1

Setting the Scene: Local Economic Development in Southern Africa

Etienne Nel and Christian M. Rogerson

Context and Rationale

In recent years the concept and development strategy of Local Economic Development (LED) has gained widespread acceptance around the world as a locality-based response to the challenges posed by globalization, devolution, and local-level opportunities and crises (Glasmeier, 2000). In addition to locality-based actions and initiatives, at a higher level, LED support is now firmly on the agenda of many national governments and key international agencies, such as the World Bank (2001,2002) and the OECD (2003) which have endorsed its role in urban development and business promotion. Internationally, LED currently finds expression in a variety of forms, including aggressive place promotion, endogenous development, urban entrepreneurialism and community-based interventions, all of which have become hallmarks of locality based economic strategies over the last twenty years around the world. LED tends to manifests itself either as direct, community-based, pro-poor interventions and/or as pro-market endeavours to participate in a neo-liberal, global market. The assertion of local initiative has helped create and reinforce the bi-polar logic of “localism and globalism” as being hallmarks of contemporary society, economy, and politics (Hambleton et al., 2002). Within this context, issues of local leadership, the emergence of local champions, social capital, and the importance of partnership formation emerge as critical elements in the promotion of the “local” as an emerging arena for development action, leadership, and intervention.

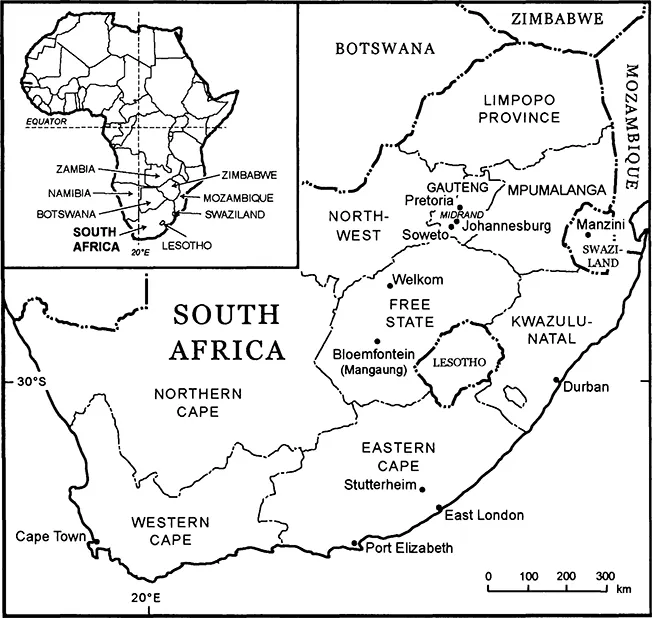

In the global context of research on LED, the case of southern Africa (figure 1.1) is of particular interest. Although there has been a recent trickle of writings, the amount of scholarly research on LED in the South is still relatively limited (see e.g., Ferguson, 1992; Zaaijer and Sara, 1993; Rogerson, 1995; Meyer-Stamer, 1999; Helmsing, 2001a, 2001b; Rodriguez-Pose et al. 2001; Helmsing, 2003; Van der Loop and Abraham, 2003) especially as compared to the extensive documentation on the South African LED experience. Indeed, within the developing world, much attention currently is being accorded to the LED experience in post-apartheid South Africa as a laboratory for experimentation, innovation and learning. LED emerged in South Africa as one of the more significant post-apartheid development options which is now being pursued by significantly empowered localities with the overt encouragement of national government. The post–1994 period has been one of the most dramatic in South Africa’s history. The country has had to grapple with an oppressive, apartheid-induced legacy, and, simultaneously respond to the challenges of neo-liberalism and globalization. Within this context the national state has recognised local governments as key agents of change and specifically tasked them to respond to the developmental needs faced in their localities, with a specific focus on the poorest members of society (RSA, 1998). In parallel with this essentially welfarist approach, the country’s embrace of neo-liberalism has also encouraged greater levels of local economic action and entrepreneurialism on the part of the private sector and by certain local governments responding to perceived market opportunities. This dual nature of LED is both a strength and a weakness. It is a strength in the sense that both pro-growth and pro-poor interventions should occur in harmony and a weakness owing to the widely differing opinions which exist on the application of the strategy, what its goals should be and how it might be applied. Central government draft LED policy papers suggests at a welfarist slant, as does current thinking in many local governments. Nevertheless, applied reality in the country’s larger centres, such as Johannesburg, clearly reflects the dominance of the growth-orientation and the partial marginalization of pro-poor interventions (Rogerson, 2003a).

