![]()

Part 1

Labor and Law

![]()

1 Trading identities

Balthasar Sturmer's Verzeichnis der Reise (1558) and the making of the European Barbary captivity narrative

Mario Klarer

Balthasar Sturmer’s Verzeichnis der Reise (1558)—most likely the first European Barbary captivity narrative—tells the story of a young German merchant who, as a galley slave of the Turks, happened to experience the 1535 Habsburg siege and conquest of the city of Tunis. Despite the fact that this narrative is among the earliest specimens of this text type, it is one of the most extraordinary. With 78 handwritten pages, it is not only an extensive early modern white slavery narrative but also a most unusual and prolific text with respect to narrative technique, plot development, authorial voice, and autobiographical individualism. It is hard to believe that this text was not intended for publication and it is even harder to understand why this text did not make it into print. It contains all the features of the narratives that were later successfully disseminated by English, French, and German publishers, starting in the second half of the sixteenth century and continuing to be published into the early nineteenth century. In layout, scope, and basic intention it is virtually indistinguishable from the printed narratives. On the contrary, in its vividness, personal self-reflection, narrative voice, composition, and irony it seems rather like the culminating point of this genre than one of its earliest examples.1

Even a crude plot summary reveals the extraordinary nature of Sturmer’s account. After having idly spent the proceeds of an entire shipload of wheat, which he sold for his father in Lisbon, Balthasar Sturmer enlists on a ship that raids Turkish vessels. When he becomes aware of the amount of money that can be made from a single captured vessel, he suggests to his shipmates that they invest their money in a galley and become self-employed professional pirates. However, the day after they agree on this business plan Turkish pirates seize their ship, kill half of the crew, and sell the survivors into slavery. As a galley slave among Turkish troops, Balthasar takes part in two major sieges of the city of Tunis. Both times he is a prisoner of the Turks, and in one instance he is even forced to fight against his Christian brothers. After regaining his freedom, when Emperor Charles V takes possession of Tunis in 1535, Balthasar becomes a member of an expedition to Peru and accumulates considerable riches but eventually loses everything after returning to his father in Germany.

Sturmer’s text, similar to other Barbary Coast narratives, tries to embed the narrator’s personal story within the context of larger geopolitical events.2 In this case, Sturmer witnesses the military conflicts between Christian forces under the Habsburg Emperor Charles V, who is supported by the fleet of the Genoese Andrea Doria, and Muslim forces under the command of the pirate Chaireddin Barbarossa, a vassal of the Osman Sultan Suleiman II. Despite adopting, at times, a larger geopolitical point of view in the narrative that is reminiscent of a historiographer, Sturmer primarily provides a deeply personal and autobiographical account of his adventures as an “extra” in this larger theater of history.

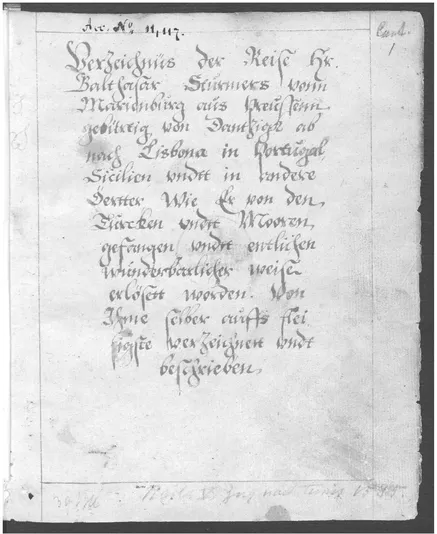

Even the title page (see Figure 1.1) with its long explanatory title is absolutely typical of later printed captivity narratives, as well as of novel-like personal histories in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries:

Account of the travels of Mister Balthasar Sturmer. Native of Marienburg in Prussia, from Gdańsk to Lisbon in Portugal, Sicily, and many other places. How he was captured by the Turks and Moors, and finally released in a wondrous manner. Assiduously chronicled and described by himself.

(f. 1r)

It seems as if the sentences on the first folio page are not simply the opening lines of a private journal, but rather a conspicuously crafted book title, which makes it likely that the author intended some sort of publication or wider dissemination. As the manuscript has a separate title page, including the name of the author and a short synopsis of the plot, which is very similar to the narrative title pages of early novels, it is likely that Balthasar had a wider public in mind. The first folio contains the title-like text on the recto side and is left blank on the verso side. This otherwise unexplainable waste of paper also supports the assumption that it was intended as a book-like title page in the sense of a marketing paratext.

