![]()

Part I

Concepts and methods

![]()

1 Some critical thoughts on researching the quality of democracy

Philippe C. Schmitter

Introduction

The quality of democracy (QoD) has become the flavor of the year or perhaps of the decade among students of democracy—and not just among those studying new democracies. The suspicion has arisen and spread that, while it is manifestly the case that more and more polities around the world have the institutions of liberal, constitutional, electoral, representative democracy, in more and more of these cases (old as well as new) their respective democracies are not meeting the expectations of their citizens. The gap between what democracy promises them and what it delivers seems to be widening. Hence, political scientists have been competing among themselves to find negative and diminutive qualifiers—e.g., delegative, defective, flawed, façade, pseudo-, partial-, semi-, ersatz-, stalled-, low intensity, hybrid, illiberal—they can place in front of the term “democracy,” that serve to undervalue the status and accomplishments of both “real-existing democracies (REDs)” and “newly-existing democracies” (NEDs).

This widespread academic exercise presumes two things: (1) the presence of valid evidence of citizen dissatisfaction with their performance and (2) the existence of valid standards for measuring the quality of these democracies. Only if the first is true, would it be worthwhile spending much effort on conceptualizing and researching the second.

As for item (1), the evidence is considerable. Random surveys of public opinion in both REDs and NEDs routinely “discover” that an increasing proportion of respondents do not think that their vote counts, or that their rulers are paying attention to them. Most dramatic has been the decline in trust in core democratic institutions: elected politicians, political parties, and legislatures. But these same surveys often show that the decline also affects non-elected authorities: military, police, public administration, even scientists and physicians. Skepticism, in other words, has become a general characteristic of better-educated and informed publics—even if it tends to be focused on the political process.1 Interestingly, these surveys also tell us that interest in politics and the sense that politics affects one’s life-world has been stable or even increasing. So, the gap exists, but so does the awareness of it and the desire, presumably, to narrow it.

On the more quantitative side, scholars have observed a litany of “morbidity symptoms” to illustrate the extent of decline in a large number of both NEDs and REDs. At the top of it, one usually finds declining levels of electoral participation and party membership or identification, and a rise in electoral volatility and problems in forming stable governments. Previously dominant centrist parties find their ideologies are no longer credible to the public and are losing vote share to newly emerging marginal ones on the far (and usually populist) Right or Left. Parliaments have become less central to the decision-making process, having been displaced by greater concentration of executive power and a more important role for so-called “guardian institutions” dominated by (allegedly) independent experts. Governing cabinets have more and more members who have not or never been elected and who have often been chosen for their “supra-party” affiliations. Membership in and conformity to class-based intermediaries—trade unions and employers’ associations—has declined and this has negatively affected the influence of the former. Meanwhile, large firms, especially financial ones, have increased their direct access to the highest circles of decision-making. It should come as no surprise that income inequality in REDs has increased at a rate not seen since mass enfranchisement occurred in the late 19th Century.

As far as the “usual suspects” are concerned, there exists a rather similar consensus about the generic causes of crisis and decline. At the top, one almost always finds globalization since it has supposedly deprived the national state of the autonomy it previously enjoyed in order to be effective and responsive to the demands of its citizens. Multi-national enterprises, international financial institutions and, at least in Europe, multi-layered regional governance arrangements have imposed a complex mixture of constraints and opportunities that greatly limit economic and social policy agendas and the capacity to regulate and tax capitalists and their firms. Changes in the structure of production have weakened the collective consciousness of workers and undermined the class cleavage that had long provided the basis for Left and Right political parties. Changes in sectoral composition have vastly increased the importance of financial institutions that hire few (and very well-paid) employees that have little or no interest in collective action. Politics has become a full-time profession, rather than a part-time affair. Most of those who enter it expect to spend their entire careers there—and they surround themselves with other professionals: speech writers, media consultants, pollsters, “spin-doctors” and so forth. Citizens become increasingly aware that their representatives and rulers live in a different and self-referential world. Voting preferences have shifted from class, sector, and professional interests to a more individualistic basis related to issues of personal life style, religious/ethical conviction and the personality of candidates.

If that were not enough, citizens have become better educated and more skeptical about the motives and behavior of their politicians. And they increasingly can access much more independent (and critical) sources of information on the internet. Also, enormous flows of South–North migration have affected the very demographic composition of the population of most REDs, such that substantial proportions of residents in them have no citizen rights or prospects for gaining them. This cultural diversity has undermined perceptions of living in a common demos with a shared fate and, hence, a mutually acceptable sense of the public good. Pace the current populist resistance to this phenomenon in Europe and the US, REDs in the future will have accommodate to such diversity and build it into their reformed institutions.

