eBook - ePub

Transforming Disability Welfare Policies

Towards Work and Equal Opportunities

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Transforming Disability Welfare Policies

Towards Work and Equal Opportunities

About this book

Bringing together contributions from institutions such as the OECD, the WHO, the World Bank and the European Disability Forum, as well as policy makers and researchers, this volume focuses on disability and work. The contributors address a wide range of issues including what it means to be disabled, what rights and responsibilities society has for people with disabilities, how disability benefits should be structured, and what role employers should play. Fundamental reading for specialists in disability, social protection and public economics, and for social policy academics, researchers and students generally, Transforming Disability Welfare Policies makes an enormous contribution to the literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Transforming Disability Welfare Policies by Christopher Prinz, Bernd Marin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Politique sociale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction:

1. Main Findings and Conclusions from the OECD Report — and Critical Queries

Disability Programmes in Need of Reform

OECD

Summary

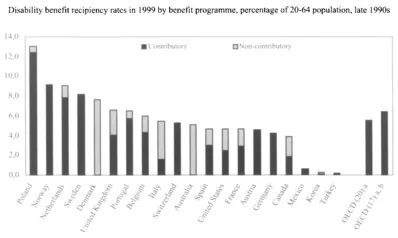

OECD countries spend at least twice as much on disability-related programmes as they spend on unemployment. Disability benefits on average account for more than 10% of total social spending. In the Netherlands, Norway and Poland they reach as much as 20%.

In spite of such high spending, disability rates remain stubbornly high. In most countries, people who enter disability-related programmes remain there until retirement. This is expensive, inefficient and encourages segregation. Persons with disabilities often wish to participate actively in society and are capable of doing so, given the opportunity, the necessary training, and support.

The low employment rate of people with disabilities reflects a failure of government social policies. Societies hide away some disabled individuals on generous benefits. Others isolate them in sheltered work programmes. Efforts to help them find work in the open labour market are often lacking. The shortcomings affect moderately disabled individuals, as well as those with severe handicaps, but are particularly true for people over age 50.

Recent research in 20 countries found none to have a successful policy for disabled people. But many employ innovative measures which, taken together, point toward a comprehensive policy that emphasises economic and social integration. We propose reforms to move disability policy closer to the philosophy of successful unemployment programmes, based on five key features:

- recognise the status of disability independent of the work and income situation,

- emphasises putting people to work,

- restructure benefit systems,

- introduce a culture of mutual obligations,

- require individuals to make a concerted effort to find a job, if they are capable of working,

- give a more important role to employers.

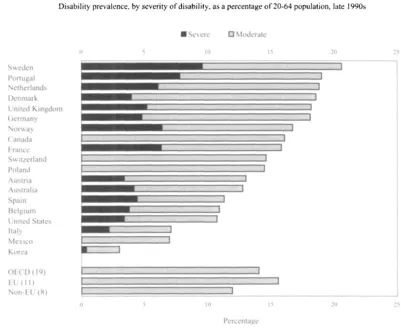

Why Is Disability on the Rise?

In the general public, disability is often equated with severe handicaps, such as visual, hearing and mobility problems that require substantial aids and workplace adjustments. Severe disabilities, however, affect only about one third of the working-age disabled, and congenital disabilities account for only a small minority of cases. The majority of the working-age disabled suffer from diseases and problems that have arisen while at work. Many diseases are stress-related, muscular, and cardiovascular. Mental and psychological problems are on the rise: they are at the origin of up to a third of disability benefit cases in OECD countries.

Disability rates have been increasing in almost all OECD countries and policy efforts to help persons with disabilities return to work have hardly been successful in any of the countries. But there are still large differences in the nature and incidence of disability across countries. Some examples illustrate the range of problems encountered in member countries:

- In the Netherlands, the proportion of young women between the ages of 20 and 35 who receive disability benefits is three times higher than for their male counterparts.

- In Austria persons over 55 years are more frequently on disability benefits than in any other country, while rates for Austrians under age 50 are much lower than elsewhere

- In Norway, disability benefit rates are much higher but unemployment benefit rates are much lower than elsewhere. Norway spends more than 5.5% of GDP on disability-related programmes - more than 12 times the amount spent on unemployment.

Figure 1: Average Disability Prevalence of 14%, of Which One Third Are Severely Disabled Note: Sum of "Severe" and "Moderate" for Canada, Mexico, Poland, Switzerland and unweighted averages. Source: See Annex 1, Table A1.1.

Why Do Disability Rates Vary so Much from Country to Country?

Why is there such a large difference in disability rates across countries that enjoy similar levels of economic and social development? It is difficult to imagine why young Dutch women would be in so much poorer health than young women in other countries, or why older persons in Austria or Norway are so much more likely to become disabled than people in other countries.

The country-by-country comparisons in the study suggest that the ways in which disability is defined and assessed, and the ways in which benefits are awarded, have a strong impact on the numbers of people on benefit rolls. Countries with generous benefits, and where many people had access to them, tend to have higher disability rates, the study found.

