- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book analyzes the ways in which sport reflects, imitates, and questions cultural values. It examines the representation of team sports, heroes, race, families, and gender in films and other media. Analysis of the ways in which broadcast media and films create such images allows us to map the ways in which traditional cultural beliefs and practices resist and accommodate changes. Films about sport do not reproduce a simple, unified set of values-rather, they exhibit the complications of attempting to negotiate ideological contradictions. During the last 50 years, sports films have shifted from the heroic idealization of The Babe Ruth Story (1948) to films revealing complexities, controversies, and uncertainties within the sports world, like Everybody's All American (1988). These contradictions are especially strong in the areas of race and gender, which are related major changes in the traditional notion of the hero. The book traces the transformation of the image of the hero in sports films within the context of the development of the sports celebrity, epitomized by Michael Jordan.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hollywood's Vision of Team Sports by Deborah V. Tudor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

The Athlete as Hero, Star and Celebrity

The image of the professional team athlete exists at the intersection of several discourses. Modern heroism, stardom, celebrityhood, broadcasts of games, films, the institution of professional sports, journalism, sport and team history and the spectator's individual memory/fantasy formations all operate simultaneously to configure this image. In order to understand how these operations structure the idea of the "athlete," it is necessary to understand the social terms of its construction. As Richard Dyer writes in his Introduction to the book Stars, ". . . stars are part of the way film signifies (Dyer 1). It is as signifiers/significations that both fictional & real-life athletes can be examined. In this chapter I examine the multi-faceted construct "athlete-hero-star-celebrity." The analysis of three athletes' images treats them as texts, as defined in the introduction.

Athlete as Hero

In Western culture, the term "hero" possesses many nuances; however the field of mythological analysis provides a traditional idea of the hero and his actions within society. The mythological idea of the hero is so widespread that myth provides a primary area which defines the hero in Western culture. Definitions of these terms vary, but their perceived importance in studying Western culture persists. Nietzsche defines myth as "not merely the bearer of ideas and concepts but that it was also a way of thinking, a glass that mirrors to us the universe and ourselves (Travers 43). Robert Graves identifies myth as "grave records of ancient religious customs, events or ritual, and reliable enough as history once their language is understood"(ibid.). Graves' definition is interesting as it evokes the common dichotomy of myth and history only to eliminate it.

Joseph Campbell's work in the field of mythology provides a useful way to analyze the sports hero. The value of his model lies in its widespread presence within writings on Western athletics. Campbell's work on hero permeates much of the common discourse of heroes, and his terms, or closely related ones are frequently found in analyses of sports heroes.

Campbell's analysis identifies one prevalent method of defining the Western hero. His terms, whether used consciously or not, appear in many writings about sports. Academics, journalists, biographers, novelists and many essayists appropriate variations of his basic formulation of the hero, and this makes Campbell's model important. This is the way that people articulate the discourse of the athletic hero.

In Campbell's model, the hero's actions define him. A hero is one who ventures forth from the common world to a region of supernatural wonder. There he meets 'fabulous' forces and wins a decisive victory. The hero returns from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons upon his fellow man (Campbell 30).

The endurance of this form indicates a widespread attitude toward the hero originating in Western mythology: the perceived need for a hero of some sort, a (superhuman) man who can alter events and overcome threats to society and change history. The hope or wish for such a person derives from several social and psychological reasons: hopelessness against the inevitability of disasters, belief that "men make history," an escape from personal and political responsibility for shaping or participating in society.

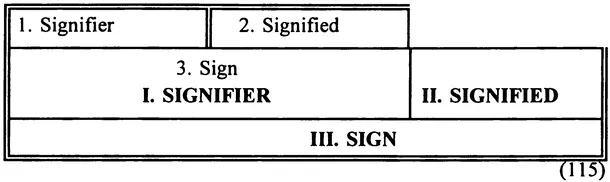

If Campbell's work gives us a good look at the type of hero commonly found in athletic discourse, the work of Roland Barthes provides a tool to examine the construction of such mythic systems. How do athletic texts create ideology as mythology? Barthes' system of the mythic is a "pure ideographic system where the forms are still motivated by the concept they represent while not yet by a long way covering the sum of possibilities for representation" (Mythologies 127). Myth is a form of speech (109) not a language but a language subjected to certain conditions. Barthes' myth resides within semiology but is also part of ideology. This is his model:

The first level sign (3) which exists as the relationship between signifier and signified becomes the second level signifier (III) in this operation. It is emptied of historical signification of the relationship it expressed at the level of language.

