![]()

Part 1

Hellenomanias from early modern to modernism

![]()

1

Modern stage design and Greek antiquity: Inigo Jones and his Greek models

Fiona Macintosh

There are numerous examples of the ways in which encounters with ancient Greek material culture have inspired innovation in modern scenic design and performance styles. Léon Bakst’s trips to Greece in the first decade of the twentieth century, which resulted in his now-iconic designs for the Ballets Russes’ Narcisse, L’après midi d’un faune and Daphnis and Chloé, fuelled a huge wave of Modernist energy devoted to the translation of ideas of Greekness onto the stage;1 and Nijinsky’s black-figure, profile dance movements against these designs in turn led to numerous dancing choruses that resembled animated Greek friezes.2 Equally transformative in terms of theatrical design were the sketches and objects brought back to northern Europe from the Grand Tour in the early seventeenth century, which laid the foundations for the experiments of the nineteenth-century stage historicists, such as those of J. R. Planché and Charles Kean.3

This chapter seeks to shed light on the earlier, less discussed Jacobean and Caroline period during which the trade in antiquities led to a huge burst in technological experimentation in scenic design. It focuses, above all, on the stage designs of Inigo Jones and their Greek models, which Jones encountered both in Italy on the Grand Tour and in the London house of his patron, Lord Arundel.

The unity of the arts in early modern England

From 1598, when George Chapman’s translations of Homer’s Iliad began to appear in print, until 1616, when his complete translations of both the Iliad and the Odyssey were published, there was a period of extraordinary creative energy and achievement in the English theatre. In many ways, Greek epic as mediated by Chapman informed the content and the form of the new drama. Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida (1602) and Thomas Heywood’s three plays, The Golden Age (1611), The Silver Age (1613), and The Brazen Age (1613), where Blind Homer appears in person, all look in various ways to Chapman’s translations.4 Chapman’s translation of the Odyssey, especially, unleashed generic innovation legitimising an alternative to comedy and tragedy in Shakespeare’s ‘Romance’ drama. Furthermore, the epic simile provided the dramatic soliloquy with new creative opportunities and exciting possibilities for examining and defining interiority and selfhood.5 The Court Masques in England from 1604–1640 equally benefited from this new source material and from the formal innovations they afforded.

Literary encounters with Greek antiquity were by no means separate from other creative engagements with the ancient world, at a time when voyages of discovery were opening up new realms of experience to both travellers and audiences at home. As Frances Yates argued many years ago, during this period it is important to speak of the ‘sister arts’ rather than literary texts in isolation.6 In Italy Homer was discovered in both text and art, from Petrarch’s acquisition of a Greek manuscript of Homer in the early 1350s to the publication of Niccolò della Valle’s Latin translation of the Iliad in 1510, which spawned numerous refigurations in literature and the visual arts.7 Chapman recognised the creative interdependence of the sister arts and he dedicated his translation of Musaeus (published in the same year as his complete Homer translations) to the architect and stage designer, Inigo Jones. Jones and Chapman were close friends and had collaborated a few years earlier, in 1613, on The Memorable Masque [for] … the Inns of Court (published in 1614). Chapman’s dedication fully acknowledges the breadth and depth of his friend’s knowledge of antiquity, singling out Jones, ‘especially for your most ingenuous (sic) Love to all Workes, in which ancient Greek Soules have appear’d to you’.8 For if Chapman’s translations of Homeric epics brought about exciting textual innovations in the theatre, Jones brought about equally significant and wide-ranging scenic innovations through his own translations of ancient Greek material culture into his stage designs.

The translations of the Homeric epics had ushered into the modern world immanent, though frequently absent, pagan gods, who occasionally arrived to resolve human crises. If the medieval period saw the Greco–Roman pantheon through a contemporary lens, with gods dressed as medieval monks, by the late fifteenth century the ancient gods resembled the Greco–Roman statues that were beginning to be excavated in Italy.9 Now in the English Masques at Court, where the pagan deities were invoked at critical junctures, complex machinery (as in the ancient theatre) was required to facilitate their entries and exits. But it wasn’t simply stage machinery that linked poetry and theatre architecture at this time; it was also, according to Chapman building on the Horatian paradigm ut architectura poesis, a pattern of form in both ancient poetry and ancient architecture, which Jones, ‘by whom Both are apprehended: and [by whom] their beames worthily measur’d and valew’d’.10

The sketches and objects brought back from southern Europe by Jones’s patron, ‘The Collector Earl’, Thomas Howard, Fourteenth Earl of Arundel, and by his entourage in the first few decades of the seventeenth century contributed significantly to a transformation in British architectural and scenic styles.11 They also contributed to the first modern realisation of that ancient theatrical synthesis of the arts—of scenery, words, music, and movement. It is often maintained that this unity of the arts was a distinctly eighteenth-century aspiration, only attempted in the modern world by the partnership of the composer, Christoph Willibald Gluck, and the choreographer, Jean-Georges Noverre, in the wake of the institutional division of the arts at the end of the seventeenth century.12 Through collaborations on the Masque, Jones, together with Chapman but predominantly with the poet/playwright Ben Jonson, produced a synthesis of the arts that Jones, in particular (as Chapman acknowledges in his dedication), had gleaned from a ‘love to all Workes, in which ancient Greek Soules [had] appeared to [him]’.