Disability rates also depend on the ease of access to other out-of-work programmes. In the United States and the United Kingdom, for example, disability benefits became more heavily used when entry to other programmes, such as unemployment or early retirement benefits, became more restricted.

In many countries, disability awards are highly concentrated among people over age 50. This reflects the fact that disability becomes more frequent as people age. It also shows a tendency in some countries to park unemployed workers in disability programmes until they reach retirement age. Paradoxically, in countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands a surprisingly large proportion of those receiving benefits are young people.

A key reason government disability outlays remain so high is that very few people actually leave benefit programmes. The numbers are virtually nil in all countries studied, despite big efforts by some governments to rehabilitate and reintegrate persons with disabilities. Even in the United States and Australia, where substantial monetary incentives are offered to those who leave benefit rolls for work, few individuals do so.

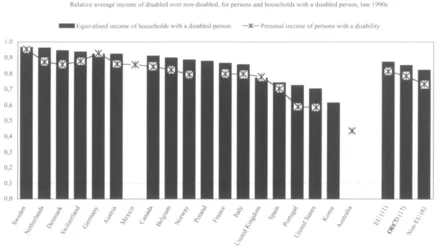

Figure 2: Successful Economic Integration in Many but Not in All Countries Notes: Countries are ranked in decreasing order of the ratio of equivalised incomes of households with a disabled person over those without. No personal income data for Korea and Poland, and no household income data for Australia and Mexico.

How to Get Persons with Disabilities into Employment?

Employment rates for persons with disabilities are low. Severely disabled people, disabled persons over the age of 50 and disabled people with low levels of educational attainment are least likely to be employed. Most countries offer special employment programmes for people with disabilities. These programmes are important for some groups, especially the severely disabled. However, they do not have a large-scale impact on overall employment rates of persons with disabilities.

In addition, integration programmes strongly discriminate against older disabled persons. Vocational rehabilitation and training are offered almost exclusively to people below the age of 45, which partly explains why so many older people are found in disability benefit programmes. But even special employment programmes, such as sheltered workshops or subsidised forms of employment, are also geared to mostly young and severely disabled persons.

Figure 3: Disability Benefit Recipiency Rate Concentrated at 5 to 7% Note: The rate is corrected for persons receiving both contributory and non-contributory benefits, except for Canada (unknown).

a) Contributory and non-contributory benefits.

b) Excluding Mexico, Korea and Turkey. Source: OECD database on programmes for disabled persons, see Annex 1, Table A1.2.

Overall, vocational rehabilitation and training is offered too seldom, and often initiated too late. More should be done to involve employers in this process. The average per capita cost for vocational rehabilitation and training is low compared to the average cost of disability benefits. Given that such programmes help secure permanent employment, the investment should quickly pay for itself.

Different employment policy approaches seem to have similar effects. While legislated approaches to employment promotion differ - some are rights-based, while others are obligations-based, or rely on incentives - all approaches tend to benefit people already in employment much more than those who are out of work. Some countries oblige employers to hire a certain percentage of disabled persons, however such rules work only if tough sanctions are imposed on companies that fail to comply.

Finally, there is a close relation between employment rates of disabled people and those of non-disabled people. This suggests, first, that general labour market forces have a strong impact on the employment of people with disabilities and, second, that general employment-promoting policies also foster the employment of special groups in the labour force, such as people with reduced work capacity.

What Are the Policy Conclusions?

Although no single country in this review has a successful overall policy for disabled individuals, researchers drew on the experience from specific programmes in some countries to make the following recommendations.

Recognise the status of disability independent of the work and income situation.

Societies need to change the way they think about disability and those affected by it. The term "disabled" should no longer be equated with "unable to work". Disability should be recognised as a condition, but it should be distinct from eligibility for, and receipt of, benefits. Likewise, it should not automatically be treated as an obstacle to work. The disability status, i.e. the medical condition and the resulting work capacity, should be re-assessed at regular intervals. The recognised disability status should remain unaffected by the type and success of intervention, unless a medical review certifies changes.

Some countries have recently moved in the direction of uncoupling an individual's disability status from his or her ability to receive benefits. Countries use different terminology, such as "linking rules" (United Kingdom), "let the pension rest" (Denmark) or "freezing a disability pension" (Sweden) to refer to the possibility of keeping the disability status while trying to work. Individuals also retain the option to go back on benefits should they lose their job, or should work not be acceptable.

Introduce a culture of mutual obligations. Most societies readily accept their obligation to make efforts to support and integrate disabled persons. However, it is less common to expect disabled persons themselves, or employers, to contribute to the process. This change of paradigm will require many countries to fundamentally rethink and restructure the legal and institutional framework of disability policy. Moreover, it will only be effective if it is accompanied by a change in the attitude of all those involved in disability issues.

