![]()

p.21

Part I

From implicit to explicit knowledge

Typical development

![]()

p.23

1 “If you want to get ahead, get a theory”

Annette Karmiloff-Smith and Bärbel Inhelder

Introduction

How can we go about understanding children’s processes of discovery in action? Do we simply postulate that dynamic processes directly reflect underlying cognitive structures or should we seek the productive aspects of discovery in the interplay between the two? This is not an entirely new concern in the Genevan context since in the preface of The Growth of Logical Thinking (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958) it was announced rather prematurely that “. . . the specific problem of experimental induction analyzed from a functional standpoint (as distinguished from the present structural analysis) will be the subject of a special work by the first author”. Two decades have elapsed. With hindsight it is realized how much more experimentation and reflection were required to undertake the structural analysis. Operational structures are clearly an important part of the picture. They provide the necessary interpretative framework to infer the lower and upper limits of the concepts a child can bring to bear on a task. But they obviously do not suffice to explain all facets of cognitive behavior.

Our first experiments that focused directly on processes were undertaken as part of some recent work on learning (Inhelder, Sinclair & Bovet, 1974). The results illustrated not only the dynamics of interstage transitions but also the interaction between the child’s various subsystems belonging to different developmental levels. Though the learning experiments were process-oriented, they failed to answer all our questions (Cellérier, 1972; Inhelder, 1972). What still seemed to be lacking were experiments on children’s spontaneous organizing activity in goal-oriented tasks with relatively little intervention from the experimenter. The focus is not on success or failure per se but on the interplay between action sequences and children’s ‘theories-in-action’, i.e., the implicit ideas or changing modes of representation underlying the sequences. Although what happens in half an hour cannot be considered simply as a miniature version of what takes place developmentally, it is hoped that an analysis of the processes of microformation will later enable us to take a new look at macrodevelopment.

While not very typical of our current studies on goal-oriented behavior1 where the child needs to devise lengthy and complex action plans, the block-balancing experiment reported here has been selected as a first sample of the current work. Because of the fairly simple nature of this experimental task, a clearer initial picture could be drawn of the interplay between action sequences and theories-in-action.

