![]()

Part I

Cultural Pedagogies of Girlhood

![]()

1 Recess Queens

Mean Girls in Graphic Texts of Girlhood

If those girls knew how I loathed their company, they would not seek mine as much as they do.

—Charlotte Brontë1

In Alexis O’Neill and Laura Huliska-Beith’s 2002 picture book The Recess Queen, Mean Jean towers over her classmates and offers a malicious, thin-lipped half-grin that hints at the torment she plans to inflict. On the opposing page, classmates look up at her and even the trees on the hillside lean away from her blustering presence. A bright yellow sky contrasts with the periwinkle of the playground that turns darker behind the body of Mean Jean, signaling the large physical and emotional shadow that the girl casts. Mean Jean’s body takes up the entire left side of a two-page spread. Next to her feet lay a basketball and baseball bat, tools of intimidation and pain. The text reads:

Mean Jean was recess queen and nobody said any different. Nobody swung until Mean Jean swung. Nobody kicked until Mean Jean kicked. Nobody bounced until Mean Jean bounced…. If kids ever crossed her, she’d push ‘em and smoosh ‘em, lollapaloosh ‘em, hammer ‘em, slammer ‘em, kitz and kajammer ‘em.

Mean Jean rules with physical violence: she launches a child into the air by stomping on the end of a seesaw, and bounces a boy like a ball. One of her peers hides under the slide and reads The Art of Self Defense. Mean Jean continues to bully her classmates until a new girl named Katie Sue, who lacks knowledge of the playground power dynamics, asks her to play. The other children stand back in awe as Katie Sue jumps rope and chants, “I like ice cream, I like tea, I want Jean to Jump with Me!”

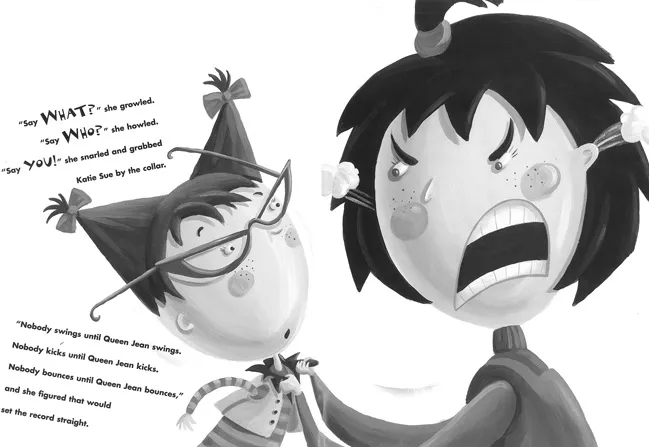

This invitation prompts Mean Jean to grab Katie Sue. Jean’s face takes up a full page, her eyebrows furrow, and steam comes out of her ears. The ponytail on the top of her head explodes up and off the page (Figure 1.1). “‘Say WHAT?’ she growled. ‘Say WHO?’ She howled. ‘Say YOU!’ She snarled and grabbed Katie Sue by the collar.”

In a quick turnaround, Jean softens to Katie Sue’s overtures, and overcomes her meanness. “Jean doesn’t push kids and smoosh kids, lollapaloosh kids, hammer ‘em, slammer ‘em, kitz and kajammer ‘em—‘cause she’s having too much fun rompity-romping with her FRIENDS.” The book ends as it began with a double-paged spread that mirrors the opening image. A smaller, smiling Jean carries a student on her shoulders, and reaches her other hand out in friendship. The concluding page shows Jean and Katie Sue moving into the distance, their feet high off the ground as their jump ropes break the frame of the bright and cheerful yellow landscape inside which they hop. A reviewer for Publishers Weekly aptly points out that The Recess Queen is “story about the power of kindness and friendship” (“Review of The Recess”). Indeed, Mean Jean has been disciplined through and into kindness.