Barthes identifies an interesting transformation within the system. At level one the signified is "much poorer than the signifier." However at level two the site of mythological work, this reverses. The signifier is the form for the richness of the second level signified, a concept which richness appears through repetition in different forms. This is the crucial aspect of his work: instead of reading myths as a static, fixed tradition, it can be read as a dynamic process within which the "reader lives the myth as a story at once true and unreal"(128).

Following Barthes' model, the sites for enactment of myth reside wherever linguistic relationship exists for myth to use in its own creation. Myth-as-ideology can be unpacked from athlete-texts and film-texts in its various guises. Spectators "know" the athlete only as text. Mediation occurs even at live sporting events. The public address system's announcements about the game, and the players, the scoreboards information about other league contests (enhancing drama of pennant or division races) and replay on television screens at the stadiums all mediate the experience of the spectators at the stadium. Their expectations of the contest are formed as well by prior attendance and broadcasts of games. We know the athlete and the contest only through representation.

The link between the arenas of classical and mythological heroic activity and athletic activity still operate widely within our culture. Athletes are commonly perceived and described in heroic and mythological terms.

The connection between the hero's quest, outlined by Campbell, the athlete, and the formation of consciousness within Western culture is specified by Edward Edinger who views the tragic hero as an outgrowth of ancient Greek ritual drama and sacred games. In the Greek games, "wild and primitive energies are contained, channeled and finally transformed. . . ." Additionally, though, the athletes actions can be read as achieving "transpersonal meaning" through the dedication of the games to a god. Such activity serves what Edinger terms "evolution of consciousness." The connection of athletic activity to spiritual development continues with St. Paul, who uses athletic contests as "paradigms for spiritual development" (Edinger 68).

The quest structure also relates to Greek tragedy and the reenactment of the death and rebirth of the year-spirit . . . and that this ritual reenactment had four chief features: the agon, or contest, wherein the hero battles darkness or evil, the pathos or passion in which hero undergoes suffering and defeat, the threnos or lamentation for fallen hero and the theophany a rebirth of life on another level (67-68).

The idea of the heroic quest within the sports film is also identified by David Mosher as part of a "romantic impulse that is the essence of both sport and culture." The quest, he writes, is part of this impulse and serves to define ourselves. Sports films construct a narrative that reproduces the quest structure, with the resolution providing an "exaltation of the hero" (Mosher 16).

One element of Campbell's model applies readily to the way images of modern athletes are constructed and interpreted. Film and print biographies of athletes feature early childhood talents and accomplishments that predict/foreshadow the child's heroism on the playing field as an adult. However, using Campbell's entire statement creates a problem of analysis. The most difficult problem with using this analysis of the hero is the concept of the supernatural. The mythological hero journeys through the everyday world to a "region of supernatural wonder." For this to work in an analysis of athletes, the playing field would have to be equated with this supernatural region. One way of solving this problem comes by replacing the supernatural with another region of wonder—the region of commercial/public success. Thus, modern athlete-heroes travel not through Tartarus or the Elysian fields but through the playing field, an area with dual significance; it is both the physical arena where the game (job) is played and the region of public knowledge where the hero's actions are received and read. An athlete-hero performs his feats before the public eye and these feats are not limited to home runs, passes completed, but also include, for example, the amount of salary earned. This off-field accomplishment figures heavily in the public's perception of an athlete's success.

A second reconfiguration of the supernatural region is possible. The playing field is always within culture, yet separated from other cultural "fields", such as politics, by repeated overt denials of the presence of politics within sports, and by perceptions of the playing field as an entity embedded within an institution offering equal opportunity for minority players.

