Chapter 1

The gendered subject in the social world

In Western culture, a non-normative gendered life – such as a transgendered or transsexual life – is seen by many, even by the individuals themselves, as problematic, morally bankrupt or sick. Terms such as transsexual or transgendered carry so much stigma (Goffman 1963; Douglas 1966; Kando 1973; Leonard et al. 2012) that most who could be so labelled go to extraordinary lengths to avoid this labelling. Their life strategies often include bordering (Anzaldua 1987) behaviour; navigating the different identities and codes required in the various communities they move in, sometimes secretly passing (Kroeger 2003) as gendernormative and at other times being transgressive (Douglas 1966) and asserting their individuality. Those who don’t question normative beliefs on gender might seek a cure or medical intervention to eliminate their sense of non-normativity. There is a need to counter the lack of knowledge and understanding of people who do not or cannot conform to our cultural norms of gender performance. Better knowledge and understanding of the range of gender nonconformities will help both gender-nonconformist and gender-conformist individuals live more productive lives. My conviction comes from growing up feeling I was unable to meet the gender-specific social behaviours expected of me. And even though I do not identify as such, I have been ‘diagnosed’ by some in the medical profession as transsexual or as suffering from ‘Gender Identity Disorder’ (GID) (APA 1994).

I see this work as feminist in the sense that, at its core, it is a critique of patriarchy and male privilege, my perception of incompetent male hegemony, as well as challenging patriarchally endorsed normative gender coercion. This work is post-transsexual (Stone 1991) in that it relies on the autoethnographic subject (myself) to forgo passing (Kroeger 2003), which then enables me to write myself into feminist discourses on the trans experience.

As a child I felt incredibly alone, believing I was the only boy in the world who wanted to be a girl. Not long after puberty, I was depressed, disintegrating and suicidal. The coercion to conform to socially ascribed dichotomous gender roles led me to see two lose-lose options: either ignore my deepest feelings, or live as a girl and be ostracised and stigmatised. It took me many decades to realise I could challenge cultural gendernormative coercion, along with its social relations of subordination and domination, and engage in a non-normative subjectivity. In my early 20s, I discovered there were other people who might be a bit ‘like me’. But they were too far removed from my reality for me to be able to identify with them. Nor could I see myself reflected in any published transsexual biographies such as ‘Conundrum’ (Morris 1974) or April Ashley’s Odyssey (Fallowell & Ashley 1982).

By the 1990s, I had largely worked through my internalised negativity and found a way of being true to myself while living healthily in society. At that time, I socialised with like-minded people, and we were able to help each other by sharing our stories and insights. But as we found ways of living productive lives, our stories were seldom told. I then started to document and do presentations on my own story as a resource for others unhappy with their socially assigned genders, as well as to inform gendernormative health professionals, workmates, the media, university students and other community groups who were trying to understand gender nonconformity. However, I soon realised I was limited by the small numbers of people I could meet and the difficulty in addressing the complexity of the subject in a short conversation or a tutorial. I considered writing an autobiography, but came to believe I could have a deeper and broader reach by adding a rigorous analysis – solidly rooted in the social sciences – of my life story and how I reacted to the cultural influences attempting to coerce me toward gendernormativity.

Research themes and structure of the work

In a general sense, this monograph examines how I, the autoethnographic subject, have gained some understanding of the limits that culture has over my performance of gender and challenged the normative coercion to perform gender dichotomously as determined by my biology and consequently delivered myself a liveable life (Butler 2004). In this research monograph, I focus on three themes, which progress from the specific via the social to the consideration of social change. First, it asks what we can learn from the choices, successes and failures of our gender nonconforming autoethnographic subject (myself) in finding an empowered accommodation to the gender-dichotomous social world I have inhabited and so explicate themes around health promotion and education. In order to place this life in context, it is also important to explore how the individual was subjected to lifelong dichotomous heteronormative gender coercion from family, media, popular culture and other gender-rigid cultural texts. Second, it asks if we can shed light on and critique the normative operation of gender in society (Kando 1973, p. 137) and its tolerance for nonconformity by examining the interaction of our nonconforming subject with their social world. And third, following on from the previous themes – the subject’s life arc and the operation of gender in the social world – this monograph will be a testament to the need for remaking the gendernormative and heteronormative social worlds in terms of developing strategies for enhancing public health, social justice and equity. Note there is significant overlap – as well as contestations and confluences – between these themes of inquiry. The choice of constructivist research themes and qualitative methods means this research is not intended to answer any questions relating to the biological determination of gender.

