![]()

Part 1

What and for what is governance?

- Chapter 1. Introduction: the problem with sustainability governance

- Chapter 2. Three governance styles and their hybrids

- Chapter 3. Governance failures and their causes

- Chapter 4. Introducing metagovernance: governance of governance

![]()

1 Introduction

The problem with sustainability governance

Ultimately, this is all about governance. About inclusiveness: societies will only accept transformation if people feel their voices have been heard. And it’s about breaking out of silos. Sustainable development is not just an economic or social challenge, or an environmental problem: it’s all three – and our efforts on each need to reinforce rather than undermine one another.

– First Vice-President of the European Commission Frans Timmermans at the United Nations Summit on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in New York, 27 September 2015

1.1 Holistic governance meets holistic goals

Ten years ago, I wrote a research book showing that successful public managers applied a flexible, situation-adapted approach to achieve their objectives; five case studies in different countries underpinned this conclusion. For these public managers, such situational governance was a logical thing to do. It was similar to the approach coined decades ago as ‘situational leadership’ of employees (Hersey and Blanchard, 1988), which still figures in most leadership training. From experience, they had learned that each policy or implementation challenge requires a situational and dynamic approach, just as employees need guidance adapted to personality and circumstances, to get the best out of them. Many scholars call the application of such a context-specific approach to policy challenges ‘metagovernance’ (i.e. governance of governance). In my research, four case studies on environmental protection showed that public managers tackled the same policy topic in different countries with a different (but dynamic) governance framework. A fifth case study on inner security (community policing) suggested that metagovernance also happens in other policy areas.

One decade later I think that one of the added values of Public management and the metagovernance of hierarchies, networks and markets (Meuleman, 2008) has been the discovery that metagovernance is not only a theoretical concept. In fact, it is a still relatively ill-researched good practice of public management, and beyond this: also private sector and civil society organizations practice metagovernance. The challenge that springs out of this insight is that this ‘good practice’ needs further development into a (public) management method for combining different governance styles into tailor-made governance frameworks. Since 2008, I have presented and discussed metagovernance theory and practice at dozens of lectures and workshops, and practiced this approach in my daily work as line, project and process manager of national and European policy processes. At the same time, academics have published hundreds of research articles on the use of metagovernance as analytical, design and/or management tools for complex issues. Metagovernance has become accepted as a relevant political science concept (Bevir, 2011, Jessop, 2011, Rayner, 2015, Larsson, 2017) and scholarly literature utilizing the term has become abundant. The first reason to write this book was therefore to review recent literature in the light of the evolving theory and practice of metagovernance.

The second reason to write this follow-up book was to seek answers to the reverse of the central question of the first book, for which I had interviewed successful public managers: is it plausible that unsuccessful public managers are, generally spoken, not using a metagovernance lens to prevent and mitigate governance failures? What can we learn from the failures we can identify through metagovernance glasses?

The third and most important reason to write this book was that I was curious to see how the holistic concept of metagovernance could be applied to the most holistic of contemporary policies: the quest for sustainable development, and in particular for implementation by 2030 of the 2015 UN Agenda 2030 with its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). After several decades of working with the concept of sustainable development, the Rio+20 conference in 2012 and its outcome, the 2015 SDGs, can only be considered as a huge achievement of the UN and of the international community of member states, civil society, private sector and academia. The governance of the process to formulate strong but still commonly accepted Goals and targets through the ‘Open Working Group’ (OWG) was innovative at this scale, as the inside account of the process reveals:

The OWG began its work at a time of frustration with multilateral sustainable development negotiations and long-standing mistrust between North and South. The experience of the OWG helped to rebuild this trust and improve multilateral negotiations in the UN system. Although not all of the techniques used by the OWG are replicable, such as the troika system, the notion that UN negotiations can experiment with new procedures and do not have to be wedded to the past is a major contribution of the OWG.

(Kamau et al., 2018)

The joint work resulted in Goals and targets which are designed in a very smart way, in order to make them ‘indivisible’.

Implementation of the SDGs requires in the first place readiness of public sector organizations and political leaders to design and manage effective governance. This requires rethinking of institutions, instruments and governance processes on at least the same scale as the rethinking of energy, economy, food and other systems that are essential for living well within the limits of the planet.