One final characteristic of Campbell's model that functions within athletic representation is his notion that legends tend to support an idea of predestination of the hero. The hero usually possesses precocious strength or wisdom as a child (Campbell 319). The prodigious feats of athletes during their childhood years figure prominently in both fictional and non-fictional representations of athletes.

Writers working specifically on the mythology of sports view heroes as crucial figures within that system. Richard Crepeau identifies myth as a symbolic structure expressing moral and esthetic values, and heroes as figures embodying sports social mythology. Michael Real sees sporting events like the Super Bowl as a mythological activity which participates in the process of making "sacred the dominant tendencies of a culture, thereby sustaining social institutions and life-styles" (233). Its value arises from the fact that while it provides a "communal celebration of and indoctrination into specific socially dominant emotions, lifestyles and ideas," it also is perceived as a game (235), in Barthes' terms cited above, something at once "true and unreal."

The ways in which these mythological terms relate to each other and create meaning can be analyzed by examining ways in which certain discursive elements are paired, or bundled. Claude Levi-Strauss, in Structural Anthropology removes the study of kinship studies from the natural world into the world of images; he states that they exist "not in nature but in consciousness, an arbitrary system of representations." (50) Sports as a discourse also exists in and through a series of representations. Examining these representations helps us learn how our real lived lives become "mythologies."

Richard Lipsky links the worship of the sports-hero to the importance of winning, of success, in fact, to "any threat to moral and community values (Lipsky 103), In such "crisis" situations the hero's "courage disposes of the threat of humiliation and chaos and symbolizes the possibility of human control (ibid.).

The three authors cited above indicate the widespread representation of the sporting hero in Western culture which reiterates the type of heroic activity abstracted from mythologies by Joseph Campbell.

Athlete as Star

Athletic stardom has diverse meanings as well. The simplest measure of stardom would be performance, but this is inadequate as a model. It is, however, a strongly held belief about athletes as well as film stars (Dyer 18). A simple comparison of statistics shows that some players become big stars while actually providing less on field production than lesser-known players. To be a star, an athlete must be an outstanding player who receives media attention beyond the activities of the playing field. Market considerations therefore form an important aspect of stardom. An athletic star must perform in a good media market. Athletic stars and film stars do share some common social origins and uses. In common with film stars, the sports star is perceived as somehow unique. Richard Dyer states that the perception of this quality is central to the star phenomenon. Drawing on Bala Balazs' work on the closeup, he notes that spectators believe that these shots capture somehow the unique, unmediated personality of the performer (170) which is already present in the film. Sports broadcasts frequently use the closeup within a narrativized structure. These shots are employed at moments when the athlete's reaction to a stressful situation or a successfully completed play and signify within that context, the athlete's individuality. It is his individual contribution to the game that is stressed by the insertion of closeups. The use of closeups helps to create athlete-stars in a way similar to the creation of spectator readings of star-characters within classical hollywood films. The close-up shot within a sports broadcast allows a space for the spectator to believe that s/he observes a unique individual personality in effective action that somehow transforms his immediate temporal-spatial universe: the game and the field. This perception seems to prove the effectiveness of individual action in society and provides reassurance to the spectator that s/he too, can transform the world. This emphasis on individuality thus disguises the nature of historical social relations and substitutes an ideology of effective individual action. The belief that the image of the athlete embodies the Western notion of individuality relates to ways in which the film star is read. Stars embody a range of types, one of which is the "individual" (111).

Athletic stardom departs from Dyer's model for film stars due to differences in the relationship between what he calls "star and character" (99), He "conceptualizes a star's total image as distinct from a particular character he plays in a film." (ibid.) Athlete's "roles' cannot be assigned to the realm of the fictional, even though sports broadcasts assume one function of fiction, narrativizing the athlete's life and career. Unlike an actor playing a baseball player, a real life second baseman accumulates statistics that determine the conditions of his livelihood.