p.24

Experimental procedure

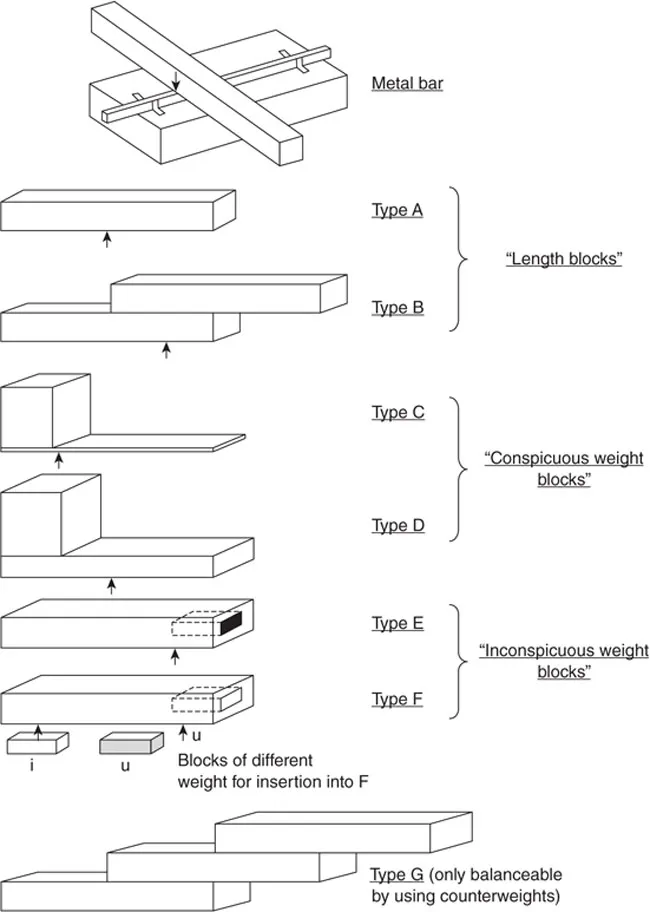

Subjects were requested to ‘balance so that they do not fall’ a variety of blocks across a narrow bar, i.e., a 1 × 25 cm metal rod fixed to a piece of wood. There were seven types of blocks, with several variants under each type. Some were made of wood, others of metal, some were 15 cm long, others 30 cm. One example of each type is illustrated in Figure 1.1. Type A blocks had their weight evenly distributed; B blocks consisted of two identical overlapping blocks glued together, weight being evenly distributed in each block. In A and B blocks, the center of gravity thus coincided with the geometric center of the length of the solid as a whole. We shall refer to A and B types as ‘length blocks’ since dividing the length in half gives the point of balance. The child can succeed without being aware that weight is involved. C types consisted of a block glued to a thin piece of plywood; D types were similar, except that the plywood was much thicker and thus the weight of the glued block had less effect. We shall call C and D types ‘conspicuous weight blocks’ since the asymmetrical distribution of the weight could readily be inferred. E blocks were invisibly weighted with metal inside one end, and F types had a cavity at one end into which small blocks of various weights could be inserted. E and F types will be referred to as ‘inconspicuous weight blocks’. An ‘impossible’ block (G type) was also used which could not be balanced without counterweights.

The experiment took place in two phases. In phase I, subjects were left free to choose the order in which they wished to balance each block separately on the bar. It was hoped in this way to gain insight into the ways in which children spontaneously endeavor to apprehend the various properties of the blocks: whether they group analogous blocks together, how they transfer successful action sequences from one block to another, and how they regulate their actions after success or failure. Once each block had been placed in equilibrium, children were requested to repeat certain items in a new order proposed by the experimenter. As an experimental precaution to make sure that no psychomotor difficulties would affect the results, subjects were first asked to balance two identical cylinders (2 cm diameter) one on top of the other.

When analyzing the results of phase I, it was hypothesized that children interpret the results of their actions on the blocks in two very different ways: either in terms of success or failure to balance the blocks which will be referred to as positive or negative action-response, or in terms of confirmation or refutation of a theory-in-action, which will be called positive or negative theory-response. A negative theory-response, for instance, implies contradiction of a theory either through failure to balance when the theory would predict success, or through successful balancing when the theory would predict failure. In other words, the same result was interpreted by children either as positive action-response or as negative theory-response and vice versa.

p.25

Phase II focused on this problem. About half of the phase I subjects in each age group were interviewed again some twelve months later. The purpose was twofold. First, to verify the cross-sectional analysis, the interpretative hypotheses we had made, as well as to determine the progress achieved by each subject. Secondly, since we now had a detailed description of the phase I developmental trends, we wanted to intervene rather more systematically in phase II by providing increased opportunity for positive and negative action- and theory-response, in order to study their interplay during the course of a session. Apart from balancing each of the blocks separately on the bar, subjects were also asked to leave one block in balance and try to balance in front of it on the same bar another block that looked similar but which had a strikingly different center of gravity (e.g., A types with E types), to add to blocks already in balance several small cubes of various size and weight, etc.

p.26

In both phases, a written protocol was taken by one observer and a continuous commentary was tape-recorded by a second observer on all the child’s actions, corrections, hesitations, long pauses, distractions, gross eye movements and verbal comments.2

Unlike many other problem-solving studies, tnis new series of experiments did not strive to keep tasks untainted by conceptual aspects. Indeed, we purposely chose situations in which physical, spatial or logical reasoning was involved but which we had already analyzed from a structural point of view, thus providing additional means for interpreting data. Both for constructing the material and interpreting results of the block-balancing task information was used from previous research (inter alia, Inhelder & Piaget, 1958; Vinh Bang, 1968; Piaget & Garcia, 1971; Piaget et al., 1973) about the underlying intellectual operations and children’s modes of interpreting weight and length problems.

The exact order of presentation of items and the types of problems set were not standardized in advance. Indeed, just as the child was constructing a theory-in-action in his endeavor to balance the blocks, so we, too, were making on-the-spot hypotheses about the child’s theories and providing opportunities for negative and positive responses in order to verify our own theories!

Population

Sixty-seven children between the ages of 4;6 and 9;5 years from a Geneva middle-class state school were interviewed individually.3 Phase I covered 44 subjects; 23 of these children were interviewed again in phase II. Five young subjects between 18 and 39 months were observed in provoked play sessions with the blocks.

