![]()

Part I

Liminal processes

Beyond the wild and the domestic

![]()

1

A genetic perspective on the domestication continuum

Laurent A. F. Frantz and Greger Larson

Introduction

Beginning with dogs over 15,000 years ago, the domestication of plants and animals has played a key role in the development of modern societies. The importance of domestication for archeology, biology and humanities means that it has been studied extensively. Over the past decades, new conceptual models of animal domestication have emerged from the archeological literature that is trying to break away from anthropocentric view of domestication. These models describe domestication as a gradual process, but also question the ubiquity of human intent during the early stages of the process (Vigne 2011; Zeder 2011; Ervynck et al. 2001). Under this view, domestication is thought as a continuous process by which a species alters, voluntarily or involuntarily, the phenotype of another and assumes a significant degree of influence over its care and reproduction (Zeder 2015). These models stand in stark contrast with the traditional views that involve intent and strong directed breeding from humans (Larson and Fuller 2014; Clutton-Brock 1992; Bökönyi 1989).

This view of domestication also refrains from generalising a process that might be highly species specific (Vigne 2011). This is done by broadly defining three pathways to domestication: commensal, prey and directed pathway, each with different varying degree of intent (Zeder 1982). Under the commensal pathway, for example, domestication is most diffuse and involves little intent, while under the directed domestication is fully intentional with human directed breeding starting during early phases of domestication. In the latter model, humans apply a strong dichotomy between what is considered wild and domestic.

The striking morphological and behavioural changes associated with the process of domestication also make it an excellent model to study evolution. Understanding the broad mechanisms that allow for fast evolution in domestic taxa is a central question in evolutionary biology. In contrast with species specific pathways to domestication advocated by some archeologists and biologists, however, are often more interested in drawing conclusions that are globally applicable to the process than species specific. For example, multiple studies have focused on understanding common biological features (e.g. developmental processes) underlying a general “domestication syndrome” in both plants (Sakuma et al. 2011; Allaby 2014) and animals (Wilkins et al. 2014; Sánchez-Villagra et al. 2016). This is an interesting contrast between “archeological” and “biological” views of domestication.

Genetics have been instrumental in studying biological aspects of domestication. For simplicity, however, genetic studies generally model domestication as a process involving strong bottlenecks (also called founder events), reproductive isolation between wild and domestic, and strong artificial selection. These models provide a great framework for geneticists to address questions such as geographic origin, strength of selection and demography of domestication (Frantz et al. 2015). This view of domestication, however, implies strong control of the breeding of domestic species as well as strong artificial selection that also stands in contrast with the archaeological view of domestication as a more fluid process.

Armed with new DNA sequencing technologies, geneticists are now able to sequence and analyse large scale genetic information from both modern and archeological samples. These genomes provide an ever greater resolution to address fundamental questions about domestication, and in particular to test the veracity of recent theories. Here we first discuss how genetics can provide key information to test various models of domestication, and then review the degree to which genetic evidence supports these models.

Models of domestication and their expectations

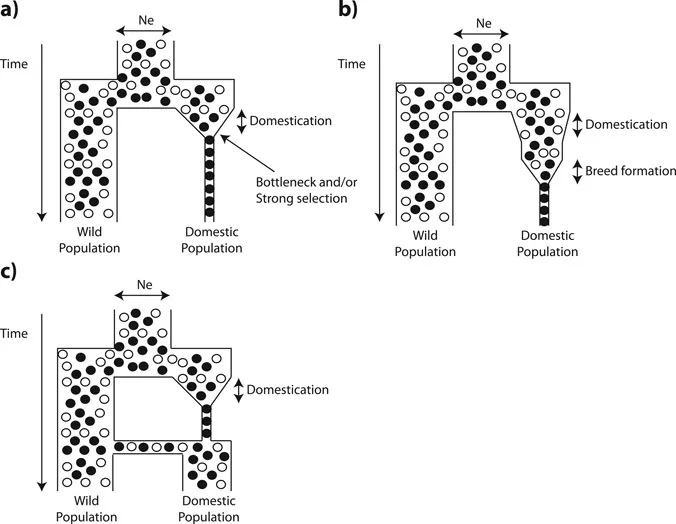

Conceptual models of domestication based on the idea of intent involve a combination of key characteristics: 1) a founder effect (also called a bottleneck; see Figure 1.1a) as only a few individuals are domesticated (Larson and Burger 2013; Eyre-Walker et al. 1998; Doebley et al. 2006); 2) strong artificial selection for traits that define domestic species (e.g. behaviour; Figure 1.1b) (Trut et al. 2009; Trut 1999); 3) reproductive isolation enforced between wild and domestic population to facilitate trait differentiation (e.g. keep animals tame; Figure 1.1c) (Marshall et al. 2014); and 4) simpler genetic architecture of traits (Andersson-Eklund 2013). While these characteristics provide a great framework for geneticists to study domestication, as key events (e.g. geographical origin and timeframe of domestication), they do occasionally contradict the expectations associated with the more diffuse models of domestication proffered by archeologists (Marshall et al. 2014; Vigne 2011; Zeder 2011).