The structure of this research monograph is designed to give a detailed analysis of the themes discussed in the previous paragraphs. I devote Chapter 2 to the critical framing of gender, primarily in terms of the sociology of gender overall and the sociology of trans and gender diversity. Chapters 3–5 present the autoethnographic data set in its social context, as well as providing initial levels of commentary. Chapters 6–8 address each of the primary research themes. Chapter 9 concludes by abstracting and synthesising the themes and noting important areas for further research. Over the rest of this chapter, I give an overview of my research methods, ethical considerations and how I have structured my data, analysis and conclusions.

Methodological overview

In this section, I discuss the reasons I believe phenomenological autoethnography is the most appropriate methodology for this project as well as discussing the criteria for exemplary work.

There have been many strategies advocated for use in qualitative research. Creswell (2009) focuses on five: ethnography, grounded theory, case studies, phenomenological research and narrative research. Autoethnography (Ellis 1999, 2013; Holman Jones & Adams 2010, Holman Jones et al. 2013) combines all five of these but is primarily an ethnography of the self or one’s own group, which includes a critical analysis of the narrative. It is also phenomenological in the sense that I, a participant (and also a case study), will describe the essence of my experiences of living in a gendered world when I was ill at ease with my culturally allocated gender. I will also use aspects of grounded theory in that I will derive general, abstract theory from the process of interacting in a gendered world, grounded in the participant view of the autoethnographic subject.

Storytelling is an essential tool in ethnographic research. Alain de Botton (2014) sees a major problem with contemporary news: its obsessive focus on the particulars of an event rather than on the hidden universals, “the psychological, social and political themes that transcend the stories’ temporal and geographical setting” (p. 90). He notes that modern audiences find Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar far more emotionally and morally engaging than the particulars of most current-day news stories. He suggests we could address universals embedded in news stories using the techniques of art. I definitely want my research to move beyond the particulars of my life and address universal themes. The processes of art in which I am most skilled, and which are most readily expressed on the printed page, are prose, poetry and visuals. First-person narrative, stream of consciousness and soliloquy are techniques I believe will be useful in the data chapters. Kiberd (2009) notes that James Joyce’s Ulysses is told primarily through his narrator Leopold Bloom’s inner voice, his stream of consciousness, his self-conscious awareness of himself in the world. And having read it, I feel I know Bloom much better than I know most of my friends and colleagues. Denzin (2014) sees a growing consensus for an evocative ‘literary aesthetic’ in autoethnography, “works that are engaging and nuanced, texts that allow readers to feel…a story that stays with the reader after she or he has read it” (p. 74). He emphasises the need for a method that goes “beyond sociological naturalism, beyond positivistic commitments to tell objective story” (p. 82). On conventional autobiography, I found Fox (2004) valuable: “a good autobiographer is writing an ethnography of his [sic] own life, and he [sic] should treat his [sic] task with the proper detachment and regard for the facts” (p. 47). Both the advantage and disadvantage of autobiography is insider knowledge, which can be used to give honest deep insight or to hide or distort the truth, either deliberately or through self-delusion.

I see the starting point as the collection of unabstracted data. The aim of phenomenology is to describe the temporal flow of what is experienced by the consciousness of the subject and to describe those phenomena free from any theoretical abstractions. On phenomenology, Kando (1973) notes, “Objectivity, here, means the accurate rendering of the subject’s subjectivity” (p. 133). Solomon (2000) adds, “there is no separating consciousness from the world. Consciousness in the world or of the world is a unified phenomenon” (p. B.109). Flynn (2006, p. 20) describes phenomenology as an iterative process which allows us to get closer to the essence of the conscious experience as we gather more information.

Data structured around liminal events, as gender projects

In overview, I use life story, cultural texts, poetry, photography and prose to examine and critique the interplay between gender nonconformity and normative cultural forces that impacted on my life. I will give examples showing that when an opportunity disappeared or my perception of my social environment evolved, I tenaciously looked for novel openings, opportunities and strategies for living in the world.