At a broader level within southern Africa, a range of issues, not dissimilar to those taking place in South Africa, are playing themselves out. Debilitating conditions of poverty, the adoption of structural adjustment programmes, the increasing dominance of neo-liberalism and democratization parallel the widespread decentralization of decision-making powers to local level decisionmakers (UNCDF, 2002; UN-HABITAT, 2002; Conyers, 2003; Olowu, 2003; Smoke, 2003). Decentralization has become a hallmark of civic administration in most southern African countries, presenting local leaders with the challenge to find innovative ways to respond to poverty, to encourage development, to provide infrastructure and to facilitate growth. Whilst preliminary results in both South and southern Africa are mixed (and it is still early days), it is apparent that a new era of decentralized decision-making and local level autonomy and development action has dawned (Nel, 2000, 2002a). As yet, the results of this process are not easily predictable; initial findings suggest that LED does not promise to radically alter the status quo.

It is within the context of both increasing international recognition of the role and place of LED and the de facto recognition of the increasing significance of LED across the Southern Africa region that this volume had its genesis. Although LED does not enjoy the high profile attention which concepts such as globalization or national level decision making enjoy, none the less it is becoming a reality on the ground as local authorities, NGOs and the private sector throughout the region struggle to come to terms with newly devolved powers, rapid economic change, not infrequent economic marginalization, welfare needs and emerging economic opportunities. As the chapters in this book reveal, the picture is clearly not a uniform one. Localities across the region of southern Africa are adopting a wide range of strategies with varying degrees of success. Moreover, results at the national level suggest that serious obstacles still exist. Despite this suggestion, the widespread incidence of the phenomenon of LED serves as motivation and justification for this publication. In this introductory chapter, the concept and definition of LED will be unpacked before proceeding to an examination of the evolving policy context of LED, a discussion of key debates regarding LED and an outline of certain key trends that are emerging in the Southern African context.

The Scope of Local Economic Development

The economic endeavours of localities and local agents in Southern Africa, with or without external support, broadly fits within the theoretical context of what is understood internationally as locality-based economic development, or is more usually referred to as LED in the literature. In terms of understanding the scope of LED, Zaaijer and Sara (1993, p.129) state that LED “is essentially a process in which local governments and/or community based groups manage their existing resources and enter into partnership arrangements with the private sector, or with each other, to create new jobs and stimulate economic activity in an economic area.” More recently, according to the World Bank (2001, p.1): “LED is the process by which public, business and non-governmental sector partners work collectively to create better conditions for economic growth and employment generation. The aim is to improve the quality of life for all.” In a subsequent World Bank document it was asserted that “LED is about local people working together to achieve sustainable economic growth that brings economic benefits and quality of life to all in the community. ‘Community’ here is defined as a city, town, metropolitan area, or sub national region’” (World Bank, 2002, p.1). These quotations clearly identify the core focus of LED, emphasising the concepts of partnership, economic sustainability, job creation and improvement of well-being, taking place at the local or community level.

In recent years, Local Economic Development (LED) has been recognized, internationally, as a key response to the synergistic interplay of a variety of key forces that characterize the contemporary era. Among these trends the most important are the following:

the increasing decentralization of power and decision-making to the local level, which parallels the reduction in the role of the central state in the economy in a neo-liberal era;

globalization forces, which in an era of the diminishing importance of the nation state, compel a local-level response, to economic marginalization and/or opportunities which globalization presents;

economic change within localities, varying from de-industrialization to local innovation which requires local leadership initiative, response and direction; and,

the dubious results often achieved by macro-level planning and regional development interventions historically (Nel, 1994, 2001; Jessop, 2000; Helmsing, 2001a, 2003).

Overall, it is important to acknowledge that these trends are not unique to any part of the world, not least to the context of Africa situated on the global economic periphery (Helmsing, 2001a, 2003). Though occurring at different rates, the effects of globalization, of global economic crises and of the prominence accorded to the notions of enhanced democratization and devolution cumulatively have helped to ensure that local economic initiatives and self-reliance are a discernable trend throughout the world. As the pace of globalization accelerates, the rise of LED activity emerges as an integral part of a new wider emphasis upon local responsibility and power and on the democratization of daily life (UNCDF, 2002; Smoke, 2003). In the Southern African context, historical racially based inequalities, both socially and spatially serve as an additional motivation for locally appropriate interventions.

