition he printed in 1482 the first missal for the diocese of Mainz. His Very Large Antiphonal type was created for the Würzburg choirbooks of the 1490s, spaciously laid out on nine staves per page (see Plate 1). The strong verticality and regularity of the neumes are proof that the bishop had made a good investment in the Strasbourg printers. Note the tightly abutting staff segments that make up the staves and the regularity of the double lines at the margins. Each of the punches for plainchant in an extant fifteenth-century set at the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp is six inches long, a size thought necessary for the large designs of a choirbook.8 The engraver had to carve lines that extended to the very ends of the steel punch so that printed segments would abut, unlike most type characters such as the clef signs that were carved in the centre of a punch, to be surrounded by space on a piece of type.

Georg Reyser was the Hofbuchdrucker and as such probably wore the livery of the bishop on fine occasions, as did Gutenberg in Mainz. About one-half of his printed editions were devoted to government printing, broadsides or short pamphlets about laws and official news. His press and types would have been the property of the bishop and his work would have been done only upon the order of the bishop. Rudolph subsidised and controlled the press, and paid for the creation of two sets of music punches as well as alphabetic types of extremely fine design. Only after Rudolph’s death was Georg awarded the right of citizenship by his successor, after which he printed a few songs and other works in German before his death in 1504.9

Eichstätt: Michael Reyser and Prince-Bishop Wilhelm von Reichenau

Our next example is Michael Reyser, the relative of Georg who is described as the owner of the house in Strasbourg in which their printing shop was located. By 1479 Georg Reyser had moved to Würzburg to serve Rudolph. In that same year he was awarded citizenship in the duchy of Eichstätt, southeast of Würzburg. The bishop of Eichstätt commissioned Georg to print in Würzburg two breviaries for Eichstätt in 1483 and 1484.10 But the bishop’s plans for Georg seem to have changed, and Michael would move to Eichstätt instead of Georg.

Michael is not mentioned in Georg’s contract with the Würzburg bishop, but we know that he was an important part of the printing operation there because of a letter written by Bishop Rudolph in 1480 (April 25) to the magistrate and city council of Strasbou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures and music examples

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Music printing and publishing in the fifteenth century

- Part II Printing techniques: problems and solutions

- Part III Music printing and commerce

- Part IV Music printing and intellectual history

- Index