Jones and the early grand tour

After the relative isolation of England from wider European cultural developments in the late Elizabethan period, new opportunities for the understanding of a shared European inheritance emerged following the accession of James I of England (James VI of Scotland).13 The Treaty of London of 1604, which brought peace with Spain, meant that travel to southern Europe (especially Italy, which had been under Spanish viceroys and so out of bounds) was now possible. Early travellers were often, not surprisingly Catholic in sympathy if not in practice, and were prompted by a desire to compare European political and cultural practices.14 By 1605 Jones is referred to as a ‘great traveller’;15 and it is likely that he first went to continental Europe around 1598 or even earlier, and returned in 1609 as tutor and guide to the young Viscount Cranbourne on a tour of France, that took in the chateaux of the Loire Valley and the Roman sites at Nîmes and Orange.16

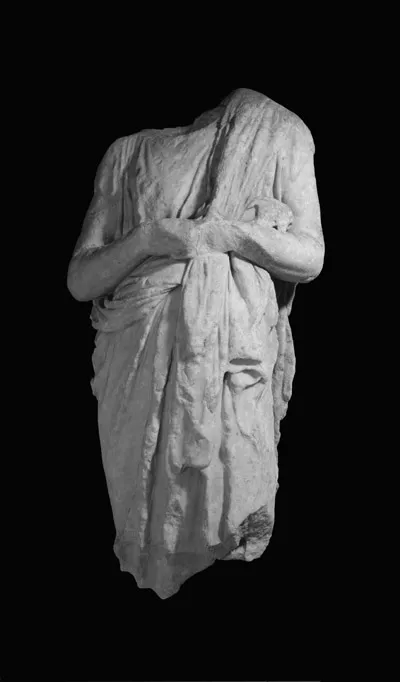

In 1613–1614 Jones enjoyed a lengthy period on the continent as a member of the entourage of his patron Arundel, mostly in Italy where they travelled as far south as Naples. It was during this trip that Arundel began seriously to collect antiquities, including probably the marble statue known as ‘Homerus’, which dates from sometime between the third and first centuries BC (Figure 1.1). It was during this trip that Arundel was also granted permission to excavate in Rome.17 As Guilding points out: ‘By building … authentic relics of the past into their lives … [the English aristocracy] appropriated their ancient authority and added to their own’.18

Arundel had a particularly urgent need to reconstitute his past, which had been sundered with the sequestration of his family estates by Elizabeth following his father’s imprisonment in the Tower of London as a Catholic rebel. It was not until the Collector Earl’s conversion to Protestantism in 1621 and his resumption of the title of Earl Marshal of England, signalled in Daniel Mytens’s painting (c.1618) by his baton (Figure 1.2), that he was able to buy back the family seat at Arundel.19 But from the first decade of the new century, Arundel, who had never met his father because he died in captivity in the Tower, was establishing himself as a patron of learning. As Henry Peacham wrote in The Compleat Gentleman (first edition 1622; second edition 1634), Arundel ‘transplant[ed] Olde Greeke in to England’ in Arundel House at the west end of the Strand in London.20

Figure 1.1 The Arundel ‘Homerus’

Figure 1.2 Thomas Howard, Fourteenth Earl of Arundel by Daniel Mytens (oil on canvas, c.1618) NPG 5292

Amongst the marble statues in the atrium in Arundel House, as painted by Mytens, it is possible to identify Homerus, Bacchus, Venus, and Eros.21 Peacham praises the marbles in Arundel’s collection not as ‘ideals’ (as Winckelmann would do a hundred years later) but because they bring the past to life so that the viewer has ‘the pleasure of seeing and conversing with these old heroes’.22 The ancient past here is no post-Romantic foreign country: instead it is immanent and informative at one and the same time. That the viewing of the marbles is of serious intent is borne out by Peacham’s observation of the Greek and Latin inscriptions:

You shall find all the walls of the house inlaid with them and speaking Greek and Latin to you. The garden especially will afford you the pleasure of a world of learned lectures of this kind.23

Almost immediately after the inscriptions arrived in London early in 1627, John Selden began to decipher them and to translate the Greek into Latin, which appeared shortly after as Marmora Arundeliana (1628).

‘The Collector Earl’ in the house Jones designed for him in the Strand in 1618 is understood to yoke past and present. By housing his collection of antiquities in a newly built atrium, Arundel deliberately linked his family history to that of antiquity. Mytens’s portrait of his wife Aletheia, daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury, who brought with her the fortune that allowed Arundel to amass his antiquities collection and restore his family estates, demonstrates the family’s links to Tudor history (Figure 1.3).24 Through the juxtaposition of ancient Graeco–Roman portraiture and Tudor portraiture, the Arundel/Howard line extends way back without rupture and now with restored pride.

From the 1620s onwards, with the help of his clergyman-turned-agent William Petty, Arundel started buying marble statues (he saw the value, unlike his contemporaries, of the fragment) and inscriptions from Asia Minor and the islands off the coast.25 As f...