Participation in vocational rehabilitation, for instance, is compulsory in a number of countries (Austria, Denmark, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and in a mitigated form also in Germany and Norway), and disability benefit settlement is conditional upon completion of the vocational rehabilitation process. In most cases, however, this obligation is administered with great flexibility and subjectivity, e.g. as to the age or the employment experience of the disabled person.

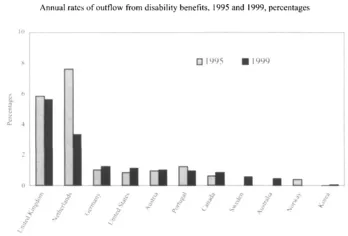

Figure 4: Low Outflow Rates from Disability Benefits Note: Countries are ranked in decreasing order of the 1999 rate.

Source: OECD database on programmes for disabled persons, see Annex I, Table A1.2.

Design individual work/benefit packages.

Merely looking after the financial needs of disabled people through cash benefits is insufficient. That approach would exclude many individuals from the labour market, and sometimes from society more generally. Therefore, each disabled person should be entitled to a "participation package" adapted to individual needs and capacities. This package could offer rehabilitation and vocational training, job search support, benefits, and the possibility of different forms of employment (regular, part-time, subsidised, or sheltered). It could also in some circumstances contain activities that are not strictly considered as work, but contribute to the social integration of the disabled person.

Some countries, for example Germany and Sweden, have tried to ensure access to a wider range of disability-related services through legislation that entitles disabled persons to certain services. More permanent on the-job support is necessary for many disabled persons participating in the regular labour market. Support measures, such as individual job coaches and personal help for work-related and social activities, appear to have strong potential. In Denmark, for example, a personal assistant can be hired to assist in occupational tasks.

Introduce new obligations for disabled people.

Benefit receipt should in principle be conditional on participation in employment, vocational rehabilitation and other integration measures. Active participation should be the counterpart to benefit receipt. Just as the assisting caseworker has a responsibility to help disabled persons find an occupation that corresponds to their capacity, the disabled person is expected to make an effort to participate in the labour market. Failure to do so should result in benefit sanctions. Any such sanctions would need to be administered with due regard to the basic needs of the disabled person and those of dependent family members. Furthermore, sanctions would not be justified in any case where an appropriate integration strategy had not been devised, or proves impossible to formulate, e.g. because of the severity of the disability.

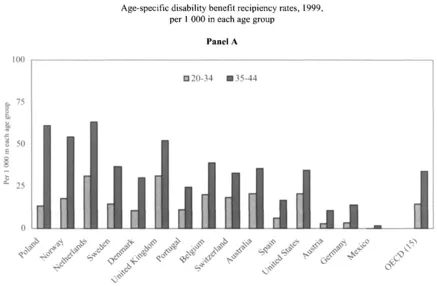

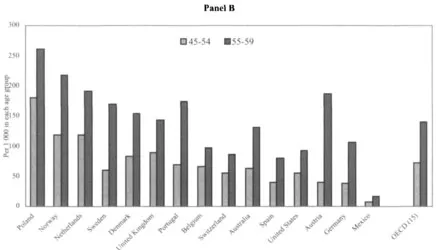

Figure 5: Remarkable Age Differences in Benefit Recipiency Note: Countries are ranked in decreasing order of the 1999 recipiency rate for 20-64 years old. Different scales in panels A and B to make cross-country differences visible.

Source: OECD database on programmes for disabled persons, see Annex 1, Table A1.2.

Involve employers in the process.

Involving employers is crucial to the successful re-integration of disabled persons. Different approaches exist, ranging from moral suasion and antidiscrimination legislation to compulsory employment quotas. In Italy, employers were recently made responsible for assigning the disabled person equivalent tasks. Swedish employers must provide reasonable accommodation of the workplace or, if possible, a different job in the company. In Germany, employers have a general obligation to promote the permanent employment of disabled employees, and in France, employers with at least 5,000 employees are obliged to offer training to make sure that persons hit by a disease or an accident can keep a job in the same company. The effectiveness of these measures depends on the willingness of employers to help disabled persons enter the workforce, or stay there.

Promote early intervention.

Early intervention can in many cases be the most effective measure against long-term dependence on benefits. As soon as a person becomes disabled, a process of tailored vocational intervention should be initiated, including job search assistance, rehabilitation, and further training. Where possible, such measures should be launched while the person is in an early stage of a disease ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: 1. MAIN FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS FROM THE OECD REPORT - AND CRITICAL QUERIES

- 2. OPENING STATEMENTS

- THEME 1: WHAT Do WE MEAN BY "BEING DISABLED"?

- THEME 2: WHAT RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES FOR SOCIETY AND FOR PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES?

- THEME 3: WHO NEEDS ACTIVATION, HOW, AND WHEN?

- THEME 4: HOW SHOULD DISABILITY BENEFITS BE STRUCTURED?

- THEME 5: WHAT SHOULD AND WHAT CAN EMPLOYERS DO?

- BARRIERS TO PARTICIPATION: A SESSION ORGANIZED BY THE EUROPEAN DISABILITY FORUM / EDF

- NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS