Working Posture Assessment

The TACOS (Time-Based Assessment Computerized Strategy) Method

- 213 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Working Posture Assessment

The TACOS (Time-Based Assessment Computerized Strategy) Method

About this book

This book covers how to analyze awkward working postures, particularly of the spine and lower limbs, in specific groups exposed. The methods covered suggests how to evaluate the postures correctly, taking account of the duration and sequence of the tasks involved, even in very complex scenarios where workers are involved with multiple tasks and work cycles varying from day to day. Excel spreadsheets located on the authors' website (www.epmresearch.org) have been developed to gather, condense, and automatically process the data. The tools serve to implement the strategy for calculating risk associated with exposure to awkward postures, i.e. the TACOS method. Included are 5 case studies which include physiotherapists, workers from construction, archaeological digs, vineyards, and kindergarten teachers.

Features

- Provides a coherent definition of what the study of awkward postures is

- Clarifies and explains which parameters need to be detected and analyzed for the study of the working postures

- Defines the phases of a proper organizational study (e.g. tasks, postures, duration, and how often the postures will last) in the working cycle

- Presents a new and original risk calculation model for awkward postures, with particular attention to the study of the spine and the lower limbs

- Offers a free excel spreadsheet located on the authors' website which implements the strategy for calculating risk associated with exposure to awkward postures

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction and Aim

Contents

- 1.1 Meaning of “Postural Tolerability”

- 1.2 Remarks on Spinal Posture Studies Based on Biomechanical Methods

- 1.3 Analyzing the Tolerability of Working Postures for the Spine When Performing Manual Lifting Tasks, and for the Upper Limbs When Performing Repetitive Movements and/or Manual Lifting: Specific ISO Standards

- 1.4 Analyzing Spinal and Lower Limb Postures: The Aim of This Book

1.1 Meaning of “Postural Tolerability”

- cause discomfort in the short term;

- cause musculoskeletal disorders or diseases in the long term.

- a relatively large number of variables making up a posture;

- the virtually infinite number of postural combinations;

- the nonspecific nature of diseases and disorders related to awkward postures.

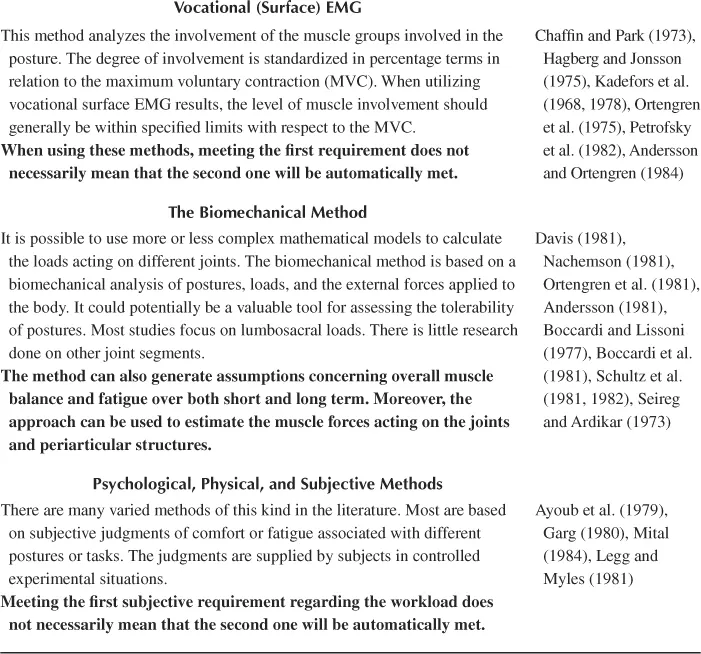

- electromyograms;

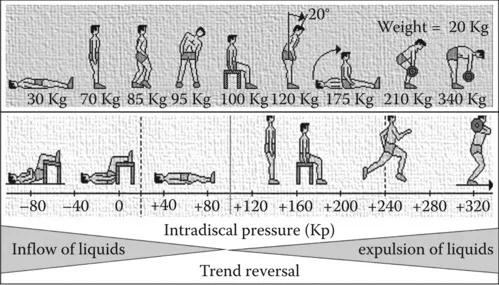

- direct and indirect intervertebral disc pressure measurements;

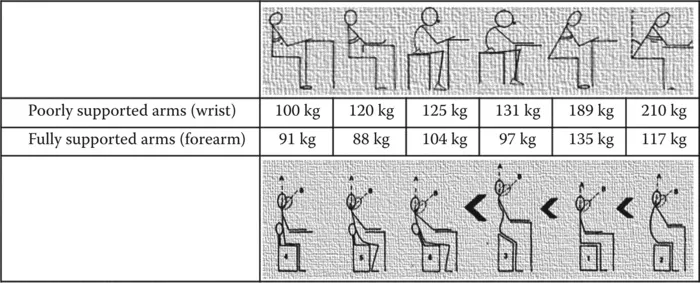

- the biomechanics of posture;

- posture acceptability from the psychophysical standpoint.

1.2 Remarks on Spinal Posture Studies Based on Biomechanical Methods

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Editors

- Contributors

- List of Contributors

- 1 Introduction and Aim

- 2 Methods for Evaluating Working Postures in International Standards: ISO 11226 (2000)—Evaluation of Static Working Postures and EN 1005-4 (2005)—Evaluation of Working Postures and Movements in Relation to Machinery

- 3 Working Posture Assessment Criteria and Principal Methods Reported in the Literature: A Comparison

- 4 The TACOs Method

- 5 Timed Score Calculation Methods in Multitask Exposure Scenarios

- 6 Simple Tools for Using the TACOs Method to Assess Postures: An Example of a Multitask Job in a Daily Cycle

- 7 Simple Tools for Using the TACOs Method to Assess Postures: An Example of a Multitask Job in a Weekly/Monthly Cycle

- 8 Simple Tools for Using the TACOs Method to Assess Postures: An Example of a Multitask Job in an Annual Cycle

- 9 The Physiotherapist: Example of an Analysis of Biomechanical Overload of the Upper Limbs and Awkward Postures of the Spine and Lower Limbs among Professionals in an Orthopedic Clinic

- 10 The Construction Worker: Example of Biomechanical Overload of the Upper Limbs and Awkward Postures of the Spine and Lower Limbs in Several Typical Tasks

- 11 Multitask Analysis among Workers at Archaeological Digs

- 12 Analysis of Back and Lower Limb Postures among Childcare Center Staff

- 13 Biomechanical Overload and Awkward Postures among Vineyard Workers: Risk Analysis

- 14 Conclusions

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app