The first and maybe most obvious difference between these models of domestication is the expected strength of bottlenecks. Figure 1.1a is a schematic of a model in which a wild population undergoes a “domestication” bottleneck as a result of a human-directed domestication. In this example, the wild population prior to domestication has two alleles (black and white). After domestication, however, only the black remains, as the result of a founder effect (since the founding population possessed only the black allele). While drastic, this example highlights one major expectation of a directed model with human intent: a severe bottleneck resulting in a significant loss of genetic diversity. Bottlenecks can, as we will see later in this chapter, also result from directed breeding (for example, during the formation of a specific breed) as highlighted in Figure 1.1b. In a more diffuse model, however, in which domestication proceeds unintentionally, the expectation is that a domestication bottleneck will be less severe (or even absent). This is because the process will happen somehow more “naturally” and thus more individuals will be involved in the founding of the domestic population and will have more chance to capture an equal number of black and white alleles.

Figure 1.1 Schematic of various models of domestication and their effect on genetic diversity.

Conscious selection by humans for specific traits is also expected to reduce genetic diversity. In our example in Figure 1.1a, the white allele could be represented by aggressive individuals. Strong “artificial” selection would be applied against these individuals in a domestic population. On the other hand, if domestication proceeds unintentionally, selection is not expected to be as strong simply because individuals that are, for example, aggressive (or simply less tame) will not be directly selected against. The expectations of a directed model of domestication, as opposed to a more diffuse model with no intent, are rather similar to the one of severe/mild bottlenecks: differential level of genetic diversity (Figures 1.1a, 1.1b).

Another expectation of directed models of domestication is the maintenance of reproductive isolation (prevent breeding between wild and domestic population). As we show in Figure 1.1c, gene flow (exchange of genetic material) between wild and domestic populations can increase genetic diversity. If conscious selection is applied on a domestic population, people might have imposed strict reproductive isolation from wild populations. Preventing gene flow from wild animals would provide a framework for faster selection of domestic traits (Frantz et al. 2015). On the other hand, without conscious selection, domestication proceeds similarly to parapatric speciation models which can (and often do) involve gene flow (Larson and Fuller 2014; Frantz et al. 2015; Vigne 2011). By taking advantage of modern DNA sequencing, geneticists are now able to generate the necessary data, including genomes from modern and archeological samples, to test these key expectations underlying intentional models of domestication.

Domestication, genetic diversity, bottlenecks and breed formation

Genetic studies of domestication often assume a domestication bottleneck in both plants (Xu et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2007) and animals such as dogs (Freedman and Wayne 2017; Frantz et al. 2016; Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005), cattle (Bollongino et al. 2012; Scheu et al. 2015; Beja-Pereira et al. 2006; MacLeod et al. 2013), goats (Gerbault et al. 2012) and rabbits (Carneiro et al. 2014). The idea of a domestication bottleneck is so embedded in the genetic literature that it is often taken as prior knowledge (Bollongino et al. 2012; Scheu et al. 2015; Gerbault et al. 2012). For at least some species, genetic data has supported the idea of a lower genetic diversity in domestic populations, especially dogs (Marsden et al. 2016), cattle (Bollongino et al. 2012; MacLeod et al. 2013) and rabbits (Carneiro et al. 2014). Dogs are the most drastic example, especially as breed dogs are significantly more inbred than wolves (Frantz et al. 2016; Marsden et al. 2016).

Interestingly, in dogs, most genetic diversity is thought to have been lost during severe bottlenecks linked to breed formation (Wang et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2014) and therefore may not reflect processes that took place during domestication itself. Domestication may have induced a reduction of genetic variation of less than 20% (Wang et al. 2014). Recent breeding efforts in purebred dogs have thus resulted in more severe bottlenecks than domestication itself, as indicated by the higher level of genetic diversity observed in free living dogs (village dogs; see Marsden et al. 2016). This more recent and drastic bottleneck, however, does not explain all differences between wolves and dogs, suggesting that a milder bottleneck took place during domestication (Marsden et al. 2016). The exact timing of this earlier bottleneck and therefore its association with dome...