In the results, some rough indications are given of the ages at which the various action sequences and theories-in-action are encountered, but this should not imply that the processes described are considered to be stage-bound. 22 subjects from this experiment were also asked to perform quite a different task, that of constructing toy railway circuits of varying shapes, and it was quite clear that children interpreting success or failure as theory-responses in one task might be interpreting success or failure as action-responses in the other task. Furthermore, similar action-sequences for block-balancing were encountered not only in many children of the same age but also during the course of a session with children of very different ages. On the basis of children’s verbal explanations of the relevant physical laws, the developmental trend falls into neat stages. If the analysis is based on children’s goal-oriented actions, this is not so obviously the case. However, both the nature and the order of action sequences as described in our results were overwhelmingly confirmed by changes during sessions as well as the longitudinal results of phase II.

p.27

Observational data

We felt it would be instructive to have an indication of how very small children go about balancing blocks. Accordingly, five subjects between 18 and 39 months were observed in provoked play sessions with our experimental material. This led us to interpret the older subjects’ seemingly anomalous behavior in conflict situations as rather clearcut regressions to earlier patterns. None of the five subjects failed in balancing the two cylinders used for checking psychomotor problems. As far as the experimental blocks were concerned, it was possible to coax the children into trying to balance a few blocks, but only for very short periods of time. Nevertheless, what they did was often organized. The following was the basic pattern: Place the block in physical contact with the bar at any point (e.g., extremities, center, pointed edge, side, etc.), let go, repeat. Their attention was frequently diverted to the noise made by the falling block; indeed, the two youngest subjects rapidly made their goal that of causing a loud noise. Gradually, with the first chance successes on the 15 cm “length blocks” (easier than the 30 cm ones), the three oldest subjects (32–39 months) lengthened their action sequences in a systematic way, as follows: Place the block at any point of physical contact with the bar, push hard with finger above that point of contact, let go, repeat immediately. However, these subjects did not move the block to another point of contact before letting go, although they had consistently done so when trying to balance the two cylinders or when building towers or houses with wooden cubes. It would appear that in such cases they were simply forming the parallel plane surfaces; in other words the problem of finding the appropriate point of contact between two objects of different shape did not arise. Nonetheless, even though the subjects placed the blocks at random points of contact, further development of action sequences by pushing on the block above the point of contact (i) seemed to denote that the need for spatio-physical contact had become clearer for the child, his finger acting somethat like a nail and thus simplifying the balancing problem and, (ii), provided the child with an indication through diffuse proprioceptive information of the fact that blocks have properties that counteract his actions.

The experimental material was in fact designed to allow for proprioceptive information. In previous research (e.g., Inhelder & Piaget, 1958; Vinh Bang, 1968) on equilibrium with a fixed fulcrum, subjects could only obtain visual information which then had to be expressed via another mode of representation.

Experimental data

Unlike previous Genevan research articles in which extensive quotations were given from what children said, this study’s protocols consist mainly of detailed descriptions of children’s actions. We shall, however, occasionally refer to children’s spontaneous comment when it is particularly illustrative. Here we will describe those action sequences that were encountered among most children of a given age and repeated several times by each child on the various blocks.

p.28

Many of the subjects in the experiment proper started the session in a similar way to the young subjects just described in the observational data. However, what seemed to take place developmentally between 18 and 39 months was observed during part of a single session among 4–6 year olds. Thus the initial approach was as follows: Place block at any point of contact, let go; this was immediately followed by a second attempt with the same block: Place at any point of contact, push hard above that point, let go. As the block kept on falling, the children gradually discovered through their act of pushing that the object had properties independent of their actions on it. Negative response sparked off a change from an action plan purely directed at the goal of balancing, to a subgoal of discovering the properties of the object in order to balance it. These children then undertook a very detailed exploration of each block trying one dimension after another, as follows: Place the block lengthwise, widthwise, upended one way, then the other and so forth. Such sequences were repeated several times with each block. Although the order of the dimensions tried out differed from one child to the next, each child’s exploration of the various dimensions became more and more systematic. Yet only one point of contact was tried for each dimension—for quite some time the children would never change the point of contact along any one dimension. Frequently, even when children were successful in balancing an item on one dimension (e.g., at the geometric center of length-blocks or along the length of the bar), they went on exploring the other dimensions of each block. It was as if their attention were momentarily diverted from their goal of balancing to what had started out as a subgoal, i.e., the search for means. One could ...