More conjunctural factors have also allegedly played an important role. First and foremost, the collapse of Soviet-style “People’s Democracy” deprived Western REDs of one of their primary bases of legitimacy, namely, their manifest superiority over their Eastern rivals. Henceforth, REDs have had to satisfy the more demanding criteria of equality, access, participation, and freedom promised by democratic ideals. The wave of democratizations that began in 1974 also contributed to a general rise in expectations and unrealistic assertions about “the End of History.” Neo-liberal reforms failed to produce their promise of continuous growth, fair distribution, and automatic equilibration—leading by 2008 to the Great Recession which many REDs (especially in Europe) proved incapable of mitigating, much less resolving quickly.

At the core of this consensus about crisis in QoD lies the heavy reliance that the practice of RED and NED places upon representation—especially representation by means of political parties that compete regularly and fairly in elections within territorial constituencies that are expected to produce—directly or indirectly—a set of legitimate rulers.2 Admittedly, parties have never been “loved” by citizens partly because they are an overt expression of the interest and ideological cleavages that divide them, but also because there is ample reason to suspect—vide Roberto Michels—that they are unusually susceptible to oligarchy and prone to self-serving corruption (Michels 1962).3

None of this should be surprising since all REDs are condemned to be defective. Old democracies and new democracies may have their own specific deficiencies, but both are based on complex historical compromises with such rival orders as monarchism, socialism, nationalism, imperialism and, most of all, capitalism. They are “mixed regimes” with many non-democratic components that are bound to frustrate some of the expectations of some of their citizens, and they rely heavily on circumscribed and indirect mechanisms, not the least of which is that of representation. They are all, in other words, works in progress moving in dubious directions that fail to live up to the potential embedded in democracy’s core semantic notion of “rule by the people.” At best, they are based on “rule by politicians” who claim to represent their interests and ideals and who are ultimately accountable to them.

Even so, there seems to be little or no doubt that contemporary democracies—old as well as new—have many more disgruntled and alienated citizens than in the past (not to mention, the even more disgruntled and alienated foreign denizens that live among them and are deprived of democratic rights).4 Public opinion surveys during the past decade or so, as we have noted, tend to reflect this—although the proportion of those still answering “yes” to the question: “Is democracy is the best regime for your country” remains consistently high. So, item (1) is satisfied; now, let us pass to item (2).

The grounds for academic intrusion

Faced with this evidence from the actors themselves, why should academics bother with agonizing (and inconclusive) discussions about how to define and measure the QoD?5 The answer would seem to be simple: just let citizens decide for themselves what they think the relevant criteria should be and ask them in public opinion polls what they think about the QoD in their country.6 There are three good reasons why this may be insufficient:

1 Respondents may be incapable of distinguishing between the performance of the government in power and the nature and effect of the regime that brings these rulers to power and presumably affects (but does not completely determine) their behavior.

2 Respondents may only be aware of the political institutions that exist in their country (and that usually call themselves democratic) and, hence, be incapable of imagining how a different configuration of these institutions might improve the QoD.

3 Respondents in mass surveys are typically induced to respond to immediate events and to express opinions with regard to them, but are much less capable of reflecting on the relation between these stimuli and more deeply embedded values that will eventually structure their expectations concerning democracy.

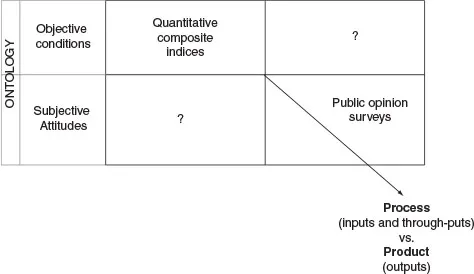

There is, therefore, considerable room for the intrusion of academic specialists into the debate about QoD, which is not to say that the literature in recent years that has examined it does not need some redirection. In Figure 1.1, I have made an effort to categorize the approaches that have been adopted.

Figure 1.1 Approaches to quality of democracy.

On the horizontal (epistemological) dimension, we find those scholars on the left who assert that evidence for the QoD should be gathered according to universalistic criteria. All democracies—old and new—should be judged by the same generic principles.7 This presumes that all citizens want and expect the same behavior from their rulers—regardless of where they are located, how long they have been democratic, what cultural norms prevail or what level of development they have attained. On the right side are those who are more sensitive to discriminating temporal, spatial, material, and normative factors that are likely to affect citizen expectations and, hence, the need to rely on relativistic criteria. This distinction is cross-tabulated by an ontological one, i.e., whether the process of assessment can be captured by objective indicators independent of actor perceptions or subjective ones articulated by respondents. The vast bulk of research on QoD can be found in the upper left and lower right cells—although there have been a few cases of “mixed method” research.8 The former consists of a vast effort to collect aggregate data that “audits” and quantifies performance according to universalistic principles postulated by (liberal or social) democratic theory; the latter relies on public opinion data gleaned from random mass surveys that leaves the specification of principles to the citizens of specific countries (and, hence, is compatible with a pluralistic conception of what RED should accomplish).9

Without denigrating what has been accomplished by both approaches, I propose to explore the empty cells in Figure 1.1: (1) the one that combines universalistic and subjective ...