Generally speaking, the goals of LED tend to revolve around a set of common issues of job creation, empowerment, the pursuit of economic growth, community development, the restoration of economic vitality and diversification in areas subject to recession, and also of establishing the “locality” as a vibrant, sustainable economic entity, often within a global context (World Bank, 2001). A key theme which is disclosed in comparative international research, is that whilst the goals of LED strategies applied in different parts of the world might share certain similarities, different emphases occur, particularly between pro-business and pro-poor variants of LED. In the South or developing world it has been observed that poverty alleviation is a significantly more vital policy focus and research issue on LED agendas than in the context of Western Europe or North America (Rogerson, 2003a). Indeed, whilst LED or broader City Development Strategies in the North focus on issues such as responses to globalization, entrepreneurial and human capital interventions, business support and property-led development (Clarke and Gaile, 1998; Vidler, 1999), in the South Helmsing (2001a, 2001b) stresses that the focus of LED tends to be more on issues relating to community-based development, business development and locality development.

Local Economic Development in Post-Apartheid South Africa

The policy and practice of LED has become remarkably well established in South Africa in recent years. The first scholarly writings on LED in the country began to appear from the early 1990s (Claassen, 1991; Nel, 1994; Rogerson, 1994a, 1994b; Tomlinson, 1994). Starting from the limited cases of applied LED in both large cities and many small towns in the early 1990s, rapidly accelerating through the activities of the “forum” movement of the 1990s, the concept of community or locality-based development was implicit in the 1994 Reconstruction and Development Programme, the anchor framework for national post-apartheid planning (Tomlinson, 1994; Urban Foundation, 1994). Further institutionalization of LED occurred as its practice was effectively enshrined in the 1996 Constitution, in terms of a recognition of the “developmental role” of local government (Nel, 2001). Thereafter, LED in South Africa has been supported by a range of other policy and legal measures. Applied LED has evolved apace, such that by the beginning of the twenty-first century, all major urban centres in South Africa had established or were in the process of establishing LED Units or Economic Development Departments, whilst a range of NGO, community and private sector led initiatives have also emerged (Rogerson, 2000). In the remainder of this section, evolving LED policy in South Africa is reviewed before moving on to discuss current practice in the country.

The Policy Context

As noted above, the 1994 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) document made implicit references to the notion of LED through overt support for community-based development and locality based initiatives (ANC, 1994). In 1996 the national Constitution (RSA, 1996) local governments were mandated to pursue economic and social development. This concept was taken significantly further in 1998 when the Local Government White Paper was released (RSA, 1998). This document introduced the notion of “developmental local government,” which is defined as “local government committed to working with citizens and groups within the community to find sustainable ways to meet their social, economic, and material needs and improve the quality of their lives” (RSA, 1996, p. 17). In addition, local government is required to take a leadership role, involving and empowering citizens and stakeholder groups in the development process, to build social capital and to generate a sense of common purpose in finding local solutions for sustainability. Local municipalities thus have a crucial role to play both as policymakers and as institutions of local democracy, and are urged to become more strategic, visionary, and ultimately influential in the way they operate. In this context, the key thrust of such development strategies in post-apartheid South Africa is that, according to the minister for provincial and local government: “The very essence of developmental local government is being able to confront the dual nature of our cities and towns, and to deal with the consequences of the location of the poor in dormitory townships furthest away from economic opportunities and urban infrastructure. The solutions to these problems are complex and protracted” (Mufamadi, 2001, p.3). As Rogerson (2000, p. 405) comments, “In terms of the mandate of developmental local government the establishment of pro-poor local development strategies is therefore critical and central for sustainable urban development as a whole, particularly in dealing with the apartheid legacy of widespread poverty.”

The statutory principles for operationalising these concepts of developmental local government are contained in the 2000 Municipal Systems Act (RSA, 2000). A critical feature of this Act is the notion of promoting so-termed “Integrated Development Planning” within which LED is regarded as a key element (Harrison, 2001). Overall, in South Africa Integrated Development Planning has been defined as “A participatory approach to integrate economic, sectoral, spatial, social, institutional, environmental and fiscal strategies in order to support the optimal allocation of scarce resources between sectors and geographical areas and across the population in a manner that provides sustainable growth, equity and the empowerment of the poor and the marginalized” (DPLG, 2000, p.15). In essence, according to the Department of Provincial and Local Government, the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) is, “conceived as a tool to assist municipalities in achieving their developmental mandates” (DPLG, 2000, p.21), and as a planning and implementation instrument to bring together the various functions and development objectives of municipalities. Future government funding allocations to local governments (theoretically) are to be determined by the nature of plan...