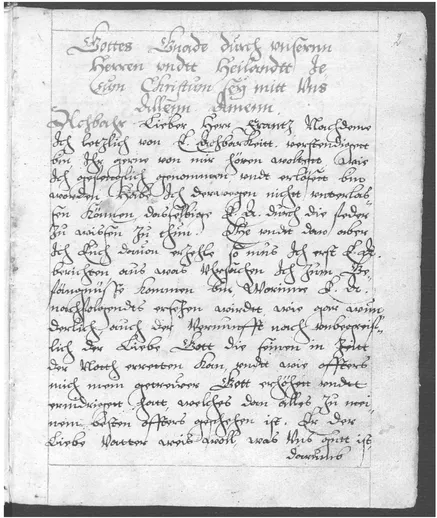

This first folio is followed by two pages, folio 2r (see Figure 1.2) and 2v, which correspond to what in a printed narrative would be the dedication or the preface. In this part, Sturmer directly addresses an unspecified “Herr Frantz,” whom he also refers to as “Eure Achtbarkeit,” which literally translates as “Your Honor.” This otherwise unidentified Mr. Frantz apparently requested or asked for an account of how Balthasar was “captured and released” (f. 2r).

The remainder of the two preface-like pages allegorizes Balthasar’s adventures in a religious manner. Here as well, Sturmer’s text is in line with other specimens of this genre, most of which frame the actual captivity narrative by exemplifying the narrator’s personal history as a manifestation of God’s will or providence. In this religiously motivated opening section, Balthasar – the merchant’s son – continues using the diction of accounting and commerce that he already introduced in the title. “Verzeichnis,” the first word of the title, means “account,” “directory,” “index,” “record,” or “register.” Now, in the dedicatory opening part, he refers to sins committed by using the German word for “register.” “He, Our Good Father, knows well what is good for us and therefore chastises us frequently. In the beginning, we might think

Figure 1.1 Title page of Balthasar Sturmer, Verzeichnis der Reise (1558); f. 1r

Source: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz. © bpk-Bildagentur.

Figure 1.2 Balthasar Sturmer, Verzeichnis der Reise (1558); f. 2r

Source: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz. © bpk-Bildagentur.

we are not being treated properly, but when we look at our register, we realize that we actually deserved a harsher punishment than the one we have endured” (f. 2r-v; emphasis added). Balthasar frames his own account, or “register,” of misdeeds and punishments by arguing that God has to penalize our sins, but also by pointing out that “Our Good Lord also wants to forgive the misdeeds of men when they show repentance for their sins” (f. 2v). He ends this two-page prologue or preface by referring to his adventures as “exempla” of misdeed and punishment. Since God’s relation to man is, according to Balthasar, similar to a business transaction and based on a balance-sheet-like arrangement, he ends the section with a reference to the exchange of goods: “I would also like to speak further of the trade” (f. 2v) that is “the circumstances through which I came into captivity” (f. 2r). As we will learn, trade in the widest sense of the term is the reason for all his adventures and misfortunes.

In the narrative proper, which starts on folio 3r, Balthasar tells the story of his adventures that began when he, as a merchant’s son, sailed from the port of Danzig (Gdańsk) in Prussia to Lisbon in order to sell a shipload of wheat on behalf of his father. Danzig was the most important seaport in the early sixteenth century for distributing wheat from northern to southern Europe. This development was in part caused by capital investors, such as Jakob Fugger in Germany, who successfully curbed the monopoly of the Hanse by supporting competitors outside the Hanseatic union (Steinmetz 112). Despite successfully carrying out his father’s business and making a considerable amount of money, equivalent to the annual salary of a sailor, Balthasar ends up penniless. He claims that “victuals are very expensive there” (“sehr theure Zehrung”; f. 3r), which is most likely a euphemism for having squandered all his money. “After the money had vanished, I thought to myself, ‘How can I return home empty-handed?’” (f. 3v). This question could either mean that he would have to return to his father without the proceeds of the business transaction or that he was not even able to pay for his fare back to Danzig. The latter seems more likely.

When a German gunsmith offers him a position as his assistant on a vessel bound for Sicily, he jumps at the opportunity. In Sicily, he enlists in the Armada of Emperor Charles V against the Turks. In this capacity, he experiences the siege of the Balkan city of Coron, in which the Habsburg fleet with the aid of the Genoese Andrea Doria is able to defeat the Turkish ships that had blocked the harbor and besieged the castle. The Habsburg forces free the trapped Spanish soldiers in the city of Coron, who “had been deprived of any real food for so long that they resembled ghosts. Indeed, their victuals had run out countless weeks before, and they had been feeding on cats and rats since” (f. 5v-6r).