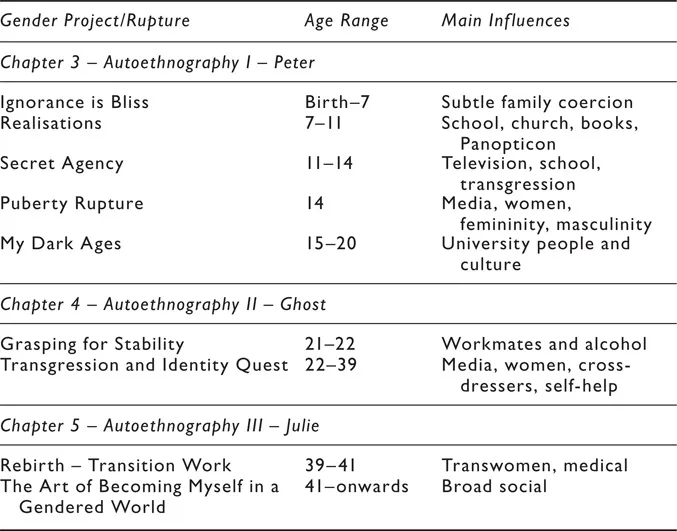

The data will be presented in chronological order, where turning points in my life story correlate with changes in gender performance and psychological health. Each liminal event or turning point, then, defines an era of stability, or what a playwright might call an act. These acts define the structure of the data. In this context, each of these acts can be considered a new “gender project” (p. 101), as described by Connell (2009). Connell, re-envisaging Jean-Paul Sartre’s ‘projects’, suggests that we can see gender learning, over a lifetime, as the creation of a series of gender projects in which people strategically develop improvised and creative interactions with both the social constraints and the possibilities of the local gender order. The autoethnography shows that in each era/gender project, which I have evocatively named, I did gender in a different way, reacting to the constraints and possibilities of my situation at the time. Table 1.1 summarises my listing of the liminal divisions/gender projects/ruptures of the autoethnographic data as well as showing how they are divided into three data chapters.

On exemplary autoethnography

When I told Professor Michael Bamberg, Clarke University (private conversation: 17 July 2009, Milé Cafe Bar, Melbourne) about my research, he said no one has yet achieved good autoethnography. He cited Arthur (‘Art’) Bochner’s (1997) It’s About Time and said that because his writing was ‘so good’ and so emotionally evocative, his students always ‘believed’ it and seemed totally incapable of criticising it. Bamberg went on to assert that no autoethnographer he has read has ever successfully achieved the insider/outsider balance. At that time, I determined I would use his criticisms to help me understand the criteria for, and then produce, good autoethnography.

Table 1.1 Autoethnography Overview

Bloor & Wood (2006) note that ethnographic authors have been criticised because they are usually outsiders and therefore cannot authoritatively represent the truth. Autoethnography by its very nature avoids this criticism. Reed-Danahay (1997) suggests that autoethnography has a double sense, “referring either to the ethnography of one’s own group or to autobiographical writing that has ethnographic interest” (p. 2). She notes that this dichotomy is in fact transcended because these two approaches are related, breaking down the distinctions between autobiography and ethnography as well as questioning the self/society split and the boundary between the objective and subjective. Referencing Goldschmidt, Reed-Danahay (2009) notes, “in a sense, all ethnography, is self-ethnography” (p. 29) because ethnographers write reflexively and use autobiography in their work. That is, the autoethnographer needs the dual/multiple and shifting identities of a boundary-crosser to enable the researcher to transcend the everyday in rewriting the self in the social world. As one who has experienced cultural displacement and multiple views of the world, Reed-Danahay’s view encourages me to believe autoethnography is suitable for this project. Holman Jones (2005) asserts autoethnography is a powerful tool for social, political and cultural change by bringing to life crises that engender rage that needs resolution, adding: “Rage is not enough…[the] challenge – to me, to you – is to move from rage to progressive political action, to theory and method that connect politics, pedagogy, and ethics to action in the world” (p. 767).

Spry (2001) suggests a number of criteria for effective autoethnograp...