Athlete as Celebrity

The term celebrity helps form the text of the athlete as well. Star, hero, and celebrity overlap, but distinguishing elements exist. The term carries a connotation of "lightweight" value. Celebrities appear as ephemeral, consumable elements within the public media markets. Indeed, this dependence upon media to create celebrities appears as an essential part of the celebrity's makeup. James Monaco, in Celebrity, notes that celebrities are "passive objects of the media" (6). This statement implies that the celebrity does not actively create his/her place in the public spotlight; but depends upon media interest to create and sustain a condition of public knowledge. One phenomenon of celebrityhood is the use of celebrities as elements of media feedback loops, wherein news about a celebrity is reported. That is, the act of reporting a celebrity's activities in one source becomes an event worthy of reportage in a second source. For example, a local paper may report that someone receives coverage in this week's People magazine (14). While this activity occurs with regularity in the sports world as well as in other public fields, it does not indicate in itself that the term celebrity defines the athlete-star-hero. Athletes may be used as celebrities, circulating within the same media circuits, but they differ from celebrities in that they are known for some particular activity. Daniel Boorstin's oft-quoted phrase "celebrities are well-known for being well-known" (qtd. in Monaco 4) does not apply to the figure of the athlete. He does something; he performs on the playing field.

The off-field activities of athletes remain in the public sphere and provide a process in which athletes become celebrities, but this interest in off-field life proceeds from what they do on the playing field (Clarke and Clarke 72). Perhaps Boorstin's catchy phrase needs some inflection anyway. Even the most superficial celebrity's fame must be rooted in some activity, however mundane or brief. Hosting lavish parties or being married to a famous financier for many years is an activity. Celebrityhood seems to inflate the value of activities within the public arena, however, until the person who has done something at one time remains newsworthy for many years.

Certainly, the notion of success forms a crucial part of the quality of the athlete's stardom/celebrity/hero status. During the heyday of the Chicago Bears, the two years following their 1986 Super Bowl victory, a large number of players and coaches took advantage of their notoriety and obtained contracts with Chicago and sometimes national media. In 1987, the Bears "led the NFL with 30 radio and TV shows. The stars ranged from punky quarterback Jim McMahon. . . . to tight end Emery Moorehead" (Bierig).

The personal notoriety of Ex-Bear Jim McMahon has declined rapidly since he left the Bears in 1989. Since then, he has worked for the San Diego Chargers, the Philadelphia Eagles and now the Green Bay Packers as a backup quarterback. Some of the events in his life (e.g. birth of a child) still receive regional coverage, but only rarely does he receive national play. McMahon's celebrity status has lessened as his personal success diminishes; however, his reputation as a hero-star during the eighties remains intact, if increasingly distant.

Players of lesser stature or weaker statistics than McMahon, Sandberg or Jordan may achieve celebrity status during a part of their careers but as they exit the sporting world, their celebrity values drops. Exceptional star-heroes, like Reggie Jackson however, may draw crowds for years and may retain high name value. Reggie Jackson's continuing name value seems to be based on his longevity as a successful baseball player. He had many productive years, especially as a member of the Oakland As. Longevity, which is easier to attain in baseball, a less punishing sport than football, separates him from Jim McMahon, who was a good athlete but only enjoyed a few years of high quality play due to injuries.

When Jackson purchased a Chevy dealership in 1988, this event received national sports coverage. Jackson says he decided upon this particular car dealership because he's always believed in "baseball, hot dogs, apple pie and Chevrolet" (Spander 1). In this statement, Jackson refers to an old Chevy ad campaign that incorporates references to "All-American" qualities symbolized by links among cars, sports and foods. Jackson himself drives a Rolls-Royce and collects exotic cars (ibid.)

Jackson's reference to such an all-American pantheon of values and commodities covers over many contradictions of his career. He was an ardent individualist; he was actively, aggressively Black in a sport which still uses white pastoral terms of self-reference. However, Jackson's image still fits within the parameters of allowable images of the athletic world.

The film star, and the athlete-star both signify a range of ideological qualities that are important at distinct historical periods. Thus, the dominant type of at...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Original Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The Athlete as Hero, Star and Celebrity

- Chapter Two: Images of the Athletic Hero in Films

- Chapter Three: Gender, the Family and Sports

- Chapter Four: The Play of Race Within Sports Films

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index