After this adventure, Balthasar enlists on a Maltese galley, which sets out to seize Turkish vessels. In other words, Balthasar voluntarily joins European pirates who are preying on Turkish ships or goods. This part of the narrative is quite extraordinary and unusual when compared to later Barbary captivity narratives. Most European narratives try to polarize the readers through black-and-white stereotyping in which the Muslim corsairs prey upon innocent Christian ships. The mention of European piracy or privateering would muddy the otherwise clear distribution of roles with Christians as victims and Muslims as villains. Therefore, most published captivity accounts do not openly acknowledge that piracy was a bilateral phenomenon in the early modern Mediterranean, carried out by Christian and Muslim forces alike. Slave markets existed on the Christian side, for example, in Malaga, Marseille, Livorno, and Malta, and on the North African side in Tripoli, Algiers, Tunis, and Salé. North African pirates, who operated from the Ottoman satellite city-states of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers, or the independent kingdom of Morocco, were by no means the only ones responsible for Mediterranean piracy and captivity in the early modern period. The Knights of Malta, for example, were key Christian players in Mediterranean privateering and human trafficking.3 Sturmer’s narrative is remarkable since it gives an authentic account of the actual situation in the early modern Mediterranean with respect to corsairing and privateering as an economic factor that escapes religious binaries.

The Maltese piracy enterprise in which Sturmer participates is so successful that after the capture of the first Turkish vessel, the crew are already rich men. However, things change swiftly when soon after that successful venture three Turkish galleys attack their ship. Balthasar narrates how they engage in a battle with the Turks, how they defend themselves, and how the Turkish pirates “finally came on board the third time around; [. . .] assailed us and conquered our ship with everything she contained” (f. 9v).

In this moment of extreme suspense, when we learn that they fell prey to the enemy and when we are eager to hear what became of them, Balthasar brings the gripping narrative to a halt. Similar to a cliffhanger, he digresses into a flashback in which he tells us about the plans he and the crew had forged out the day before. After having seized the aforementioned huge bounty from the Turkish trading vessel, Balthasar and the crew members contemplated what they should do with the large amount of money which was now at each man’s disposal.4 Some of the men felt that it would be a good idea to transfer the money through a bill of exchange (“Wexsell” f. 9v) to the city of Antwerp.5 But Balthasar tried to convince the crew otherwise: “Why do you want to go home already? We should first try our luck once more and sail to Sicily again, buy a galley there or have one built, and be on our way and amass even more booty. Then we can return home in triumph!” (f. 10r). In other words, Sturmer tried to talk the sailors into engaging in an independent business venture in which they would invest all their money in a galley and become self-employed corsairs. The crew agreed to this proposal and made a deal to put this plan into execution.

Balthasar concludes this short but strategically well-placed flashback and digression by writing: “Thus it was decided in good will, but the tables were about to turn, as they say: Homo proponit, Deus disponit [Man proposes, but God disposes]” (f. 10r). When the narrative comes to this major climax—that is, when Balthasar is captured by the Turks and is about to lose his freedom—he brings the narrative to a halt and provides us with a possible reason for God’s punishment in his flashback. We have to remember that in the preface Balthasar had claimed that he is giving us a “register” of sins and their punishment. “I have to report [. . .] the circumstances through which I came into captivity [. . .] and how many times my Faithful God elevated and humbled me” (f. 2v). Balthasar was elevated by God when he received the rich bounty from the vessel they captured, but he fell victim to his own hubris when he was not satisfied with the large sum of money and wanted to quench his lust for even more riches as a self-employed corsair. What is interesting is that his loss of freedom is somehow again coupled with issues of business. We should not forget that he had set his mind on starting his own little piracy joint venture. The punishment for his avarice follows en suite—the next day to be precise, when the Turks take him and his fellow crew members captive.

After this short one-paragraph digression from the description of the attack by the Turkish galleys, we learn that half of Balthasar’s fellow crew members, 23 in total, were killed during that hostile encounter and that some “who were still alive but had been wounded were thrown overboard” (f. 10r). Balthasar, who was also seriously injured, escapes this fate by a hair’s breadth: “I was badly wounded myself but pretended to be in better condition than I actually was; I would have hated to come in aquam [into the water]” (f. 10r).6 Having survived despite his injuries, the victorious Turkish pirates sell him as a slave for 40 ducats the next day and a little later he is resold on the island Djerba near Tripoli for 32 ducats as a galley slave.

Balthasar Sturmer’s ensuing account as a rower who is “chained” (f. 10v) to a Turkish galley provides astonishing information about the piracy trade, for example, that their ship was able to capture “fifteen Christian ships within three weeks” (f. 10v). After this time Balthasar is sold for the third time, and, as a galley slave on a ship that will become part of the Turkish admiral Barbarossa’s fleet, he has to participate involuntarily in the major battles taking place in the mid-1530s in North Africa. Thus, Balthasar’s personal narrative enters the stage of world history of which he is able to provide a very idiosyncratic perspective fro...