![]()

Section 1

Contemporary Wicked Challenges to Health and Social Care

Becoming increasingly popular in both academic and societal discussions, the approach to problematize ‘wickedness’ serves as a critical and thought-provoking tool to address and rethink current concerns in the management of health and social care. The first section of the book provides background for understanding wicked problems in a broad sense, starting with insightful reflections on the concept itself and continuing by critical contemplation of important policy-level social issues.

Harri Raisio, Alisa Puustinen and Pirkko Vartiainen deepen our knowledge of the concept of wicked problems and offer insights on how to apply this approach to the context of health and social care management. Next, Will Thomas and Susan Hollinrake take a stand on reforms of social care, a concern faced in many countries. Challenges resulting from reforms are considered from the perspective of service users and professionals and mirrored against the ethical aspects. Janet Carter Anand, Gavin Davidson, Berni Kelly and Geraldine Macdonald highlight a topical worldwide social policy issue, the personalization of care, and challenge us to call into question whether it is always the preferred way to meet the individual and diverse needs of people with disabilities. Using personal budgets as an example, the authors of this chapter claim that, regardless of its benefits, personalization may be a contentious and troublesome concept—and a wicked solution to wicked problems.

![]()

1 The Concept of Wicked Problems

Improving the Understanding of Managing Problem Wickedness in Health and Social Care

Harri Raisio, Alisa Puustinen and Pirkko Vartiainen

Editors of three scientific journals point out in their recent joint editorial that “health care leaders at all levels are faced with some of the most complex and challenging problems confronting leaders” (Hutchinson et al. 2015, 3021). More precisely, they write of wicked problems and call for moral courage in tackling problem wickedness. As researchers deeply involved with wicked problems, we share this view and strive to further process the significance of wicked problems in managing health and social care. Our aim is to increase the understanding of the sources of problem wickedness and to explore the implications for leaders in health and social care.

This article consists of four main sections. In the first section, we will define the concept of wicked problems in detail. We also consider the conceptual criticism and provide examples of wicked problems found in the health and social care sector. The second section scrutinizes the conceptual expansions of wicked problems, such as the super wicked problem, wicked ethics, and the wicked game, and assesses their relevance from the health and social care perspective. In the third section, we will deepen the theoretical foundations of the concept of wicked problems by affiliating wicked problems to the complexity science framework. As complexity can be a source of problem wickedness (see Zellner and Campbell 2015), this is an essential aspect of the analysis. The fourth section focuses on the leaders’ point of view. Hutchinson et al. (2015) point out the challenge of defining leadership “when there are no easy answers.” We conclude with a summary of key insights.

Defining a Wicked Problem

The concept of wicked problems1 already has a 50-year history. In 1967, an esteemed systems scientist, C. West Churchman, hosted a seminar series at the University of California, Berkeley.2 In his account of what occurred, Skaburskis (2008) reports how German-born faculty member Professor Horst W. J. Rittel made a presentation at one seminar session that included a description of the differences between social and technical problems, using what came to be known as the ten main features of wicked problems. Churchman himself became interested in the concept and wrote a guest editorial titled Wicked Problems for Management Science (Churchman 1967).3 This was the first reference to wicked problems in the academic literature. Rittel took several years to present his arguments in article form, but finally, in 1973, with his colleague Melvin M. Webber, he published the seminal article Dilemmas in the General Theory of Planning in Policy Sciences.4 Today (June 7, 2017), Google Scholar records more than 10,000 citations of the article. Although there are major continental differences on the level of awareness about the concept of wicked problems (Xiang 2013), the overall interest in the concept “seems greater than ever”5 (McCall and Burge 2016, 200; Danken, Dribbisch and Lange 2016). This is understandable, as the problems we face seem to be in increasing numbers wicked by their very nature (Raisio and Lundström 2015). The dilemma, however, is that these problems are often thought to be tamer than they really are, or the problems are understood as wicked, but even then, the chosen approaches are more like approaches required to address so-called tame problems (Rittel and Webber 1973; Raisio 2009).

Rittel and Webber noted that “the problems that scientists and engineers have usually focused upon are mostly ‘tame’ or ‘benign’ ones” (1973, 160). The concept of tame problems offers a form of counterpart to the concept of wicked problems. Tame problems can be defined thoroughly and permanently. There is little or no ambiguity. It is relatively easy to reach a common understanding of such problems, so conflict situations are rare. In addition, it is obvious when a tame problem has been solved; there is a clear end solution, and its accuracy can be evaluated objectively. Solving a tame problem is in practice a repetition, in the sense that someone with enough expertise and specialization and using proven solution processes could repeatedly solve similar problems (King 1993; Roberts 2000). It is often also the case that one can start solving tame problems from the beginning, without any major impact, as if the process took place in laboratory conditions. Overall, solving a tame problem can be understood as a rather linear process proceeding step-by-step from problem definition, through gathering information and analysis to identifying different solutions, after which the best solution to the problem is identified and then implemented (Conklin 2005). Think, for example, of an experienced mechanic fixing a familiar model of car.

Wicked problems resist such approaches, as is clear from the ten characteristics attributed by Rittel and Webber (1973) to such issues (see Table 1.1). Owing to the explicit overlapping between the different characteristics, several researchers have condensed them further (see e.g., Conklin 2005; Norton 2012; Xiang 2013). However, Danken, Dribbisch and Lange (2016, 16–17) critique the lack of a clear-cut definition for the concept, as well as the fragmented debate on problem wickedness. Their systematic quantitative literature review strives to collate the existing academic literature so that “we as scholars know what we are talking about when we talk about wicked problems” and thus would be “able to enter more purposefully into a discussion on their management.” Three dominant and interrelated thematic clusters of wicked problems’ core characteristics emerge from the above review: the challenge of problem definition; non-resolvability; and multi-actor environments.

The challenge of problem definition refers to the cognitive uncertainty (van Bueren, Klijn and Koppenjan 2003) and the content complexity (Stoppelenburg and Vermaak 2009) related to problem wickedness. Wicked problems are by nature so multidimensional, interrelated and ambiguous that understanding them is a considerable challenge. The major uncertainty arises from a lack of knowledge or understanding of the problem and also the solutions; the identification of cause-effect relationships is a particularly challenging exercise (McCall and Burge 2016). Non-resolvability refers to the chronic nature of wicked problems. As Danken, Dribbisch and Lange (2016, 16–17) write, “scholars hold that any attempt to resolve [wicked problems] may exacerbate the problem, reveal new aspects of the problem, and/or generate additional, often unanticipated problems.” This is to be understood as a problem of demarcation (see Skaburskis 2008). Waves of consequences can be such that the comprehensive evaluation of solutions becomes virtually impossible (McCall and Burge 2016).

Table 1.1 The Ten Original Characteristics of Wicked Problems (Rittel and Webber 1973) - There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem. Different approaches to the problem see it differently. Different proposed solutions reflect the fact that it is defined differently.

- There is a ‘no stopping rule.’ Unlike in an experiment where you can stop natural processes and control variables, you cannot step outside a wicked problem or stop it to contemplate an approach to answering it. Things keep changing as policy-makers are trying to formulate their answers.

- Solutions are not true or false, rather they are good or bad. There is no right answer, and no one is in the position to say what is a right answer. The many stakeholders focus on whether proposed solutions are ones they like from their point of view.

- There is no test of whether a solution will work or has worked. After a solution is tried, the complex and unpredictable ramifications of the intervention will change the context in such a way that the problem is now different.

- Every solution is a ‘one-shot operation.’ There can be no gradual learning by trial and error, because each intervention changes the problem in an irreversible way.

- There is no comprehensive list of possible solutions.

- Each wicked problem is unique, so that it is hard to learn from previous problems because they were different in significant ways.

- A wicked problem is itself a symptom of other problems. Incremental solutions run the risk of not really addressing the underlying problem.

- There is a choice about how to see the problem, but how we see the problem determines which type of solution we will try and apply.