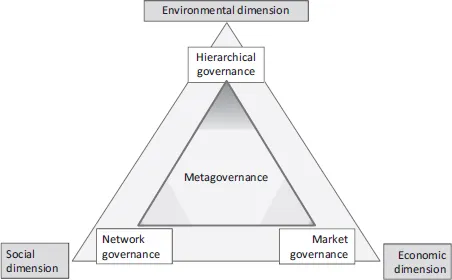

Sustainable development is about creating balances between the environmental, economic and social dimensions of life, also with a view to future generations. The three dimensions should be seen as communicating vessels: it is impossible to take them apart without facing consequences. Sustainable development is therefore a ‘meta-policy’ (Meadowcroft, 2011). The parallel is that metagovernance has also three dimensions: it is about creating balanced combinations of tools from three different governance styles, notably hierarchical, network and market governance. In isolation, these styles are weaker than in carefully designed combinations. Jordan (2008) argued that sustainable development and governance may be “the most essentially contested terms in the entire social sciences” – hardly a good foundation, one might think, for solid and insightful scholarship. With metagovernance the complexity is even greater.

Figure 1.1 combines the triangle of metagovernance and the triangle of the sustainable development dimensions, which immediately brings forth the question what the affinity is of each of the three sustainability dimensions with each of the three governance styles. Is it a coincidence that both holistic concepts are often presented as having three dimensions, modes or styles? How closely are the three pairs – environmental governance and hierarchy, economic governance and market governance, and social governance and network governance – related? This is something we need to find out. Of course, each of the sustainability dimensions can be dealt with using all governance styles but on first sight, there is this underlying preference: environmental policies traditionally rely on legislation; economic governance favours market-style instruments; and the social dimension shares key values with network governance.

Figure 1.1 Sustainable development and metagovernance: holistic goals meet holistic governance

The holistic nature of both parts of the focus of this book – metagovernance and sustainability, respectively the Sustainable Development Goals – necessitates an approach which is essentially multi-, inter- and transdisciplinary. Concepts and examples will be used from various social science disciplines and from various practices. In addition, how people argue, think, feel and dream and what drives them to action or non-action is an essential but often neglected part of the discussion on governance. Governmental organizations are built with and upon people – which is one of the reasons maybe why they can behave rationally one day and irrationally the next day. The reason to address this human dimension of governance and metagovernance of sustainable development is a very pragmatic one: it is because it happens to be influential in practice.

To conclude, what this book aims to achieve is bringing together new insights and practical solutions as regards the use of metagovernance to improve sustainability policies and their implementation, with the SDGs as main application case for the medium term (i.e. until 2030).

1.2 Sustainability governance: key terms

When the First Vice-President of the European Union’s executive, the European Commission, spoke at the United Nations General Assembly on 27 September 2015, he emphasized the governance dimension of sustainable development, and in particular of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Also from the academic perspective it has been argued that sustainable development is above all about getting the governance right (Meadowcroft, 2011, p. 536):

Sustainable development is really all about governance. The idea was formulated because of dissatisfaction with existing (‘unsustainable’) development patterns. And the assumption was that conscious and collective – i.e. political – intervention would be required to shift the societal development trajectory on to more sustainable lines.

This sounds simple as a starting point, but the difficulty is that the term governance has many meanings. Different people – scholars and practitioners alike – have defined governance in various and, quite often, mutually excluding ways. I use a broad definition of governance, which is in short that governance is how societal challenges are tackled and opportunities are created; in Sections 1.3 and 2.1, I will explain why. This definition focuses on the question of ‘how to get things done’, not on ‘what should be done’. This goes back to the classical distinction in political science between polity, politics and policy. Governance is about polity (institutions) and politics (processes), and not about policy (the substance). For me as a public administration practitioner, this distinction makes sense. Others argue that policy should be part of governance. Governance then becomes “a social function centred on steering individuals or group toward desired outcomes” (Young, 2017, p. 31). This view is relatively often seen in academic discourse on environmental governance.

Sustainable development is a laboratory for governance innovation (how will goals be achieved?), but also for policy innovation (which concrete goals need to be set in a specific situation?). Policy and governance are two sides of the same coin – the ‘coin’ being how to tackle effectively societal challenges. Within this line of thinking, governance is not an end, but a means to an end. Governance without carefully crafted policy is useless but policy without adequate governance cannot be implemented and is therefore without practical meaning, or put differently: governance needs policy and policy needs governance.

Although effective governance is essential for effective policy, the latter is usually politically more attractive because it is more visible for citizens. This makes sense: people who excel in a craft, be it a painter, carpenter, teacher or a medical doctor, will not become famous because of how they do it, with which tools etcetera, but because of what they do or achieve. Governance, however we define it, is often perceived as boring, talking shop, abstract and/or bureaucratic: citizens, politicians or the media are not interested in the craft of governance, which I am not sure is a problem. There are exceptions to this rule, when a perceived policy failure turns out to be in fact a governance failure: when bureaucratic procedures, lack of transparency, lack of efficiency or corruption prevent a policy to deliver the expected output or outcome. This dual complexity as regards policy and concerning go...