![]()

Part I

Multimodality in the Classroom

![]()

1

Braving Multimodality in the College Composition Classroom

An Experiment to Get the Process Started

Dawn Lombardi

I offer a focused definition of new media as texts that juxtapose semiotic modes in new and aesthetically pleasing ways, and in doing so, break away from print traditions so that written text is not the primary rhetorical means.

—Cheryl Ball (2004, p. 403)

Introduction

It is odd that I find myself writing on multimodality, considering I just completed my first multimodal assignment with my students five months ago. Previously, I had never heard the word “multimodal.” I am one of the older writing instructors at my institution—51 as of this writing—and I consider myself only semi-computer savvy. But I found myself in a new composition classroom fully equipped with laptops for student use and thought there must be more that we can do with this technology than simple word processing. At about the same time, my son, a high school sophomore, came to me with an English class essay assignment the likes of which I had never seen. I remember thinking that his teacher must be very progressive to assign such an essay. Surely, she is fresh out of college and a Google Docs/Flash Player/Photoshop whiz, none of which I can claim to be. As we sifted through his assignment, I noticed that the essay required components that lay outside of the standard formal essay that I was accustomed. It required other forms of media besides printed text; instead, it used various modes to create meaning. The idea both fascinated and perplexed me. Adding pictures and audio and hyperlinks to an essay? How does one go about creating such an essay? Where does the writing occur? And, finally, how is his teacher going to grade such a thing?!

I did not realize it then, but what I was seeing for the first time was a multimodal essay assignment, a project that teachers of English and other disciplines have been assigning in their classrooms for the past two decades. These teachers know that our students were raised in a technological age and do practically everything electronically. They also realize that if we are to prepare them to become members of the writing public and to negotiate life, and to provide a successful environment for learning and creating meaning, we must provide multimodal assignment opportunities in our classrooms. In her 2004 address at the Conference on College Composition and Communication, Kathleen Blake Yancey called for change regarding composing processes in the composition classroom. “Composition in a new key,” she said, requires instructors to consider the question, “What is writing, really?” (2004b, p. 298). It obviously includes print, but composing is no longer only about the medium used. It is also about technology.

Many instructors have answered Yancey’s call for change. However, there are those of us who find change difficult. In fact, a change in praxis and pedagogy can be downright unnerving. And it is not just a change in how, why, or what we teach. It is a change in viewing the simple printed text as a thing of the past; it is the realization that a progressive classroom with a dynamic learning environment requires us to learn new skills to teach what we have always taught; it is a metacognitive assignment turned around on us, the instructors, where some of us now must come to grips with the idea that we do not know all that we thought we knew about teaching composition; and it is the fear of braving a new frontier where we will make mistakes and blunders, perhaps even embarrass ourselves.

So how do instructors like me go about contemporizing our college writing classrooms? How do we hop on the digital media bandwagon with our peers? We know that our students are light years ahead of many of us in the technological arena, so how are we to teach them when we barely understand it ourselves? The first step is to realize the importance of what I mentioned earlier: a progressive classroom with a dynamic learning environment. It requires us to learn new skills to teach what we have always taught, and currently that is considerably more than reading and writing. Elizabeth Daley, dean of the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts declares, “No longer can students be considered truly educated by mastering reading and writing alone. The ability to negotiate through life by combining words with pictures, audio, and video to express thoughts, will be the mark of the educated student” (as cited in Yancey, 2004b, p. 305). Selfe and Hawisher (2004) make a compelling argument when they say, “If our profession continues to focus solely on teaching only alphabetic composition—either online or in print—we run the risk of making composition studies increasingly irrelevant to students engaging in contemporary practices of communication” (p. 72). It is our job to educate our students. We ask them to learn new content, to strive for excellence, to think outside of the box. If we ask that of our students, then we must be willing to do it ourselves. With this realization, I ventured to experiment.

The Experiment

I like to call the assignment that I re-created for my students “the Experiment” because, in essence, it was. It was also fascinating, educational, unnerving, complex—but it was something I never tried before in my classroom. I had several different options for designing it; I had choices to make for implementing and assessing it; I also had no certainty of its results. I knew that it would benefit my students by providing options for them to create meaning through various media, and that was good enough for me. I sent an e-mail to my son’s teacher, asking her permission to use the assignment. She wholeheartedly agreed and graciously offered her assistance if I needed it.

As I said earlier, like many older college writing instructors, I consider myself only semi- computer savvy. I know my way around Word and Google Docs. I have become acquainted with two different university learning platforms. I have created PowerPoints (but not Prezis). I now respond electronically to students’ essays, all of my grading is digitized, and for the first time, I am tracking attendance online. What I can do digitally is a much shorter list than what I cannot, and yet I decided to give this multimodal/multigenre assignment a try.

The following pages narrate the assignment—from introducing it to students to its conclusion and assessment. I provide details, humbly including my successes and stumbles, and ask that readers bear in mind that I was unaware of something called “multimodality” when I implemented this assignment. (Now, of course, I am a big fan). Here I walk through the steps of the assignment, noting those places where I now feel changes could be made for a better experience for both the instructor and the students. The figures include my assignment slides along with one student’s essay to serve as a fine example of the types of multimodal essays my students created.

The Introduction

When I first introduced the assignment to my students, I prefaced my lecture with a caveat with which they were already familiar: I am a bit “electronically challenged.” I politely informed them that, although I wanted to try a new assignment idea with them, there was the possibility that I might need their help at some point with the technology they used to create it. They agreed without hesitation. Next, I explained to them, with Freire’s idea of critical pedagogy in mind, that I wanted their permission to try a new assignment with them. It was an experiment, so to speak, involving the use of their computers to write an essay, but their essay was going to have more than just prose. It would have several parts—not necessarily several pages but several parts. These parts would incorporate various things such as moving and still images, audio recordings or soundbites, colorful graphs, maps, posters, and many different genres that they were going to create in between their written texts to help create meaning. The assignment required them to be creative and allowed for innumerable topics and story lines.

Then I asked if anyone considered himself or herself to be creative? I asked this because I realize that not all students feel that they are particularly clever or innovative. In a general education course such as first-year composition, we get all majors and types of students, not just the creative writers. I did not want to instill panic in those students before I got the assignment off the ground. Thankfully, 17 out of 19 students raised their hands. I asked the two students who did not raise their hands why they felt they were not creative, and their answers were not surprising. They both said they did not “like creative writing.” I assured them that, because they were in control of the story line and topic of their essays, they would not find the assignment too painful. As members of a community of writers in the classroom, they would have the creative input of the entire class if they got into a bind. That appeased them, and so I proceeded to lay the groundwork. Here is the foundation of the assignment that I presented to the class:

Pretend that you are your current age and gender, but you are living in another historical time period. It can be any place that you choose, but it must have a critical social issue that you will research, define, explore, and analyze. You can be either a participant in or an observer of this critical issue. You will produce a PowerPoint essay in which you create a fictitious story about yourself: your name, your heritage, your family and friends, your occupation, your hometown, etc., and anything else you choose to write about concerning the place and time in which you live. You will create original documents that may or may not have text such as photographs, audio recordings, map, charts, and graphs. You must do some research to incorporate factual information about the time period and the critical issue, but the story line you create about your life will be fiction.

I will be honest and say that there were mixed responses to the assignment. Some faces in the room lit up; I could see the creative juices beginning to flow. Others, however, groaned a bit at the idea of creating something with components and “parts.” One student actually asked, “Can’t we just write a normal paper?” I looked at her with wide eyes and asked, “Seriously? Why would you choose to write a plain old essay when you can create something really cool using all of the technology you have at your fingertips?” She replied, “Because it sounds like a lot of work!” I believe I gave a little lecture about how all writing is work and that all things worthwhile take effort. This chapter was going to change the way they looked at the composing process—and it did. That student, by the way, turned out to be one of the biggest fans of the assignment. She did not create the best essay, but the effort she put into it showed her that she had more creativity than she initially thought. That was a great lesson in itself.

It is important to note here that I have always let my students choose the topics on which they write formal essays in my classroom. The assignment may have a general theme, such as the historical one I describe here, with guidelines and parameters so the students know what is expected of them. However, I give students a lot of room to initiate, experiment, explore, design, and develop their ideas. My belief that students produce their best writing when given the opportunity to choose the topic is steeped in research (see Hayes & Flower, 1986; Applebee, 1982; Britton, 1975; Shaughnessy, 1977) as well as in my own experiences throughout the years as a student, teacher, and writer. We all write best when we are interested in the topic.

The Multimodal Assignment Components

The multimodal assignment is divided into six parts or components—Prospectus, Prologue, Original Works, Repetends, Notes Page, and Works Cited. A seventh component, Research, was included in the original assignment, and I incorporated it in my lesson, but I now regret that decision. This is one “stumble” that I would change. A lesson on research should be completed before the students begin this assignment, if they have not already learned about scholarly research. The students will explore a particular time period and a relevant critical issue associated within that time period, and they must have the ability to locate reliable sources of information before beginning their research.

The Prospectus

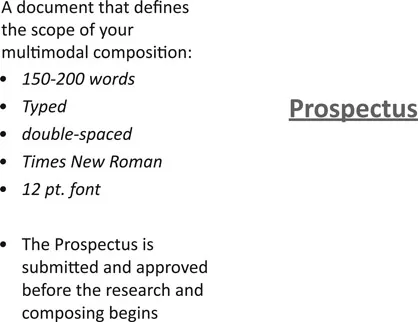

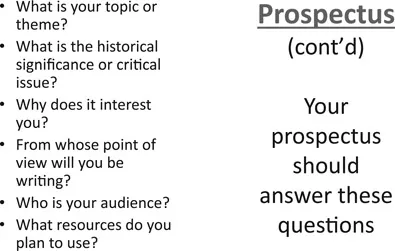

A Prospectus is a document describing the major features of a proposed work (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2). It is the first component of this assignment, and I asked the students to complete it and get my approval before they continued. The Prospectus serves two purposes: (1) it provides an organizational strategy, an initial framework for the students to begin outlining, creating, and designing their assignment and (2) it allows me to see the students’ plan of action before they get too far into the research and find that their chosen topic or critical issue is not really what they wanted or thought it was going to be, is too broad or too narrow a topic, etc.

Figure 1.1 Prospectus Part I

Figure 1.2 Prospectus Part II

I initially assigned the Prospectus as the first slides of the PowerPoint, but here, again, I stumbled. The Prospectus serves as a design element. It should be viewed as such, as a separate part of the assignment rather than a beginning or introduction to the essay. This is where the student describes the essay’s topic and theme, and defines a fictional character, point of view, historic time period, and critical issue. The second component of this assignment, the Prologue, has much of the same information as the Prospectus, but it serves as an introduction. When coupled in the PowerPoint,...