The Recess Queen appeared on bookshelves in 2002, the same year as Rachel Simmons’s Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls and Rosalind Wiseman’s bestselling self-help book, Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends and Other Realities of Adolescence upon which Tina Fey based her screenplay for the popular 2004 film Mean Girls. In contrast to characters like Mean Jean who outwardly express anger through physical violence, Simmons and Wiseman claimed that a “hidden culture of aggression” dominated girls’ relationships. They focused on relational aggression—“any behavior that is intended to harm someone by damaging or manipulating relationships with others using tactics such as rejection and social exclusion” (Crick and Grotpeter 711).2 In the mean girl discourse boys are defined as physical and girls as relational aggressors. This gendered framework normalizes indirect meanness as girlish behavior and simultaneously pathologizes girls’ physical violence and anger, like that demonstrated by Mean Jean, as deviant femininity (Brown, Girlfighting 1).

In the post-2002 mean girl moment, texts about the relational girl-bully continue to proliferate. To contextualize the representation of mean girls in contemporary graphic texts of girlhood, I begin with a discussion of Eleanor Estes and Louis Slobodkin’s classic 1944 illustrated novel The Hundred Dresses, which was rereleased in 2004. An analysis of a set of exemplary picture books and comics published during the height of the mean girl boom follows, including Jacqueline Woodson and E.B. Lewis’s Each Kindness, Patricia Polacco’s Bully, Fanny Britt and Isabelle Arsenault’s critically acclaimed graphic novel Jane, the Fox and Me, and Rachel Renée Russell’s best-selling cartoon series, Dork Diaries.3 Highly visible and popular, contemporary graphic texts about mean girls deflect attention away from larger systemic inequities and circulate within the school curriculum as a socially acceptable form of misogyny.

The Post-2002 Mean Girl Moment

In the 1970s Norwegian scholar Dan Olweus noted the prevalence of bullying in school in his landmark scholarship. Children’s and young adult (YA) fictions support Olweus’s findings as the schoolyard bully has been and continues to be a popular antagonist.4 The post-2002 burst of mean girl texts runs parallel to larger trends in publishing for children, specifically an increased attention to bullying in North America. The April 1999 Columbine shootings, and a number of high profile cases of cyberbullying, as well as events such as the bullying prevention conference held at the White House in 2011 led to an increase in children’s and YA books about bullying.5 In a 2013 article for The New York Times, Leslie Kaufman points out that “according to WorldCat, a catalog of library collections worldwide, the number of English-language books tagged with the key word ‘bullying’ in 2012 was 1,891, an increase of 500 in a decade” (“Publishers”). Bullying stories continue to thrive, and the relationally aggressive mean girl is now a stock character.6

This has not always been the case. In a content analysis of one hundred picture books, Patrice A. Oppliger and Ashley Davis found that “percentages of physical aggression were mostly identical for males (48.1%) and females (48.6%). On the other hand, females (28.3%) were much more likely to use social exclusion than males (9.5%)” (520). Their findings suggest that although characters like Mean Jean are as likely to be as physical as their male counterparts, relational bullies that engage in tactics like gossip, social exclusion, and cyberbullying are overwhelmingly female.7

Contemporary mean girl narratives draw on regressive ideas about femininity, such as early twentieth-century psychologist and educator G. Stanley Hall’s contention that boys’ physically aggressive behavior was normal while “young women’s aggression manifested itself in inappropriate behaviors that were often projected onto other young women” (Beals 60). The theorization of girls as the opposite of boys and as psychologically rather than physically aggressive has deep roots. Scholars have debunked the idea that “different kinds of aggression can be understood simply in terms of gender stereotypes (the mean, covertly aggressive, and manipulative girl and the proto-male, direct, and more transparent boy)” as a myth (Artz et al. 310). Regardless, images of and narratives about the mean girl continue to circulate as fact; and, certainties about girls’ relational aggression play out in school discipline policies, legal cases, and in mainstream media accounts even when evidence suggests otherwise (Ryalls).