- Wicked societal problems have effects on real people, so one cannot conduct experiments to see what works without having tangible effects on people’s lives.

|

Multi-actor environments refer to the social complexity related to problem wickedness (Conklin 2005). When scholars refer to social complexity, they usually speak of the range of people involved and their diversity, which means the actors concerned have a variety of worldviews, political agendas, educational and professional backgrounds, responsibilities and cultural traditions. This diversity makes the extent of social complexity within the wicked problem overwhelming in most cases (Weber and Khademian 2008). These multi-actor environments include strategic and institutional uncertainty (van Bueren, Klijn and Koppenjan 2003). Strategic uncertainty arises from the presence of a multitude of actors, each with their own perceptions of the problem and the solution, creating many different and sometimes conflicting strategies. Institutional uncertainty develops from the existence of many different arenas—from the local to the global—where wicked problems are discussed. Danken, Dribbisch and Lange (2016, 28) use the three thematic clusters to devise the following formulation of the concept of wicked problems: “[wicked problems] are chronic public policy challenges that are value-laden and contested and that defy a full understanding and definition of their nature and implications.”

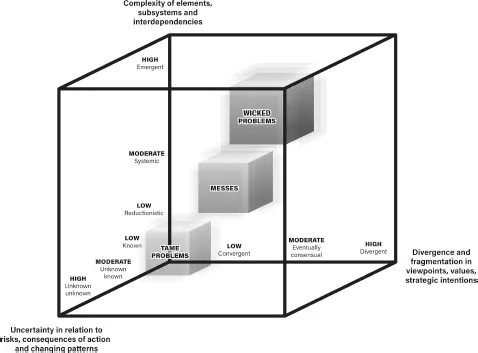

One significant question debated is the issue of degrees of wickedness. For example, Conklin (2005) considers that problems can be wicked even if they do not include all the original ten features. For Southgate, Reynolds and Howley (2013), while some characteristics might not be as clear as others, it is the sum of these individual characteristics that make the problems wicked. Norton (2012, 450) highlights the involvement of conflicting values as the underlying unifying threat of all the characteristics of wicked problems: “while the characteristics [Rittel and Webber] list for wicked problems are quite disparate, the class of wicked problems are all expressions of diverse and conflicting values and interests, which cause individuals to view problems very differently” (italics in the original). For Head (2008, 103), this “divergence and fragmentation of viewpoints, values, strategic intentions” alone might not be enough to make a problem wicked, and an additional high level of “complexity of elements, subsystems and interdependencies” and “uncertainty in relation to risks, consequences of action, and changing patterns” is required. These three dimensions of a problem’s wickedness are depicted in Figure 1.1 in the form of a Wickedness Cube.6 The cube works as a simplified illustration, highlighting the ideal models of three different types of problems.7 The differentiation of problem types is not as clear-cut in reality as it appears in the cube and in the ideal types described. Boundaries of the ideal types most often blur due to situational dynamics. Problem types are not static but constantly re-evaluated as part of the dynamic, complex contextual variations.

Figure 1.1 A Wickedness Cube

Tame problems are situated in the bottom left rear corner of the cube. These are issues that can be examined through a reductionist approach. They can be broken into parts and fixed in isolation from other problems. Tame problems are also issues that ‘enjoy consensus’ (King 1993, 106), in the sense that they are convergent. Additionally, the consequences of solving a tame problem are known; for individuals who specialize in solving a particular tame problem, there is no uncertainty around what will happen. In addition, so-called messes8 are added to the cube and situated at the center of the model. Messes can be understood as clusters of problems that cannot be solved in isolation. As King (ibid.) states, “messes demand a commitment to understanding how things going on here-and-now interact with other things going on there-and-later.” A systemic approach is needed. This means examining patterns of interaction among the different parts of the problem as well in other, related problems. To illustrate the point, a human mission to Mars is necessarily messier than fixing a car; however, it is still an issue on which consensus could eventually be achieved, at least on some level. After enough time studying the problem, we can, for example, begin to agree on appropriate strategies to go forward. Messes call for interdisciplinarity, which aids not only in formulating solutions, but also in reducing the uncertainty related to the messes. This uncertainty can be depicted as unknown knows, meaning that we may not have the knowledge of risks, consequences of actions, or changing patterns, but some other experts might (see Aven 2015).

Wicked problems are situated close to the top right front corner of the cube. These are emergent issues, meaning that even examing patterns of in...