Mean schoolgirls are ubiquitous characters in children’s texts, films, academic studies, curriculum, and highly circulated pop-psychology books like Wiseman’s Queen Bees and Wannabees. With few exceptions, mean girl characters and their targets tend to be privileged white girls, like Regina George in the film Mean Girls, while girls of color, such as Chastity Church in 10 Things I Hate About You or Zoe Franklin in the Dork Diaries series usually fill the role of one of the main character’s side kicks. Queer characters are also ambiguously outside of explicit whiteness and figure as outsider group support and as targets of bullying for characters like Cady Heron in Mean Girls.8

Recycling Mean Girls

Post-2002 narratives draw on and make reference to earlier visual-verbal constructions of the mean schoolgirl. To trace this history, I begin with Eleanor Estes and Louis Slobodkin’s Newbery award-winning illustrated novel The Hundred Dresses, which focuses on Polish immigrant Wanda Petronski and the bullying she experiences by a group of middle class white girls.9 The novel has never been out of print since its publication in 1944, and continues to be “used in classrooms from elementary through high school” (Silvey). Most importantly, for the purposes of this analysis, it was reissued in 2004 during the mean girl boom in children’s and young adult literature. The Hundred Dresses prefigures key elements of contemporary mean girl scripts and also offers a distinct comparison to later works. Maddie, a bystander, narrates the novel. Estes represents queen bee, Peggy as wealthy, white, and “pretty” (5). Each day best friends Maddie and Peggy wait for Wanda to “have fun with her” (9) and to play the dress game.

“Wanda,” Peggy would say in a most courteous manner, as though she were talking to Miss Mason or to the principal perhaps. “Wanda,” she’d say, giving one of her friends a nudge, “tell us. How many dresses did you say you had hanging in your closet?”

(12)

Wanda would reply that she had a hundred dresses and then describe the fabrics and colors of her imaginary dresses. The girls laugh at her, knowing that Wanda only owns the one blue dress.

Maddie describes Peggy, and rationalizes the teasing as Wanda’s fault:

Peggy was not really cruel. She protected small children from bullies. And she cried for hours if she saw an animal mistreated. If anybody had said to her, “Don’t you think that is a cruel way to treat Wanda?” she would have been very surprised. Cruel? What did the girl want to go and say she had a hundred dresses for? Anybody could tell that was a lie.

(16)

Of course, the bullying is less about the fibs that Wanda tells and more about her ethnic and socio-economic status that marks her as an outsider and sparks the girls’ teasing.

Throughout the text, Estes deals with the power dynamics between and among girls. For instance, Maddie decides that she’d like to stop picking on Wanda, and begins to compose a note, but reconsiders because she doesn’t want to become a target.

Peggy might ask her where she got the dress she had on, and Maddie would have to say that it was one of Peggy’s old ones that Maddie’s mother had tried to disguise with new trimmings so that no one in Room 13 would recognize it.

(35)

Estes highlights how Maddie’s motivations don’t stem from an inherent mean girl gene, but rather from the threat of exposure, and shame about her own poverty.

Class 13 holds a drawing and color contest, and when students arrive to class the day of the competition they find that Wanda has drawn one hundred pictures of one hundred dresses. In Slobodkin’s illustration, dresses in different colors and styles cover the entire classroom, the wall behind the teacher’s desk as well as the windowsill. Wanda wins the prize, but cannot claim it because she has transferred schools. The teacher, Miss Mason, reads a note from Wanda’s father to the class: “Now we move away to big city. No more holler Polack. No more ask why funny name. Plenty of funny names in the big city” (47).

The rest of the novel focuses on Maddie’s reckoning with her decision to stand silently by rather than stop the teasing. Peggy and Maddie attempt to apologize to Wanda, they go to her house in Boggins Heights, and write a letter. On the final page of the book, Maddie “blinked away the tears that came every time she thought of Wanda standing alone in that sunny spot in the school yard close to the wall, looking stolidly over at the group of laughing girls” (80). Slobodkin illustrates the girls in the abstract, allowing the viewer to project themselves onto the blurred image of the perpetrator, the bystanders, or the victim. Anita Silvey notes that, “Slobodkin draws a mere suggestion of the characters allowing readers to imagine other faces on them.” This visual tactic suggests the ubiquity of the situation, and how the bully or bystander might change roles depending on context and relationships. Estes attends to the intersecting oppressions of class and ethnicity that mark the new girl as an outsider. Additionally, The Hundred Dresses foreshadows representations of the schoolgirl as either a vulnerable, morally superior victim or a potentially redeemable mean girl. For instance, in the end, Wanda serves as the embodiment of goodness. She sends a letter to Miss Mason and in it she writes: “I’d like that girl Peggy to have the drawing of the green dress with the red trimming ...